The cover of Collier's Weekly, October 31, 1903. British Library.

The old landmarks were all in their place. There were the chemical corner and the acid-stained, deal-topped table. There upon a shelf was the row of formidable scrap-books and books of reference which many of our fellow-citizens would have been so glad to burn. The diagrams, the violin-case, and the pipe rack—even the Persian slipper which contained the tobacco—all met my eyes as I glanced round me.

—Arthur Conan Doyle, “The Adventure of the Empty House,” 1903

No. 221B Baker Street is the most famous address in detective fiction. It is Sherlock Holmes’ heartland, a springboard to adventure and a recuperative haven, the scene of quizzical deductions and dramatic denouements, an experimental laboratory, a central hub for spies and messengers, and one of the intellectual centers of Europe. It appears in all four of the novels and most of the fifty-six stories that Arthur Conan Doyle wrote about Holmes and Watson.

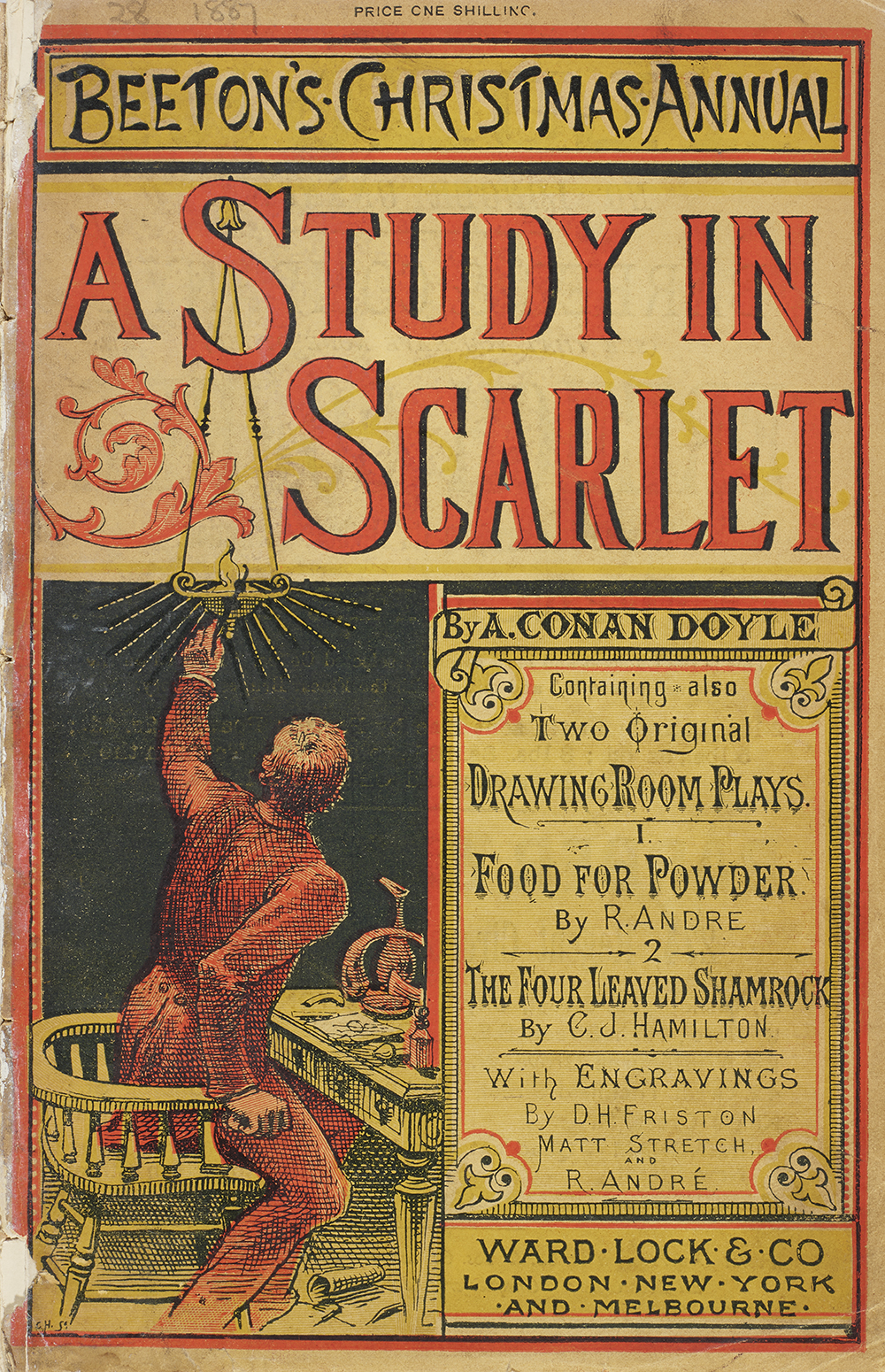

No. 221B’s topographical situation came early on in Doyle’s imagining of a brilliant “consulting detective,” as skilled in the art of deduction as was his own medical mentor in Edinburgh, Dr. Joseph Bell. Doyle’s original jottings for A Study in Scarlet (1887) refer to one “Ormond Sacker, from Soudan from Afghanistan,” living at “221B Upper Baker