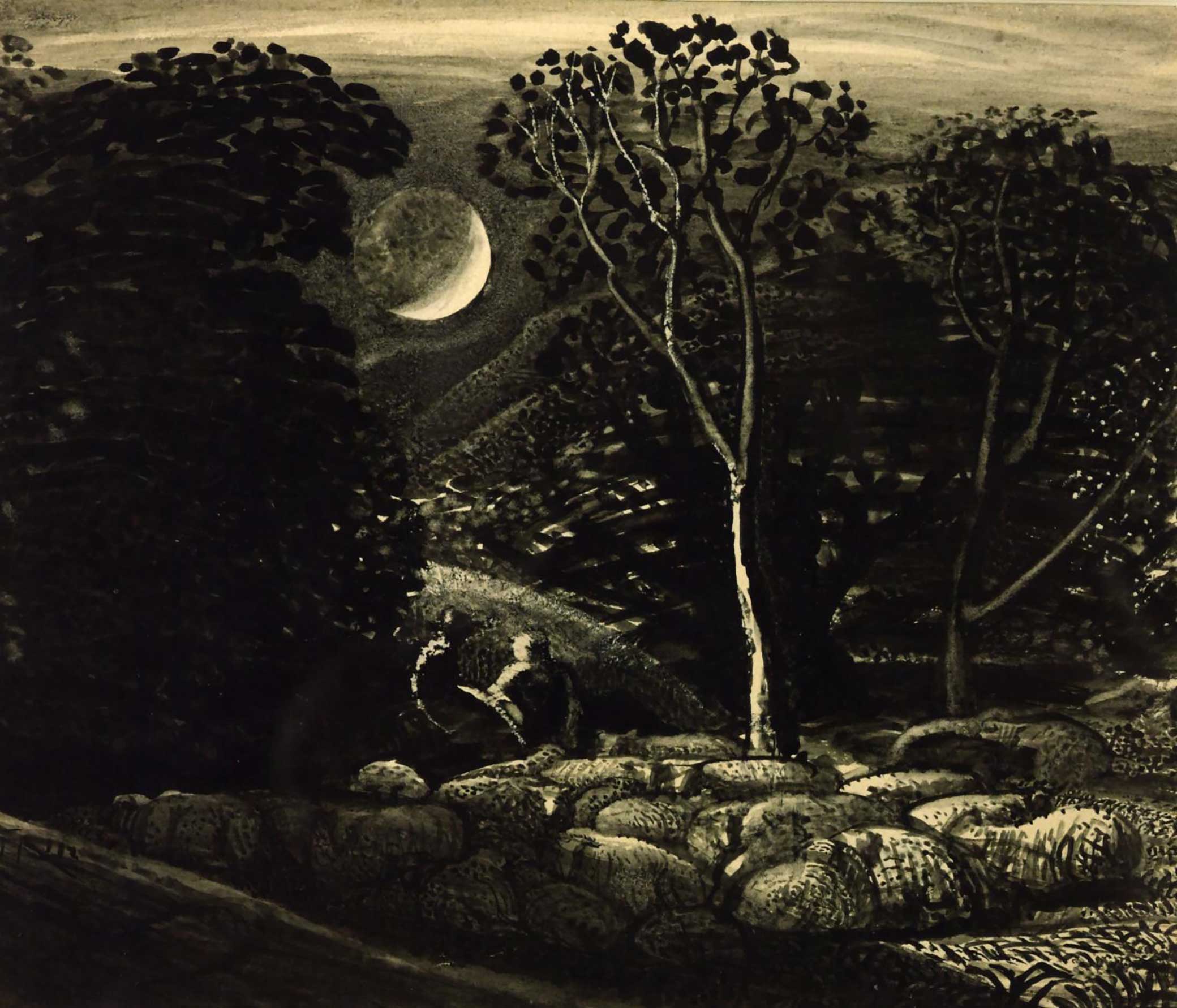

Moonlight, a Landscape with Sheep, by Samuel Palmer, c. 1831. Photograph © Tate (CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0)

The Great Death was the most deadly recorded calamity ever to have struck humanity—and may well still be. Between 1347 and 1351 it is estimated to have killed 75 million to 200 million people across the world. It was certainly the worst naturally occurring (i.e., not anthropogenically exacerbated) disaster part of the world had ever recorded. It saw 40 percent—even half—of England’s population, and much of Scotland’s and Wales’, bowled down like skittles in the spring, summer, and autumn of 1348 and 1349. This disaster came on the back of the widespread famines and terrible floods brought about by, or at least coinciding with, the deteriorating climate in the 1310s as the Medieval Warm Period gave way to the Little Ice Age. Many thought they were soaking up the last glimmers of the universe’s existence. “So many died,” wrote the Italian chronicler Agnolo di Tura, “that all believed it was the end of the world, and no medicine or any other defense availed.”

