Suffering has its limit, but fears are endless.

—Pliny the Younger, 108Petrified Forest

Fear, says Lewis Lapham, is America’s top-selling consumer product.

By Lewis H. Lapham

The Temptation of Saint Anthony (detail), by David Teniers the Younger, 1640–60. © Rijksmuseum.

Let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.

—Franklin D. Roosevelt

Great self-destruction follows upon unfounded fear.

—Ursula K. Le Guin

Speaking to citizens of what in 1933 was still a democratic republic, Roosevelt sought to strengthen the national resolve in the depth of the Great Depression, “preeminently the time,” he said in his first inaugural address, to tell “the whole truth, frankly and boldly,” no need to “shrink from honestly facing conditions in our country today.” His fellow countrymen took him at his word, and the national resolve proved strong enough to emerge from the Depression, in 1941–45 to win the war against Germany and Japan, in the years since to bring forth the wealthiest society and the most heavily armed nation-state known to the history of mankind.

Heroic resolve, but not heroic enough to surmount the innovative and entrepreneurial American genius for making something out of nothing and the equally innovative and entrepreneurial American genius for self-deception. The force of mind rooted in the soil of adversity didn’t take hold in the flower beds of prosperity; placed under the protective custody of the atomic bomb and sicklied o’er with the pale cast of money, the native hues of resolution lost the name of action.

Fear itself these days is America’s top-selling consumer product, available 24-7 as mobile app with color-coded pop-ups in all shades of the paranoid rainbow. Ready to hand at the touch of a screen, the turn of a phrase, the nudge of a tweet. Popularly priced at conveniently located checkpoints on drugstore and supermarket shelves, at airports and tanning salons. Diligently promoted by the news and fake news bringing minute-to-minute reports of America the Good and the Great threatened on all fronts by approaching apocalypse—rising seas and barbarian hordes, maniac loose in the White House, nuclear war on or just below the horizon. Our leading politicians and think-tank operatives shrink from both truth and falsehood, regard mental paralysis as the premium state of securitized being. Our schools and colleges provide safe spaces swept clean of alarming, unjustified speech, credit a rarefied awareness of nameless, unreasoning terror as evidence of superior sensibility and soul.

Not the outcome envisioned by Franklin Delano Roosevelt, but the one raising the question addressed in this issue of Lapham’s Quarterly. How does it happen that American society at the moment stands on constant terror alert? In no country anywhere in the history of the world has the majority of a population lived in circumstances as benign and well-lighted as those currently at home and at large within the borders of the United States of America. And yet, despite the bulk of reassuring evidence, a divided but democratically inclined body politic finds itself herded into the unifying lockdown imposed by the networked sum of its fears—sexual and racial, cultural, social, and economic, nuanced and naked, founded and unfounded. Why and wherefrom the trigger warnings, and whose innocence or interest are they meant to comfort, defend, and preserve? Who is afraid of whom or of what, and why do the trumpetings of doom keep rising in frequency and pitch?

Fear itself doesn’t need the publicity. The oldest and strongest of the human emotions, awakened in the embryo fighting for breath in the birth canal, fear is nature’s free gift to all its sentient creations. The author Caroline Alexander credits the ancient Greeks with having many words for fear—almost as many as the Inuit have words for snow—and this issue of Lapham’s Quarterly doesn’t lack for text and illustration of straightforward terror, nervous apprehension, panic that impels battle rout, shock that strikes dumb with amazement, horror that jabbers the teeth, trembles the limbs.

In my capacity as human being, I’ve met with most if not all of the descriptives handed down from antiquity, but in my profession as journalist, I’ve encountered primarily the distinctions between what Sigmund Freud in 1917 defines as real fear and neurotic fear, the former a rational and comprehensible response to the perception of clear and present danger, the latter “free-floating,” anxious expectation attachable to any something or nothing that catches the eye or the ear, floats the shadow on a wall or a wind in the trees. Real fear invites action, the decision to flee or fight dependent upon “our feeling of power over the outer world”; expectant fear induces states of paralysis, interprets every coincidence as evil omen, prophesizes the most terrible of possibilities, ascribes “a dreadful meaning to all uncertainty.”

