Man in a Top Hat, attributed to John Scarlett Davis, c. 1838. Photograph © Tate (CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0).

A telling aspect of the magic hat, as a physical thing, is that its form is often mundane, appearing in the shape of a traveler’s or laborer’s hat, such as a cap or a simple fedora. Described as a “coarse felt hat” in an English play about a wishing hat published at the turn of the seventeenth century, and in a nineteenth-century Grimm’s fairy tale as a “little old worn-out hat” that “has strange properties,” it is similarly defined in many stories.

The magic hat’s association with the commonplace has continued into modern times. For example, the top hat used in the magician’s show, though linked with the wealthy, was a style worn by many men and women who lived on the lowest rungs of the class system. The Harry Potter Sorting Hat, so probing that “there’s nothing hidden in your head / The Sorting Hat can’t see,” was an old, bent “pointed wizard’s hat” that was “patched…frayed and extremely dirty.” The sacred hat, too, in many cultures has been based, like the magic hat, on the commonplace.

A cap, as a hat form, is one of the oldest types of headwear. The etymological root of the word cap, as historian Beverly Chico plausibly suggests in her encyclopedia of hats, comes from the Germanic haet, meaning “hut,” and is connected to the Belgic Briton word cappan, meaning “wattle huts or cabins.” In these meanings, she sees the cap as a covering akin to architecture.

The Century Dictionary connects cap to words for cover, such as hood, cowl, and the like, but finds the connection to hut uncertain. However, it is not far-fetched that the word cap is about covering (as in its use as the verb “to cap”). It is a derivative of cappen, from which cowl and cloak evolved, and is also connected to the Latin capere, meaning “to take, take in,” because it “envelopes the whole person.” Concealment and deception is also associated with cap, evident in its use in nineteenth-century English slang, where it conveyed deceit. To “set one’s cap” meant to “deceive, beguile, or cheat.” This connotation, if not denotation, of cap also occurs in the slang usages of bonnet. In the form of nineteenth-century British street slang known as cant, a bonnet meant a “gambling cheat or decoy,” as well as being simply a stand-in for “cheating” itself. It was also associated with treasure or money through being used to mean “bankrupt,” because a bankrupt person was made to wear a green bonnet.

The cap that can conceal, beguile, or cheat is a recurring feature of the magic hat. One of the earliest known versions is that of the magic felt pileus worn by the ancient Greek god Hermes, which, shaped like a small cone with no brim, was common headgear among working men. Hermes’ hat hid him in invisibility and could transport him through flight. A trickster god of theft as well as the deity who took the dead to the underworld, Hermes also represented the arts in invention and literature. He was additionally the patron of travel and so closely associated with it that he later wore a traveler’s hat, known as a petasos. His pileus appears in the Homeric epic the Iliad, where it was lent to the divine Athene to conceal her in battle.

In the Iliad, the cap was known as the Cap of Darkness or the Helm of Death, in part because, at that time, it belonged to Hades, the god of the dead, but had been given to him by Hermes. That Hermes was in a position to bestow his pileus on a deity as important as the god of death emphasizes that, of the two gods, Hermes was the older deity. Hermes had an archaic role that has been identified as that of a time figure because he was conceived as a fertility spirit in the millennium before the ninth- or eighth-century bc era of Homer. In this early form, Hermes drew together the concepts of both life and time into a cycle of birth, decay, death, and renewal that occurred within what the ancient Greeks saw as a period. This concept of period was a specific sense of time passing and was measured by the idea of waxing and waning, a kind of measurement more fluid than a time-construction such as “year.” As such, Hermes is a figure associated with life and temporality. It is important to see that Hermes’ magic pileus carries these connotations in antiquity because, though many ancient myths are lost, clues to meaning can be traced through later mythic figures and the physical symbols they carry.

The emblematical pileus was worn also as a life symbol by two other early Greek divinities, the male twins Castor and Pollux, known as the Dioscuri, who were born from a single egg and whom Carl Jung construed as time figures, as in ancient myths they were representative of mortality and immortality. Jung further interpreted the twins’ purpose—portrayed, as they were, emerging from the life egg—as representing the act of becoming aware when consciousness is raised out of the dark unconscious. This association of the magic hat with time, awareness, and consciousness is something that also appears throughout many later tales of the magic hat.

