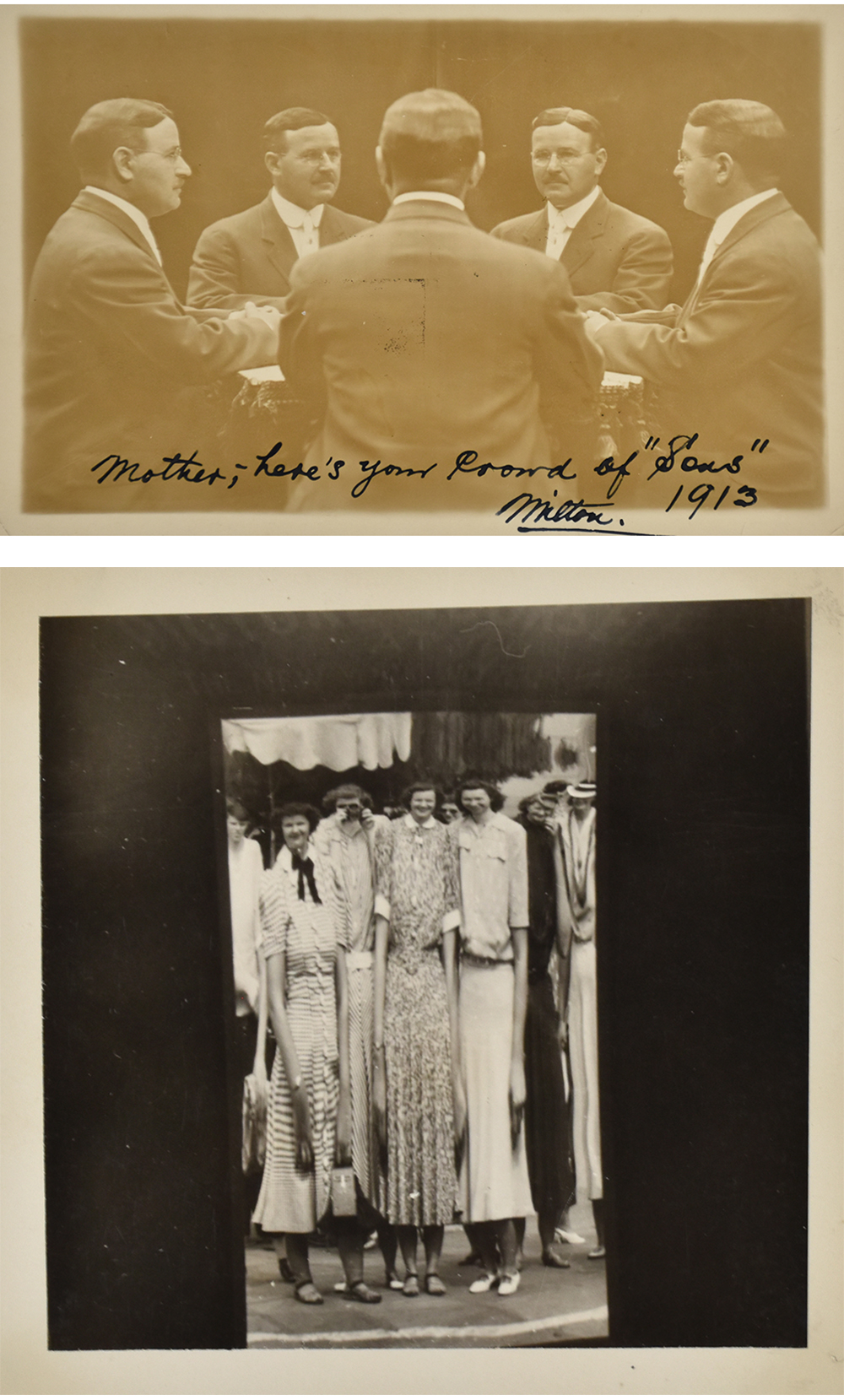

Pages from Walter E. Woodbury’s Photographic Amusements (1897). Internet Archive.