I’m old enough to remember when Americans weren’t as easily persuaded to confuse the one with the other. In grammar school prior to the advent of the atomic bomb, I was taught that looking fear straight in the face was the root meaning of courage, told to learn from the example not only of Alexander the Great and Admiral Lord Nelson but also from the lives of Mahatma Gandhi and Abraham Lincoln. The curriculum was pre–World War I, the works of Julius Caesar, Joseph Conrad, and Rudyard Kipling as well as Theodore Roosevelt’s advice to first imagine being a fearless man and to then try to act like one. Further teachings of the old lesson appear in this issue in Philippe Petit’s essay and in the passage from Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon.

I was ten years old in August 1945 when Fat Man and Little Boy fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and although I didn’t know it at the time, not yet having read Freud or met Henry Kissinger, my further acquaintance with fear was for the most part to take the form of the neurotic. Fear of the unseen and the unknown was to be faced down in the bright and shining armor of American exceptionalism, the belief, instilled at birth if nowhere inscribed on parchment, that Americans are, by definition and divine right, true and kind and good. Less fortunate peoples of the earth commit monstrous crimes; Americans cleanse the world of its impurities. Their cause is always just; nothing is ever their fault.

So at least went the thinking of the newly enthroned masters of the universe in Washington accepting America’s victories in World War II as proof of its virtue. During the first half of the twentieth century, the European powers had twice attempted suicide, and in 1945 what was left of Western civilization was transferred into the American account. The continental United States hadn’t suffered the scourge of war, and it was easy enough for the heirs to the fortune to deem themselves singularly favored by both God and mammon. The country’s immense wealth assured the buying of a risk-free future (maybe, if the money was right, the chance of living forever), and for as long as America retained sole title to the atomic bomb, the fires of heaven were in clean and safe hands.