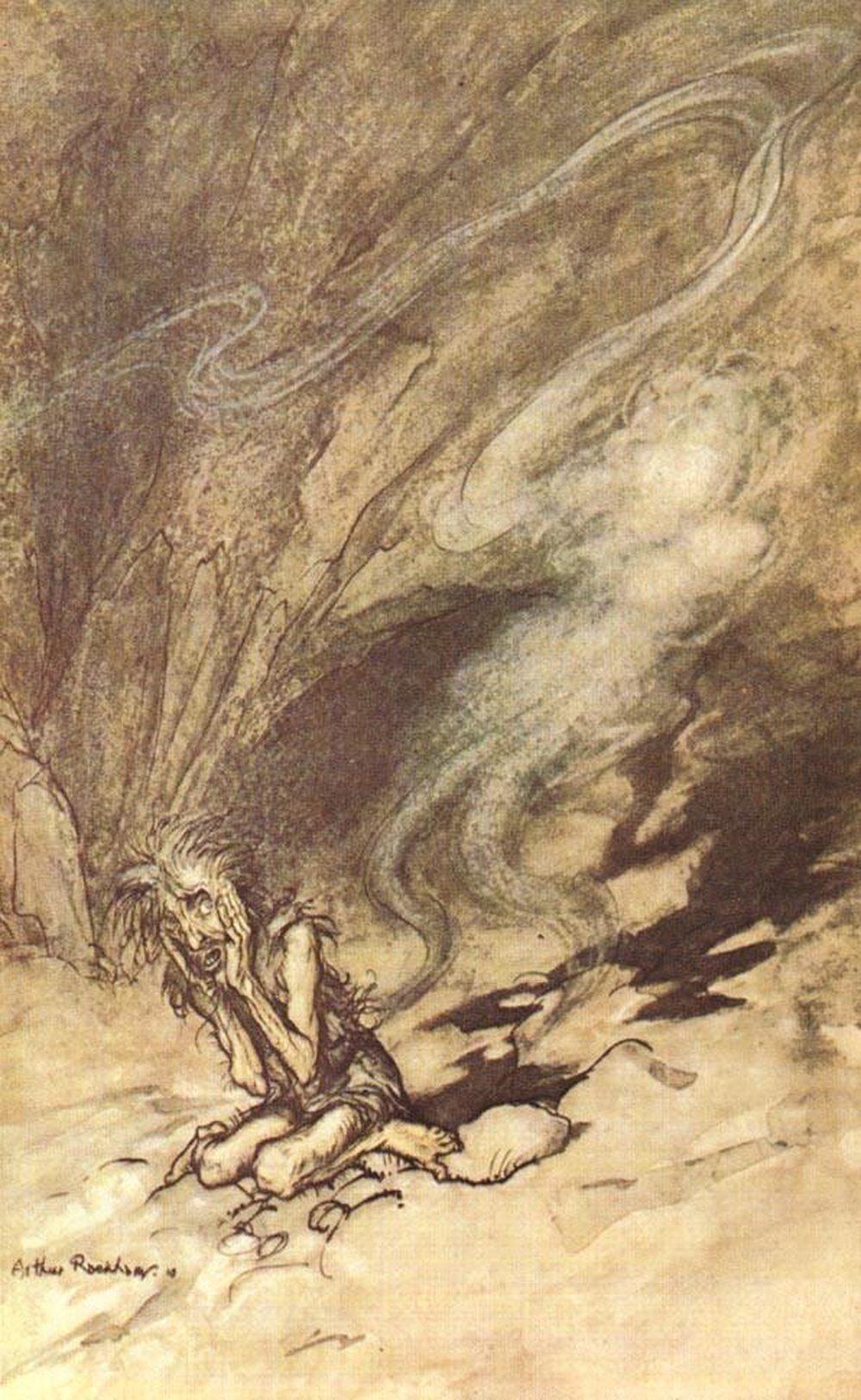

The mystic elements that mirror the process of conscious thinking appear in later European stories of a magical hat. In the long, complicated eleventh-century Old Norse Nibelungenlied epic, which is based on much older oral tales, there is a magic cap, tarnhelm (or cape, the tarnkappe), which leads the heroic male, ultimately, to understand secrets of the natural world and comprehend the language of animals. The wishing hat as a version of something magical that opens the door to greater awareness appears again in the sixteenth-century German tale of Fortunatus. Though this story’s history is in the oral tradition, its first publication as an anonymous tale has been traced to 1509 in Germany. It became the basis for Thomas Dekker’s English play The Whole History of Fortunatus (1599) and his later version, The Pleasant Comedie of Old Fortunatus (1600). Immensely popular, the story and play were much published, much translated (thirteen languages), and much performed well into the eighteenth century.