Tortured by their relentless work ethic, the editors of the Oxford English Dictionary define an amusement as an idle, time-wasting diversion or entertainment. When the term was applied to the practice of trick photography in the late nineteenth century, the trend’s supporters were quick to point out that “photographic amusements” were not just entertaining but also educational. Making a photograph of a ghost or creating a self-portrait inside a glass bottle taught novices about accidental double exposures. Photographers learned the medium by pushing it to its limits.

Despite its educative potential, the genre was largely disavowed by the photographic establishment, as well as later histories of the medium. In their bid for respectability, nineteenth-century photographic commentators leaned heavily on the medium’s association with truth and objectivity. They staked photography’s fortune on faithful likenesses and accurate documentation. That trick pictures, such as the hall-of-mirrors pictures called “multi-photographs,” ended up as carnival attractions in the twentieth century seems to justify these suspicions.

Today photographic amusements still remain beyond the boundaries of fine art, but they are hardly at the periphery of photographic practice. Adobe’s annual revenue is more than ten billion dollars and Snapchat, home of augmented reality masks galore, IPO’d at three times that amount. In 2013 a popular blog called Filter Fakers allowed users to submit links to Instagram photos that claimed #nofilter. Filter Fakers analyzed the photos digitally in order to debunk claims of authenticity, then republished the offending photos along with the name of the filter used and the Instagram user’s handle. More recently, the fad for unmasking celebrity Photoshop fails has revealed a similarly zealous pursuit of photographic truth. Facetune, a photo-editing app, allows users to erase edges and bend lines, slimming and creating curves in portraits to mimic professional photographic retouching. Inexpertly edited photos often include wavy walls behind newly narrowed waistlines. In the nineteenth century as well as today, photographic trickery trains viewers to be more careful consumers of visual media by teaching them how to break the rules themselves.

Trick photography emerged as a popular practice in the 1890s following the advent of small, handheld cameras, such as the Kodak. Previously, photography had been the domain of scientists or professionals who could afford the expensive equipment and dedicate time to the mastery of darkroom work. As the cost of cameras decreased and the photo-finishing industry was born, the medium became more accessible to amateurs. A Kodak user could simply send the camera with its finished roll of film back to the manufacturer. The pictures were developed and printed, then returned to the photographer along with the camera, now reloaded with a fresh roll of film. As the company’s advertising slogan put it: “You push the button, we do the rest.”

But amateur photographers still had quite a lot to figure out besides how to press a button. Early amateur cameras were not equipped with light meters, focusing rings, or even viewfinders. Making pictures involved trial and error, as well as an understanding of the basics of exposure, focus, and framing. Sometimes errors were useful teachers: strange results became the foundation of popular trick photos. Underexposing glittering sunlight could transform any scene into a nocturne, which became known as day-for-night shooting. Exposing a single negative twice to produce twins became a mainstay of trick photography though it remained a mistake elsewhere, the result of forgetting to advance the film.

Aspiring trick photographers who wanted more guidance could consult a book. Trick photography was sometimes featured in a slim chapter of its own at the end of amateur how-to guides. But several titles were entirely dedicated to the practice: the German Photographischer Zeitvertreib (1890) and its British translation Photographic Pastimes (1891), as well as the French Les récréations photographiques (1891) and the American Photographic Amusements (1896). Walter E. Woodbury, author of Photographic Amusements, claimed that his book was not aimed at simple button pushers, but many of the tricks he described could be accomplished with a Kodak. The first examples in the book are amusing even without a camera. Using mirrors, the photographer could create a battery of soldiers from just one sitter or the illusion of a cardsharp playing against himself. Woodbury allows that “even an ordinary, well-polished spoon may be made to give some curious results.”