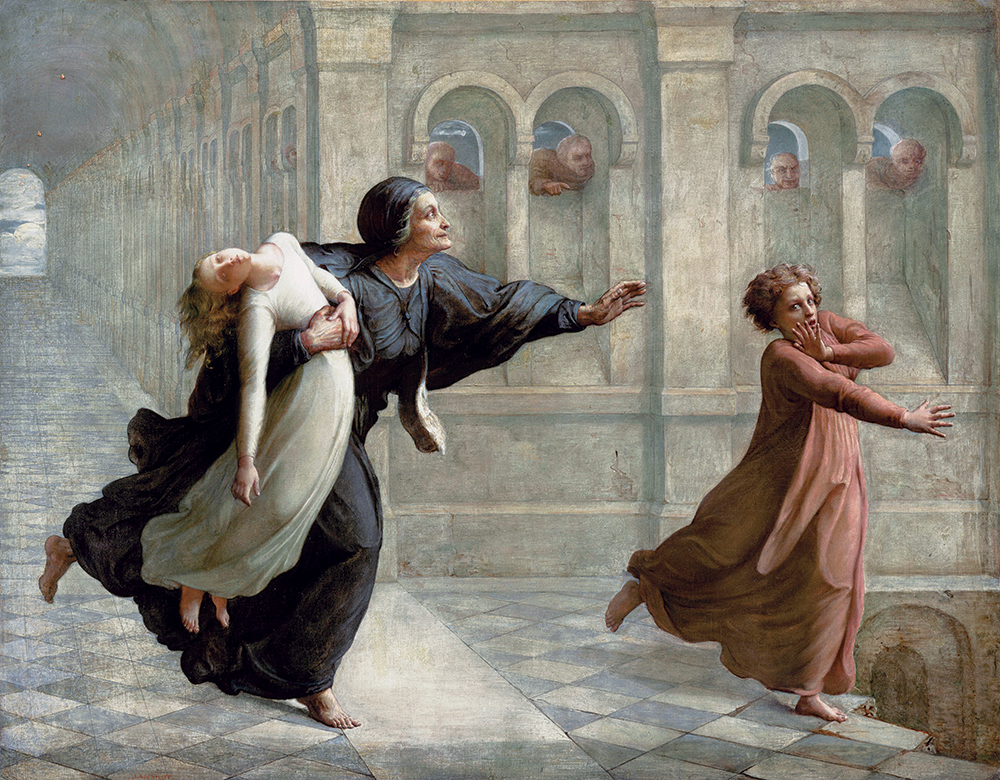

Nightmare, from the painting cycle The Poem of the Soul, by Louis Janmot, 1854. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

The period of grace expired in August 1949 when the Soviet Union successfully tested a pirated copy of the Fat Man bomb. From that day to this, the peoples of the earth have been held hostage to a religion founded on the gospel of extortion. The Cold War with the Russians produced the doctrine of mutual assured destruction, statesmen and generals on both sides of the iron curtain guaranteeing to kill everybody there if you kill everybody here; together we preserve humanity by agreeing to eliminate it. For the everybodies whose lives were the stake on the gaming table, the bargain didn’t leave much room for Teddy Roosevelt’s looking real fear straight in the face; people without a feeling of power over the outer world neither flee nor fight. The choice is to remain upright in the morally and spiritually perfect attitude of the innocent victim. The policy accorded with the modernist line of literary despair in undergraduate vogue during my years at Yale College in the post–atomic bomb 1950s—man a weak and pitiable creature standing no chance against “the system” (never defined but always malevolent), dreams of love and art doomed to be fetched up a creek or sold down a river.

Nor was there much room for acting the part of a fearless man in President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s construing of the Cold War (in 1953, in his first inaugural address) as the forces of good pitted against the forces of evil, “lightness against the dark,” American virtue surrounded on all fronts by incoming extinction.

Expectant anxiety maybe weakens the resolve of individual persons, but it strengthens the powers of church and state. Fear is the foundation of all government, the law, or the commandment that maintains peace on earth, the hold on property, goodwill toward men. Several contributors to this issue speak authoritatively to the point, among them the Greek dramatist Aeschylus in 458 BC; Niccolò Machiavelli, sixteenth-century courtier and historian; Thomas Hobbes; and Andrés Bernáldez.

Pillar of communities pagan and Christian, fascist, communist, and capitalist, the oldest and strongest human emotion is also the most wonder-working of all the world’s marketing tools. Used wisely, innovatively, and well, it sells everything in the store—the word of God and the wages of sin, the divorce papers and the marriage certificate, the face cream and the assault rifle, the grim headline news in the morning and the late-night laugh track.

As a street-side reporter for the New York Herald Tribune in the early 1960s, I could count on meeting real fear at the scenes of subway accident and building collapse, neurotic fear on a rewrite desk bent to the task of manufacturing evil omens and terrible possibilities. Briefly assigned to the Trib’s UN bureau in the spring of 1961, I was there with the first news of American marines wading ashore on the beaches of Fidel Castro’s communist Cuba. The intel was a premature garbling of the bungled invasion twenty-four hours later in the Bay of Pigs. The story appeared in the early edition sold on the street before midnight; it was corrected in time for final home delivery, and I was excused my enthusiasm because it followed at the direction of the paper’s senior UN correspondent, who in turn had been reliably informed by sources well below deck at the CIA and the Pentagon.

Reassigned to the rewrite desk in the city room on West Forty-First Street, I took calls from the paper’s foreign correspondents, and on an otherwise slow afternoon in 1962 our man in Moscow dictated a press release issued by the Russians announcing a significant advance in Soviet weapons technology. The dispatch deserved maybe four paragraphs on page seventeen, but John Denson, editor of the paper, happened to be passing by the desk as I was extracting the copy from the typewriter. Glancing briefly at the story in my hand, he tapped it lightly with the tip of his pencil.