Street” with one “Sherrinford Holmes,” a “reserved, sleepy-eyed young man—philosopher—collector of Violins.” At the time, Doyle himself was living two kilometers east of Baker Street in Montague Place, near the British Museum. Choosing Baker Street, rather than one of the luxurious blocks of mansion flats that were springing up in London’s West End in the 1890s, was deliberate. It was respectable but unostentatious, a facade behind which Holmes could lurk discreetly. The gang of street urchins immortalized as the Baker Street Irregulars would not have been welcomed by upper-class neighbors. It was also conveniently placed for the Great North Road and the London railway terminals. Our heroes rarely spend much time in Baker Street once “the game’s afoot,” but it is usually the start and end point for the tales, and at times Holmes “would lie upon the sofa in the sitting-room, hardly uttering a word or moving a muscle from morning to night.” It is, writes scholar Robert Harbison, “one of the most distilled versions” of the Victorian sense of home. Holmes’ enclosure is exaggerated “because people are missing and ritual fills up every vacant space.”

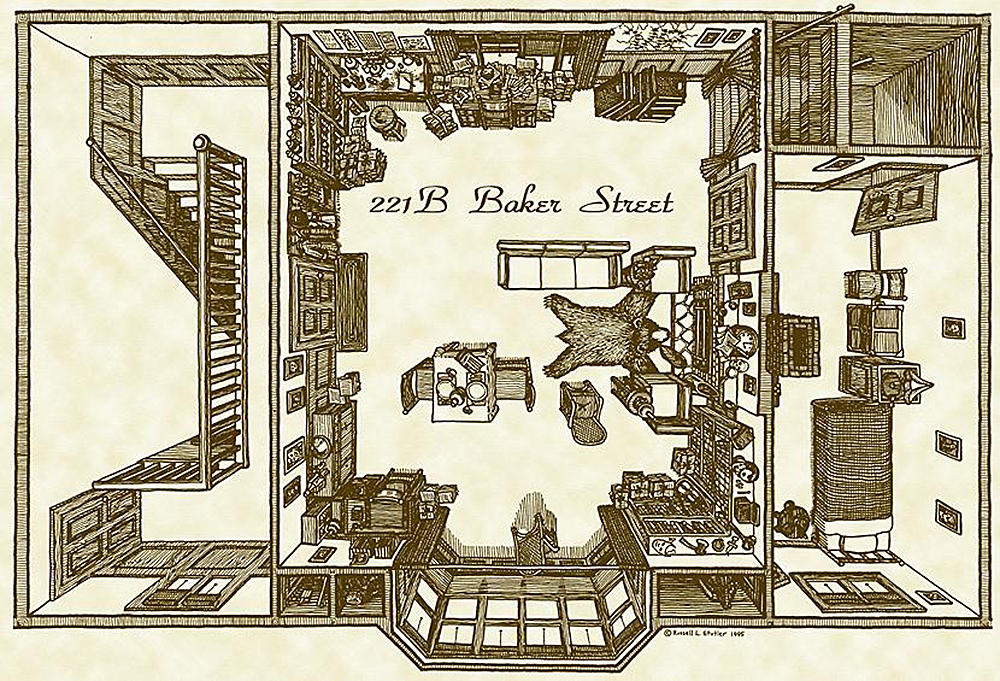

The layout of the lodgings is described in detail in the second chapter of A Study in Scarlet. Watson is invited by Holmes to inspect “a suite in Baker Street” that he has his eye on.