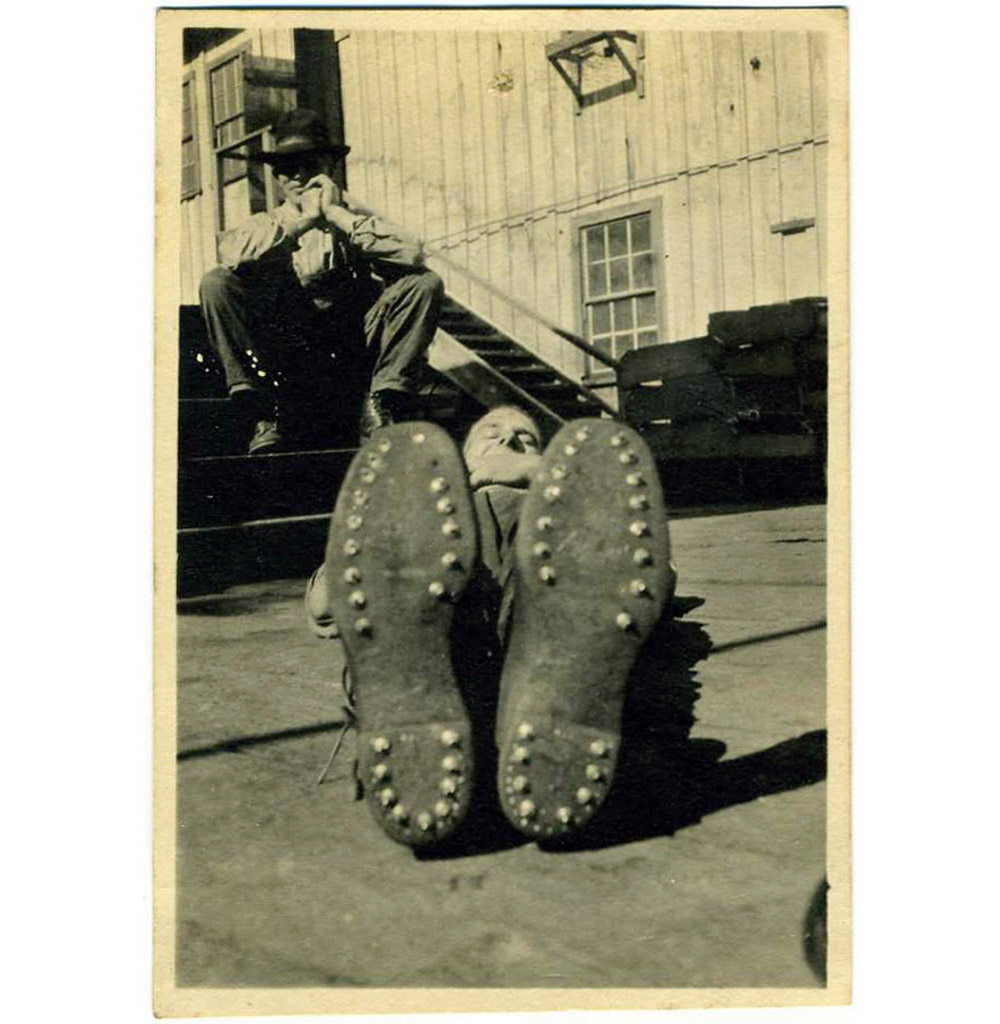

In the traditional instructional literature, however, such curious productions still belonged to the scrapheap, rather than the scrapbook. Distorting lens effects were among the most significant challenges faced by early portrait photographers. In seated poses, feet and hands presented special problems for the photographer. Placing the hands on the knees while facing forward would exaggerate their size through the effects of foreshortening. Crossing a leg and allowing the foot to break out of the body’s focal plane resulted in a blurry foot looming in the foreground. Charles Maus Taylor, author of the 1902 amateur manual Why My Photographs Are Bad, described these errors as the consequence of situating the camera too close to the subject. He wrote of the offending extremities, “Those members will naturally be reflected as larger in proportion to the rest of the body; and in the finished picture will displease the eye by their exaggerated size.”

Photographic Amusements capitalized on these distortions in a popular trick picture punningly called the “photographic feat.” In this genre, the soles of the sitter’s shoes dominate the picture, while his face peeks out from the seemingly distant background. Woodbury explained, “The effect of using a wide-angle lens under ordinary conditions is to make objects in the foreground appear ridiculously large, while those in the background have a diminished appearance…it is hardly necessary to observe that the gentleman’s pedal extremities were not so gigantic as represented in the photograph.”