It is impossible to say exactly how the inhabitants of Wharram Percy in North Yorkshire, often described as “Europe’s best-known deserted medieval village,” experienced the plague. Established in the late Anglo-Saxon period, between 850 and 950, Wharram Percy exists on the site of an earlier Middle Saxon settlement, and was continuously occupied for around six hundred years. It was part of a broader trend—the rise of the village. No one could have known that the village lay in the “shadow of annihilation.”

Death came suddenly. You might go to bed well, wake up ill, and, in the afternoon, die. Or, as one chronicler put it more optimistically, “those in the prime and vigor of youth…breakfasted in the morning with their living friends, and supped at night with their departed friends in the other world.” Priests dropped down dead at the bedsides of the sick and gravediggers fell into the very pits they had just dug. Rural communities like Wharram Percy were shattered, workforces decimated, entire families obliterated in the blink of an eye. Very rarely did anyone who contracted the Pestilence last longer than five days. Boccaccio recalls how most died within three. At Wharram Percy, and villages all over Britain, vacant cottages and deserted farms abounded, the doors of longhouses left ominously ajar.

Some places struck by the Pestilence never recovered. Tilgarsley, near Eynsham in Oxfordshire, was once a large, thriving village. Before the plague struck, it had more than two hundred residents, including twenty-eight taxpayers, but in 1359 the Exchequer learned that the entire population had vanished, laid low, it is recorded, by the Great Death. This is obviously a slight exaggeration—some tenants would have moved away of their own accord, lured by more attractive tenancies, and several members of prominent local families survived—but the village lay in ruins and the landowning abbot was granted relief from paying any future taxes. That Eynsham, its similarly sized neighbor, survives is testament to the peculiar ferocity with which the plague struck Tilgarsley, and we can by now imagine something of the horrors that unfolded there. Nonetheless, the Exchequer was ever hopeful that the community, or a community, would one day return; but it never did. By 1422 it was a lost cause, carved up into agricultural leaseholds.

Sometimes the memory of lost villages can be eclipsed by other historical resonances. We know there was a village called Ambion in Leicester because it surfaces in the historical record at the end of the thirteenth century, but after 1346 it is never heard of again; no doubt it was ravaged and depopulated by the plague. Yet Ambion Hill overlooks Bosworth Field, where Richard III, last of the English kings to die in battle, lost his throne to Henry Tudor in 1485. He pitched his camp on the hill overlooking the deserted village the night before he met his doom, and the haunting ruins of longhouses, ponds, manor house, and the overgrown street may well have still been visible below. History is silent on whether or not his troops gazed down upon the mournful sight as they reconciled themselves to the prospect of death in battle.

It must be said, however, that the Black Death was nothing like the great exterminator of villages (and even towns and cities) it is frequently made out to be—in popular culture, online, and indeed in the writings of contemporary chroniclers. Contemporary chroniclers were not necessarily being histrionic (though they did like drama)—they had every reason to believe that “many such little villages would never again be inhabited,” as Henry Knighton put it. When you are in the middle of a pandemic, or in its bleak aftermath, it can be hard to see the light ahead. And indeed, as the social and economic life of the country ground to a halt, Britain became one great shadowland—but not one that endured. But in reality the vast majority of villages (and all the towns and cities) did survive in the long term—albeit, in some cases, in shrunken and more fragile form. So long as houses could be renovated, crops cultivated, and the church restored, it made no sense to found a new settlement when an existing one could be reoccupied.

And yet, in the two hundred years following the Pestilence, thousands of rural settlements did vanish from the map. That is not to say the Great Death did not have a profound impact on England’s topography—it did. It can be linked to the disappearance of thousands of villages, but in a complex and indirect way, one that was certainly not foreseen by the chroniclers. For when the scythe came down upon England’s villages en masse in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, it came from an unexpected quarter.

The lord of Wharram Percy died very shortly after the plague had reached Yorkshire, in 1349. It took its terrible course, killing a third of the population and leaving forty-five shaken souls. The death of the lord of the manor resulted in a brief period of direct royal control since the heir was a minor. When he died, around twenty years later, the estate fell into the hands of a more distant branch of the Percy family and thereafter the Percys were absentee landowners. By the late fourteenth century thirty houses were occupied, the uncultivated land was sprouting crops once more, and one of the mills had been restored to its former glory even if, by the fifteenth century, the village had shrunk to half its original size. In 1400 the Percys swapped Wharram for a manor owned by Baron William Hilton, who became the new landlord, thoughtfully replacing the upper story of the bell tower but, it seems, not actually living in the village either. When this new overlord died in 1436, and the village passed on to his heir, Wharram was a distinctly less bustling place—sixteen of the houses were occupied. But by now, as the economic advantages of sheep grazing over cereal farming became more manifest, and across England highly tilled arable land was converted to enclosed pasture, the village was living on borrowed time.