“What you see there,” he said, “is the beginning of World War III.”

I said I didn’t doubt the fact, but I wasn’t sure I saw it clearly.

Denson scribbled down the name and phone number of a foreign-policy expert at Columbia University, told me to say it was John Denson who was asking for enlightenment. I can’t now say for certain who was the anonymous source at the other end of the phone; to the best of my knowledge and recollection it was Zbigniew Brzezinski, subsequently national security adviser to President Jimmy Carter but in 1962 still working toward an academic credential in the history and wealth of nations. I read him the dispatch, and he understood at once what Denson expected; for the next twenty minutes, with digressions to the treaties of Vienna and Brest-Litovsk, Zbig (or maybe not Zbig) parsed the text to mean that First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev’s initiatives in favor of détente had been declared inoperative by the militarists in the Politburo, that in a matter of months if not weeks Soviet tanks would be moving into Poland.

Siege of Baghdad (detail), miniature from a 1435–36 edition of The Book of Victory, by Sharaf ad-Din Ali Yazdi. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Louis V. Bell Fund, 1967.

Denson found the prospect pleasing. Expectant anxiety sells newspapers; a tribute to the innovative and entrepreneurial American genius for making something out of nothing. The story appeared the next morning on page one with a Moscow dateline, lengthened and thickened with opaque abstraction under an ambiguously ominous headline. The copy jumped to an inside page dressed with a stock photograph of Soviet armor on parade in Red Square.

The Cold War was born in the cradle of expectant anxiety; so were the wars in Vietnam and Iraq. The Soviet Union at the end of World War II possessed few or none of the intentions—invasion of Western Europe, communist world domination—ascribed to it by America’s diplomatic observers and intelligence agents in Moscow and Berlin. The terrible possibility was neurotic fear of the shadow on the wall. The Red Army had lost eleven million men in the war with Nazi Germany, its artillery drawn by horses; Russian industry was in shambles, the population not far from starvation.

The innovative and entrepreneurial consensus in Washington resurrected from the ruins the evil Soviet Empire—stupendous enemy, world-class and operatic, menace for all seasons, dread destroyer of American wealth and well-being. America was the light, Russia the oncoming darkness. The diplomat George Kennan stated the position in a memorandum circulated within the State Department in 1948.

We have about 50 percent of the world’s wealth but only 6.3 percent of its population…In this situation, we cannot fail to be the object of envy and resentment. Our real task in the coming period is to devise a pattern of relationships which will permit us to maintain this position of disparity without positive detriment to our national security. To do so, we will have to dispense with all sentimentality and daydreaming.

Kennan’s preferred patterns of relationship presupposed an American realpolitik strong-mindedly turned away from what he regarded as “unreal objectives such as human rights, the raising of the living standards, and democratization.” The interested parties in Washington (political, military, media, and economic) turned willingly to the task of replacing the antiquated American republic, modest in ambition and democratic in spirit, with a militant oligarchy obsessive in the concern for its own security, and the uses of expectant anxiety over the last seventy years have proved to be varied and many, the profit abundant and certain.

Fattened on the seed of openhanded military spending (upward of $15 trillion since 1950) the confederation of vested interest that President Eisenhower identified as the military-industrial complex brought forth an armed colossus the likes of which the world had never seen—weapons of every conceivable caliber and size, a vast armada of naval vessels, light and heavy aircraft, guidance systems as infallible as the pope, tracking devices blessed with the judgment of the recording angel. Powers once assigned to God passed into the hands of physicists and politicians; what had been divine became human, the idols of man’s own nuclear invention raised up to stand as both agent and symbol of the Day of Judgment.