Another favorite relative scale trick was the “fish picture.” Woodbury introduced the genre: “It is the usual custom of anglers, I believe, to view their captures through magnifying glasses before discoursing upon them. A better plan, however, is to photograph your fish, and then there can be no dispute whatever, because it is the popular belief that photography cannot lie.” The trick requires the hyperbolic angler to hang his microscopic catch from the limb of a tree with black thread, then stand several feet back, posing as if he were holding the fish aloft. Using a small aperture, the lens compresses the distance and keeps both fish and fisherman in sharp focus.

These types of pictures were so popular that even a more conventional how-to book of the same period asserted: “Every amateur is doubtless familiar with the class of pictures which show the subject with distorted feet, but it is not every photo of this class which is a success and it is seldom that we see an example in which the entire picture is in focus.” In these more rigorous, less amusing guides, the fun came with yet more rules. The author cautioned: “To take even a good ‘freak’ picture one must thoroughly understand the underlying principles and must have the proper apparatus.”

Tricks may have taught photographers how to appropriate the medium’s shortcomings to amusing ends, but the practice also revealed anxieties. Long before photography was considered art, these photographers were still fighting for the respectability that they thought would come from professionalization. Trick pictures threatened this goal not only because they undermined the medium’s truthfulness, but also because they recast the rules of photography. If mistakes were celebrated, then the hard-won technical prowess of professionals was called into question.

At the same time, some early professional photographers adopted tricks as a business model before cameras were widely available to amateurs. The production of twins or multiples in still photographs was initially one of the medium’s most sophisticated amusements, allowing experts to profit from darkroom errors. Before plate glass was available inexpensively, photographers reused their glass negatives by dissolving the exposed emulsion and recoating the plate with fresh chemicals. An incompletely washed plate could leave a trace of the preceding portrait, which appeared superimposed on the more recent picture like a ghost. These photographs were popular during and after the Civil War in the United States, when sitters could visit a spiritualist photographer’s studio with the intention of securing one more picture with a recently departed loved one or at least an anonymous ghost. Even Mary Todd Lincoln had herself photographed with the ghost of Abe. By the close of the decade, Lincoln’s otherworldly photographer, William H. Mumler, was accused of fraud. The prosecution argued that Mumler’s photographs, which claimed to represent actual dead spirits for his clients, were fraudulent deceptions.