We met next day as he had arranged, and inspected the rooms at No. 221B, Baker Street, of which he had spoken at our meeting. They consisted of a couple of comfortable bedrooms and a single large airy sitting room, cheerfully furnished, and illuminated by two broad windows. He will have nothing but the tools which may help him in doing his work, but of these he has a large assortment, and all in the most perfect order.

The rooms are being let out by the discreet and respectable Mrs. Hudson, who manages the housekeeping with the help of a maid and a “buttons,” or pageboy. Clues to the contents of both sitting room and bedroom are liberally scattered through the novels and stories that Arthur Conan Doyle wrote between 1887 and 1927, when Holmes did at long last take his last bow.

There is a bathroom, unless Watson got Billy the page to bring up a tub in front of his bedroom fire so that he could have the bath he mentions taking in The Sign of the Four (1890). Mrs. Hudson and the maid cook in the basement and have bedrooms at the top of the house. In the spacious first-floor sitting room, armchairs flank the bearskin rug that lies in front of the fireplace, there is a wicker chair for visitors, tobacco is secreted in a Turkish slipper and cigars in the coal scuttle. On a deal table in one corner chemical equipment is to hand. Mention is also made of a closet for disguises, a jackknife stabbed through a pile of unanswered letters on the mantelpiece, a “gasogene” soda siphon, a Stradivarius violin, pipes of all shapes and sizes, and much else. All in all, it lives and breathes bachelor heaven.

Holmes’ decided preference for the single life and intolerance of any feminine fussing is confirmed in “The Reigate Squires” (1893), when he agrees to go to convalesce in Surrey only after Watson assures him that Colonel Hayter’s establishment “was a bachelor one.” Holmes also has a virtual retreat in his own mind. Defending his refusal to know anything about subjects he thought irrelevant, he likens a man’s brain to “a little empty attic.”

You have to stock it with such furniture as you choose. A fool takes in all the lumber of every sort that he comes across, so that the knowledge which might be useful to him gets crowded out, or at best is jumbled up with a lot of other things so that he has a difficulty in laying his hands upon it. Now the skillful workman is very careful indeed as to what he takes into his brain attic.

The adventure in which 221B earns its spurs as a heroic house, and in which it is described in most detail, is “The Empty House” (1903), the celebrated story which reveals that Holmes did not fall to his death with Moriarty at the Reichenbach Falls, as he seemed to do a decade earlier in “The Final Problem” (1893). Instead, after three years of living undercover, he reveals himself to Watson and takes him on a lengthy peregrination around London, ending up in the empty Compton House, opposite the rear of their old quarters. From its window, he shows Watson the setup he has staged in the sitting room of 221B: a silhouetted figure that shifts position occasionally appears to be Holmes himself, seated in a chair. Holmes has calculated that Moriarty’s second-in-command Colonel Moran will take the bait and shoot at him, and so he does, revealing his whereabouts. Once Moran is apprehended and packed off to prison, mouthing curses, Holmes and Watson (whose wife has conveniently died while Holmes was absent) take up their bachelor partnership once again:

Our old chambers had been left unchanged through the supervision of Mycroft Holmes and the immediate care of Mrs. Hudson. As I entered I saw, it is true, an unwonted tidiness, but the old landmarks were all in their place…There were two occupants of the room—one, Mrs. Hudson, who beamed upon us both as we entered—the other, the strange dummy which had played so important a part in the evening’s adventures. It was a wax-colored model of my friend, so admirably done that it was a perfect facsimile. It stood on a small pedestal table with an old dressing-gown of Holmes’ so draped round it that the illusion from the street was absolutely perfect.

Often, when the house is the hero of a book, its housekeeper is its essential interpreter and enabler. Mrs. Hudson, Holmes’ landlady as well as his housekeeper, is no exception. Behind the scenes at 221B, she orchestrates the household arrangements and meals. As time goes on, she is paid “a princely sum” to compensate for such untoward happenings as callers at all hours, occasional gunshots, a broken sitting-room window frame, the sacrifice of a sick terrier, and sudden invasions by street urchins. Not only does the house belong to her, she frequently plays an important part in the action: it is she who crawls in to shift the wax dummy of Holmes every fifteen minutes in “The Empty House.”