The turbulent decade in the 1960s (the civil rights movement; antiwar protests; the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, and Martin Luther King Jr.) raised the force levels of the public alarm, merged the real fear running around loose in the streets (big-city race riots, student riots at venerable universities) with the neurotic fear always running around loose in the heads of the propertied classes. The always fearmongering news media projected armed revolution along the lines of the one that deposed and decapitated Louis XVI; the violent fantasy sold papers, boosted ratings, stimulated the demand for repressive surveillance and heavy law enforcement that blossomed into one of the country’s richest and most innovative growth industries.

Nothing is more despicable than respect based on fear.

—Albert Camus, 1940The tearing down of the Berlin Wall in 1989—as much of a shock and surprise to the director of the CIA as it was to the editors of the New York Times and National Review—undermined the threat presented by the evil Soviet Empire, and without the Cold War against the Russians, how then defend, honor, and protect the cash flow of the nation’s military-industrial complex pumping air and iron into the conspicuous consumptions of the American dream? A precious asset, the communist ogre in the totalitarian snow, and in 1989 not easy to replace. The Japanese couldn’t play the part because they were running short of money, the Colombian drug lords were too few and too well-connected in Miami, the Arab oil cartel was broke, and the Chinese were busy making shirts for Ralph Lauren.

The custodians of America’s conscience and bank balance found the solution in the war on drugs. Seeing no barbarians at the gates, they searched for monsters at home, ransacked the local newspapers for flaws in the American character. Surveillance satellites overhead Leipzig and Sevastopol were reassigned stations over metropolitan Detroit and the back lots of Hollywood movie studios, and within a matter of months the authorities looked for the usual suspects in the general categories of subversive behavior and opinion—black male adolescents, leftist English professors, aging hipsters, welfare mothers, homosexuals, performance artists, illegal immigrants, others too numerous to mention.

The stockpiling of domestic fear for all seasons (the instrument of power that no self-respecting military empire can afford to leave home without) is the political alchemist’s trick of changing lead into gold, the work undertaken in the 1990s by the presidential campaigns pitching their tents and slogans on the frontiers of race and class. The noun American lost all value unless preceded by an adjective signifying authentic proof of existence as black American, gay American, white American, female American, Native American, rich American, poor American, dead American. For every benign “us” the candidates find a malignant “them”; for every neighboring “we” (no matter how eccentric or small in number) a distant and devouring “they.” The strategies of division sell newspapers and summon votes; and to the man who would be king, the popular hatred of government matters less than the atmosphere of resentment in which the people fear and distrust one another.

Tell us your phobias and we will tell you what you are afraid of.

—Robert Benchley, 1935The destruction of Manhattan’s World Trade Center towers in September 2001 strengthened the American claim to the moral and spiritual perfection of the innocent victim. The Bush administration declared America attacked by all the world’s evil and took up arms against a figment of its imagination—Saddam Hussein’s nonexistent weapons of mass destruction. “We go forward,” said President George W. Bush, displaying the innovative and entrepreneurial genius for self-deception, “to defend freedom and all that is good and just in our world.”

Undertaken to prove the theorem of its world-dominating omnipotence, the war in Iraq has shown the American Goliath humiliated in defeat. Like the war on drugs, the war on terror is unwinnable because waged against an unknown enemy and an abstract noun. But while a work in progress, it is a war that returns a handsome profit to the manufacturers of cruise missiles and a reassuring increase of dictatorial power for a stupefied plutocracy that associates the phrase national security not with the health and well-being of the American people but with the protection of their private wealth and privilege. Unable to erect a secure perimeter around the life and landscape of a free society, the government departments of public safety solve the technical problem by seeing to it that society becomes less free.

The war on terror brought up to combat strength the nation’s ample reserves of xenophobic paranoia, the American people told to live in fear—suspect your neighbor and watch the sky; buy duct tape, avoid the Washington Monument, hide the children. Given enough time and trouble over the last sixteen years, their collective fear and loathing collected into the cesspool from which Donald J. Trump emerged, in January of 2017, to become the president of the United States.

Click here to listen to an audio version of this essay read by Lewis Lapham.