The Fortunatus story certainly reflected the burgeoning mercantile world of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, because it told a morality tale of a poor man who becomes a wealthy merchant, in part through the gift of a magic (ever-filling) purse. He marries, has two sons, and builds up a rich trade over the course of his travels, during which he steals the “Wishing-hat” (from a sultan, signifying that his business extends to the East) and the hat enables him to instantaneously, swiftly fly away. His interest is in money, but it is his younger son who, on the verge of his execution, recognizes the Wishing-hat’s value. He marvels that the hat offers the truer wealth of knowledge, exclaiming, “I have…knowledge in my Hat” and realizing that the hat could have brought him “Experience, Learning, Wisdome, Truth.”

In Dekker’s play the wishing hat is used to transport the wearer. There is a context, however, in which the hat causes those who wear it to experience a broader range of qualities. The “Wishing-hat” of the play is involved in deceit and transport (Fortunatus steals the hat and zooms off). But the play ultimately reveals the wishing hat to be about offering knowledge and wisdom, which are both, in the tale, tied to the experience of speed, theft and travel.

These same qualities are found in Hermes’ magic pileus and, it was been argued, are reflective not of literal travel or treasure but of the process of traveling in thought and the riches of knowledge. They reveal the essence of Hermes as a deity focused on the act of knowing. His divine capacity was to generate and protect invention, literature, thieving, travel, cunning, and deception. He also represented the life force and the process of time (as waxing and waning), and in this he was the stable longevity that produced these arts.

These riches of knowledge appear in the wishing hat of The Blue Bird (1908), by Belgian playwright Maurice Maeterlinck. His play’s magical hat offers two children a discovery of the unknown when it opens their consciousnesses by showing them the souls of objects and animals. In the 1918 film version directed by Maurice Tourneur, costume designer Ben Carré created the hat as a beanie with a long pheasant feather. This was a riff on nineteenth-century German walking hats, touching on the wishing hat’s archaic fundamentalism (a beanie is a skullcap), its ancient themes of the commoner and travel (it is a peasant hat and a traveling hat), and its modern life (the children’s contemporary search)—all emphasizing how the wishing hat blurs the worlds of the everyday and the preternatural.

These elements of the magic hat as a thing of creativity was fascinatingly posited by the famous collector of fairy tales Jacob Grimm, in his nineteenth-century work on German folklore, Deutsche Mythologie. He connected the word wish etymologically with the name of the supreme Nordic deity, Wodan, a god who had a wishing hat that made him invisible, and argued that the words were connected because the divine force in Wodan and the actual forceful act of making a wish were the same thing. Grimm extrapolated on this idea by underscoring that the verb to wish is about an action. The action of wishing is designed to result in making something manifest or causing something to happen. It is an action verb. Grimm underlines that a wish is less about longing than it is about the creation that the wish wills into being. As he puts it, the wish produces the action of a “melting, molding, casting, giving, creating, figuring, imaging, thinking faculty, hence imagination, idea, image, figure.” Grimm links the wish, therefore, with creation and sees it as a creator just as a god is a creator. He connects it both to personal activation—“there is about Wish something inward, uttered from within”—and to divinity—“God imparts wishing.”

The magic hat manifests speed in the same way that the mind does because the hat’s talents parallel the speed of thought. The hat opens up new worlds quickly and goes into unheard-of (and undiscovered) areas, just as the mind opens up the spatial vastness of the imagination. The hat continues into modern times as a magic vessel, imparting knowledge and meaning as if it were a kind of theatrical stage and opening the doors of the mind as if an alphabet waiting to be read.

Like the magic hat, the mind conceals and reveals. It moves with lightning speed and can arrive at another thought or another subject (realm) instantly. It has cunning. It appropriates ideas. It is an unending trove of wisdom. The magic hat enables the wearer to penetrate unseen boundaries, enter into the inner world and supernatural world. It brings freedom from the laws of time and space. It enables the wearer, as a person open to multiple possibilities, to enter the world and see its true structures of the finite and the infinite, and also to enter the self, and find the true self. These are the same qualities that the everyday hat carries. It places the wearer both in a social category—of traditional mores or fashionable modes—and in a private world of self-perception, identifying herself or himself as unique but as part of the larger world.

Reprinted with permission from Hat: Origins, Language, Style by Drake Stutesman, published by Reaktion Books Ltd. Copyright © 2019 by Drake Stutesman. All rights reserved.