Doyle’s own domestic life could not have been more different from that of his bachelor hero. He liked the role of the classic Victorian paterfamilias, something that his father had never been. He married Louise “Touie” Hawkins in 1885, and remained loyal to her all her life, despite falling in love in 1897 with the charismatic Jean Leckie, whom he married a year after Touie’s death in 1907.

Doyle’s extended family included his own and his spouses’ brothers and sisters as well as five children, along with a motley mix of dogs, horses, and other pets. Closest to his heart was his mother Mary Foley Doyle, recipient of all his confidences by letter, but always refusing to live with him. In his medieval romance Sir Nigel, he painted her portrait as Dame Ermyntrude Loring, alongside his own as her son, Sir Nigel. In his childhood he admired her dogged resilience in face of his father Charles’ addiction to alcohol and drugs, and was relieved when after Charles’ death she found a protector in their lodger, Dr. Bryan Waller. Following Waller’s example in qualifying as a doctor seemed a sensible way to ensure a good income; he warmed up by taking a job as ship’s surgeon on a whaler, then set up his plate in Portsmouth, soon deciding to specialize in ophthalmology—a prescient move for the man who created the world’s most observant detective.

Maintaining a family home mattered to Doyle. He lived at various times in three substantial Edwardian houses. The first was 12 Tenison Road in Norwood (1891–94), where he and Touie took vigorous exercise on a tandem tricycle; he made Norwood the setting for The Sign of the Four and “The Adventure of the Norwood Builder.” The second, Undershaw (1897–1907), was built to his specifications at Hindhead in the Surrey hills, a climate that suited Touie’s consumptive tendency. Undershaw boasted a miniature monorail electric railway big enough for passengers in its garden and was rich in armorial stained glass: Doyle inherited his mother’s pride in her descent from the Plantagenets. His longest-lasting residence was Windlesham Manor, near Crowborough (1906–31), where he moved after his marriage to Jean. He also spent some time at Bignell Wood, near Minstead in the New Forest.