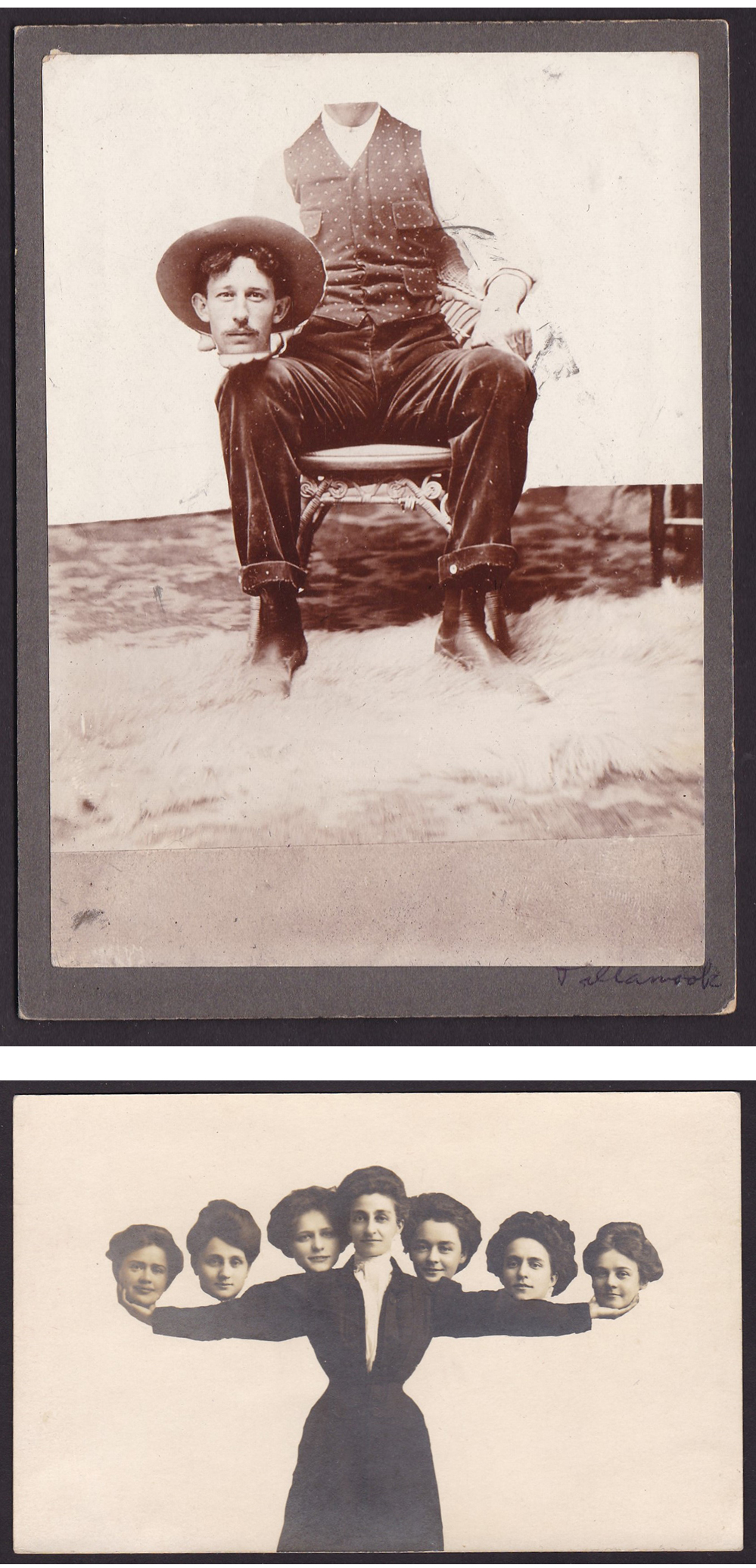

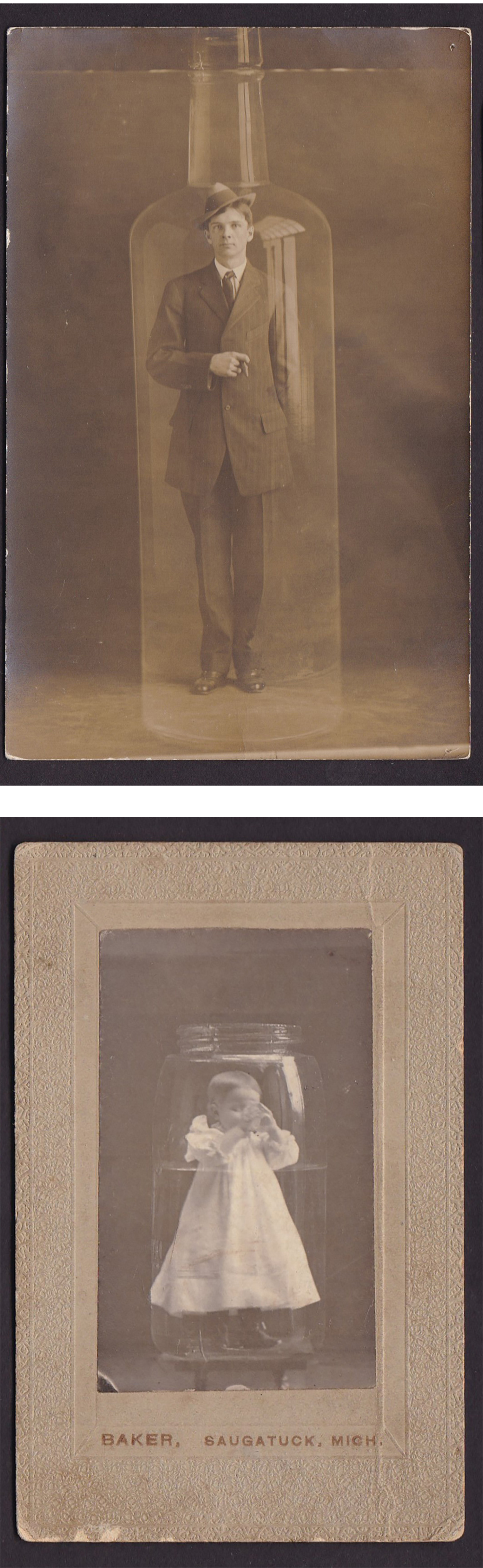

One genre of multiple-exposure photograph taught in turn-of-the-century trick photography guides was far more gruesome than these sentimental Victorian hauntings: the decapitation photograph. “Head upon a plate” or “head in the wheelbarrow” pictures make use of a reduction in scale in addition to double exposure. Multiple exposures could also be used to create person-in-the-bottle photographs.

The photographer first shot the subject in front of a black backdrop, then exposed the plate again, positioning a bottle close enough to the lens to contain the first image.

Long before Photoshop, these tricks were produced entirely in-camera. But just because they didn’t require sophisticated darkroom work doesn’t mean that they were easy effects to achieve. Photographers needed to plan the framing and calculate the necessary exposure times in advance to avoid the trouble of reshooting, especially if they were waiting for their film to be processed by Kodak.