The evictions began in 1458. Gradually, the residents were served their notice, their houses ripped down or left to fester, and sheep moved in. Some, finding more advantageous tenancies elsewhere, left of their own accord; others were flushed out by Baron Hilton. By the dawn of the sixteenth century what few houses were left were occupied by smallholders and a few lonely shepherds. The last arable strips were finally converted to pasture on the eve of Henry VIII’s quarrel with the pope, in 1527, and only a “chief messuage”—probably a well-preserved medieval longhouse—remained. What happened at Wharram Percy was a perfect microcosm for what was happening nationwide.

The fifteenth-century chantry priest and historian John Rous leaves us an impassioned and detailed account of the sheep enclosures of the mid- and late fifteenth century which destroyed so many villages in a twelve-page digression in his Historia Regum Angliae (finished 1486), written thirty years after the first evictions at Wharram Percy, and composed during the time that Henry VII, the first of the Tudors, came to the throne. Rous says he was “stirred to rise against [the devastation and destruction of villages] by mouth and pen following the clamor and murmurings of the populace,” having presented petitions to Parliament in 1459. The occasion for his invective, within his grand narrative of English kings, is his account of William the Conqueror’s Harrying of the North, when the Norman invader laid waste to dozens, possibly hundreds, of villages to bring his northern subjects to heel. That, Rous says, was bad enough. But it is not a patch on “the modern destruction of towns” which flowed from “the worship of Mammon”—avaricious landowners putting private gain above the common good by converting arable to pasture without the consent of their hapless tenants. In his history, John Rous gives us a list of villages and hamlets that have been destroyed or “grievously ravaged” by avarice, as Wharram Percy would be. He lists seventy-eight, all within his home county of Warwickshire. Of all of Rous’ vanished—or vanishing—villages, the vast majority are still deserted today, festering beneath a sea of grass for almost 550 years.

In total, several thousand medieval villages vanished. Thanks to the labors of the Deserted Medieval Village Research Group, and drawing upon sources such as Rous, we have a map that plots England’s shadow medieval topography, victims of the economic consequences of the Black Death. As the map reveals, the ghost villages were by no means uniformly distributed throughout England but instead were particularly concentrated in certain counties. Each one of these was potentially a tragedy for at least some of the evicted tenants, and so the landlords attracted much opprobrium and the whole process was seen as a pernicious social ill. John Rous castigates enclosing landlords as “murderers of the impoverished,” “destroyers of humanity,” and “venomous snakes.” They had showed no mercy to “the children, tenants, and others whom they have forced from their homes by theft,” and so could expect “judgment without mercy” in the afterlife; certainly he would not be singing any masses for the souls of these “destroyers of towns.”

Worried by the social and economic effects of the enclosures, in 1517 Cardinal Wolsey set up a royal inquiry. The Domesday of Enclosures is highly evocative as a symphony of mini-tragedies in which we can sometimes hear—mediated through the depositions—the anguish of the dispossessed. The eighty people evicted from Stretton Baskerville in Warwickshire were “compelled to go from thence unwilling and unlamented turning sorrowfully to idleness, to drag out a miserable life, and—truthfully—so to die in misery.” “Truly they have died,” it reaffirms, “in such a pitiful state.” Human stories like these lie behind all the evictions. The new landowner “willfully allowed the houses to fall to ruin and turned the fields from cultivation to be a feeding place for brute animals.” Here, as in so many other deserted villages, including Wharram Percy, the abandoned parish church became a terrible symbol of depopulation, a pitiful place where “animals take shelter from storms and feed among the graves of Christian men in the churchyard, so that it and the church are desecrated and profaned.”

Not long after the villagers of Wharram Percy were driven out, the landscape degenerated. Where once there had been cornfields, blades of grass now straggled; where once peasants had tilled in open fields, sheep—1,240 of them by 1543—munched and bleated between thick hedges. The mud-and-wattle cottages were demolished and burned for firewood or were torn down by the wind. Rain washed through untrodden soil and tumbleweed billowed through lonely lanes and roads. In storms, sheep and cows fled to the church, cowering beneath the nave, and when the rain ceased they grazed above the dead to repeated clerical consternation. Eventually, salvagers turned up, reducing some of the church to a sad heap of rubble. At one point a man lay down beside one of the ruined houses’ walls and died, rotting away until slates and tiles cracked over his rib bones. It is tempting to think of this person as the village’s final resident, obstinate to the end, but more likely he was a famished vagabond. His bones were excavated in 1964.

Excerpted from Shadowlands: A Journey Through Britain’s Lost Cities and Vanished Villages. Copyright © 2022 by Matthew Green. Used with permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.