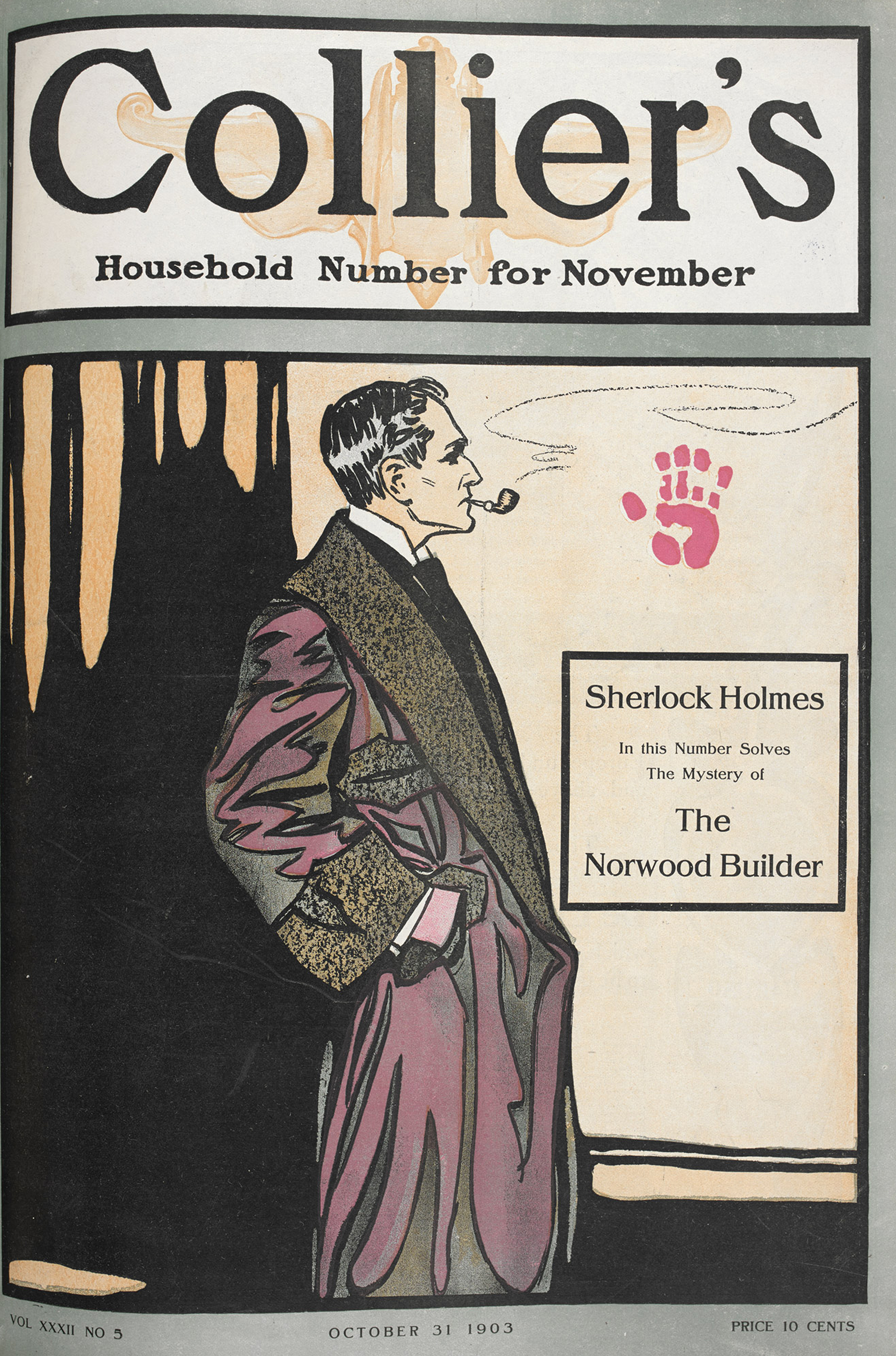

Despite the success of the Sherlock Holmes stories, Doyle himself did not rate them highly. Working on a second series of Holmes stories in 1891, he wrote to his mother on November 11 to say that he thought of “slaying Holmes in the sixth [story] & winding him up for good and all. He keeps me from better things.” The “better things” were his historical fictions Micah Clarke, The White Company, Brigadier Gerard, Rodney Stone, and Sir Nigel (“My absolute top!”). What kept Doyle writing about Holmes and Watson was the popular enthusiasm for their adventures that led magazine editors to raise their offers for Sherlock stories from £25 each to £1,000 for a dozen. In April 1893 Doyle did kill off Holmes, but he resurrected him ten years later because the American magazine Collier’s Weekly offered him the enormous sum of $25,000 for six stories and $45,000 for thirteen, regardless of length. “I don’t see why I should not have another go at them and earn three times as much money as I can by any other form of work,” he wrote to his mother in the spring of 1903. Like it or not, he had created a legend and an imaginary residence that has over the years acquired a vast speculative literature. Every step any Doyle character takes in or around Baker Street has been catalogued and questioned; every material object classified with mock scholarly precision. In 1940 real spies moved in. Either chance or an influential spook’s sense of humor set up the World War II Special Operations Executive in Baker Street, and Baker Street or Bakerstrasse remains espionage slang for an HQ.

It is a credit to the immediacy of Doyle’s writing that so many readers thought he was writing fact rather than fiction, and addressed countless letters to Holmes, in Baker Street, rather than to Doyle. Ironically, the entirely invented premises became established reality in 1951. When Doyle wrote A Study in Scarlet in 1897, Baker Street addresses ended at around 100; “221B” was deliberately nonexistent, as was 403 Brook Street in “The Resident Patient” and 427 Park Lane in “The Empty House.” But Sherlock Holmes’ lodgings fascinated the nation to such an extent that, as part of the celebrations for the Festival of Britain, “221B” was recreated in minute detail on an upper story of the Abbey National Building, which stretched across numbers 219–229 of the extended and renumbered Baker Street. A Daily Telegraph leader praised the staged apartment under the headline “Holmes, Sweet Holmes.”

Excerpted from Novel Houses: Twenty Famous Fictional Dwellings by Christina Hardyment, published by Bodleian Library Publishing. Copyright © 2019 by Christina Hardyment. Distributed in North America by the University of Chicago Press.