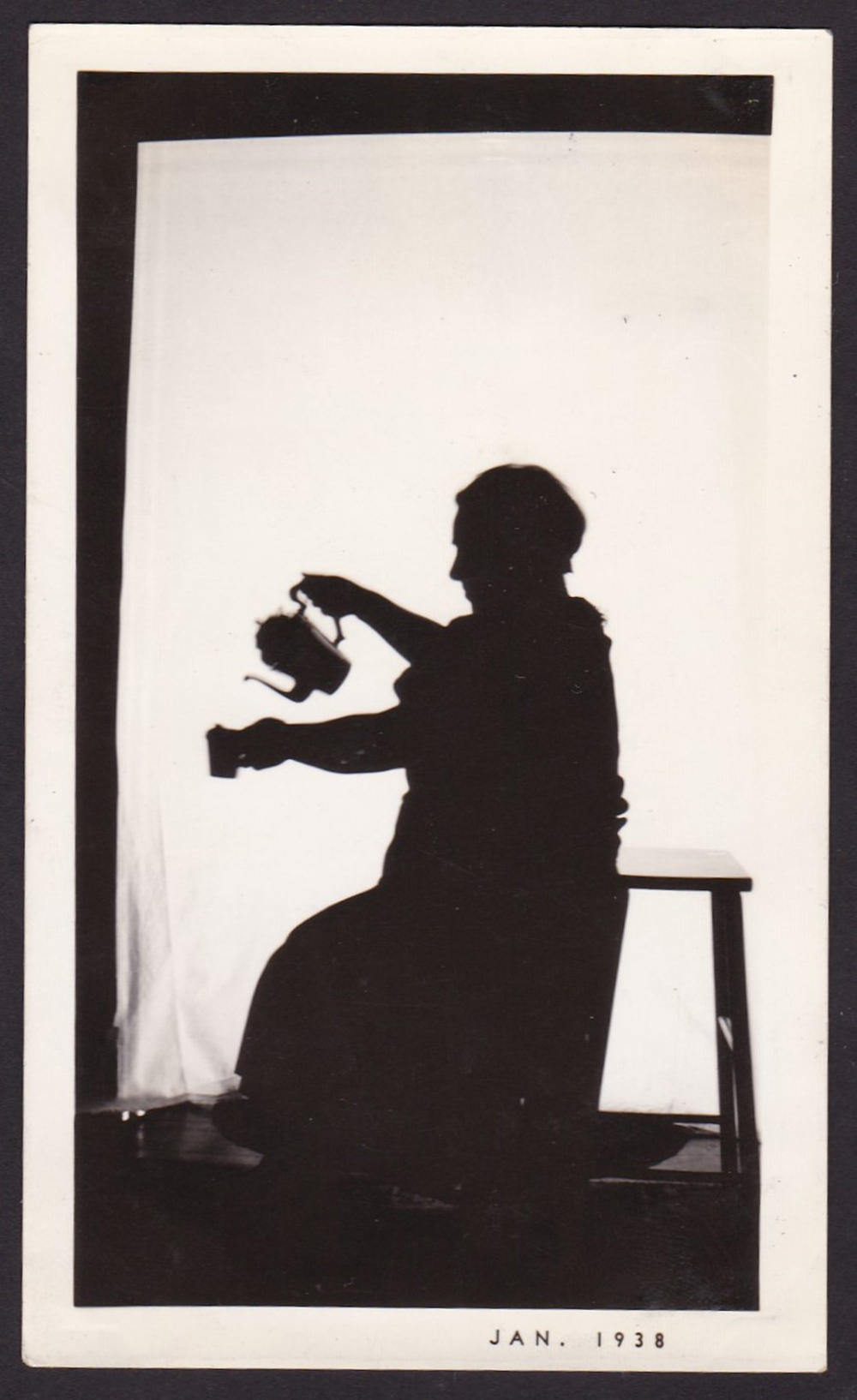

Some photographs that seem entirely ordinary today were once described as trick pictures. Silhouette or shadow pictures were initially classed among photographic amusements. When they eventually made their way into mainstream manuals, the fun was tempered with admonishments about how to make such photographs correctly. The shadow picture is arguably the essence of photography and the origin of all artistic representation, if Plato’s allegory of the cave can be considered history. A more recent history of the shadow picture could be found in the mid-eighteenth and early nineteenth-century vogue for profile portraits, drawn by hand and cut out of black paper. These were later mechanized by the physiognotrace machine, which allowed the sitter to trace her own profile. In the twentieth century, Kodak’s manual How to Make Good Pictures took care to describe these earlier examples of profiles as art: “Many of the excellent silhouettes that were made at that time, especially those of our presidents and other public men, are now preserved in museums.”

Making a perfect photographic silhouette was even more involved than these precedents, because of film’s sensitivity to light. Any inconsistency in relative tonality would result in an imperfect silhouette with areas of shadow showing through the light background or vice versa. Photographic Amusements recommends constructing a “tunnel” of dark fabric on either side of a window. Subjects pose in front of the window but behind a white sheet, rendering them backlit shadows for the camera’s lens.

Elsewhere, such high contrast between light and dark areas of the image would be described as one of photography’s greatest failings. Robert Hunt’s 1853 Manual of Photography admonished photographers: “The great defect in nearly all the photographic pictures which are obtained is the extreme contrast between the highlights and the shadows, and in many an entire absence of the middle tones of the picture.” As in the case of lens distortions, this photographic trick required that photographers creatively break the rules of the medium. In so doing, silhouette pictures also taught photographers to scan a scene carefully, previsualizing it in terms of relative tonality. Creating a perfect silhouette is easier now, but it still requires that the photographer know how to override some of the smartphone camera’s most advanced features, such as automatic flash or night mode.

The unabashed fun of photographic amusements is visible today in TikTok videos, which are equally a lesson in performing and video editing, as well as a pastime for viewers (also known as a time suck). Hours of practicing dance moves, location scouting, and editing are all distilled to a few seconds of pure bliss or dissipation, depending on your perspective. Rarely, if ever, has TikTok been described as educational, but, like photographic amusements, the app is also a teacher—albeit a cool young one. The “delayed” filter, which leaves a trail of clones behind performers as they move across the screen, is a filmic version of trick photography’s popular duplication and ghosting effects. Magic costume changes, such as #clothesswap and #outfitchangechallenge, confound the continuity of time and space that is standard in industry productions by creating a match-on-action cut within the original scene. Without Hollywood stage sets and film editing bays, TikTok users amuse viewers by sending up the conventions of more polished productions. More than a hundred years earlier, photographic amusements took all the seriousness of professional photography and undermined it with messy, outlandish, impossible hijinks.