The Sigh, by G. Kellaway, 1828, after T. Stewardson, 1828. Wellcome Collection.

For a long time, men’s lives dominated discussions of middle age. The idea of “climacteric” or “critical” years is found in the Roman grammarians Censorinus and Aulus Gellius and other ancient writers, who attributed it to even older Egyptian or Chaldean roots. According to this concept, human life proceeded by steps of seven (or sometimes nine) years; every seventh (or ninth) year was an annus climactericus. These climacterics brought sudden shifts in constitution.

In children and youths, the climacteric years were seen as steps toward maturity: in the seventh year, children grew permanent teeth; in the fourteenth, they entered puberty. But every change also implied danger, and among the elderly the profound change their bodies underwent in climacteric years could pose lethal risks. Numerous works explained that people often died in a climacteric year. The deadliest of all was the sixty-third, the annus climactericus maximus or androklas (man-killing), with the forty-ninth the slightly less dangerous “small climacteric year.”

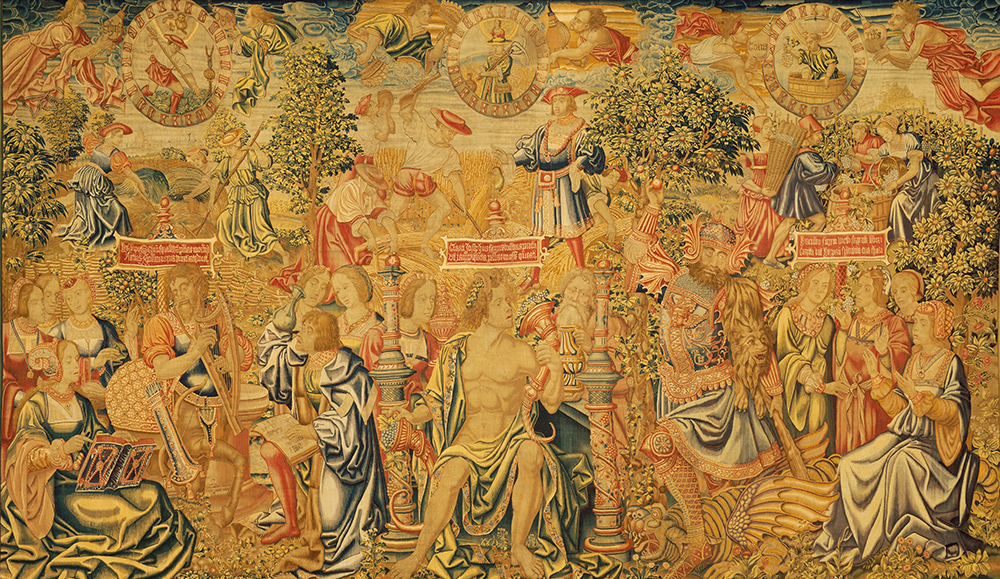

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, climacteric years were described by many authors and discussed at length. Humanists like Giovanni Battista Codronchi and Henricus Ranzovius sought to corroborate the theory of climacterics by compiling long lists of well- and little-known figures who had died in a septennial year. Eulogies, birthday speeches, and funeral orations often mentioned the “climacteric year” that the addressee—most often a sovereign—was about to enter, had just survived, or had succumbed to. Although climacterics occurred in the lives of men and women, the concept was applied to men more frequently. The speeches, like Baptista Codronchi’s and Ranzovius’s lists of the dead, contained men almost exclusively. (The women listed were elite or saints.) This was because men were the measure of humanity but also because they were more prominent: the “critical” years were biographical benchmarks as much as medical measuring points.

Men remained central in modern medical diagnoses of the climacteric well into the nineteenth century, when the climacteric was narrowed down to middle age. Linked to swollen legs and a flabby stomach, a higher pulse, and increased rates of disease, depression, and death, the “climacteric disease” referred to men primarily. In an influential paper, “On the Climacteric Disease,” the physician Sir Henry Halford, a well-known figure in British medicine—a fellow and, later, president of the Royal College of Physicians and physician in ordinary to George III—told the college in 1813 that “though this climacteric disease is sometimes equally remarkable in women as in men, yet most certainly I have not noticed it so frequently, nor so well characterized in females.” Reprinted on various occasions, translated, and included in standard medical dictionaries, Halford’s paper was a key text on the climacteric, still cited well into the twentieth century.

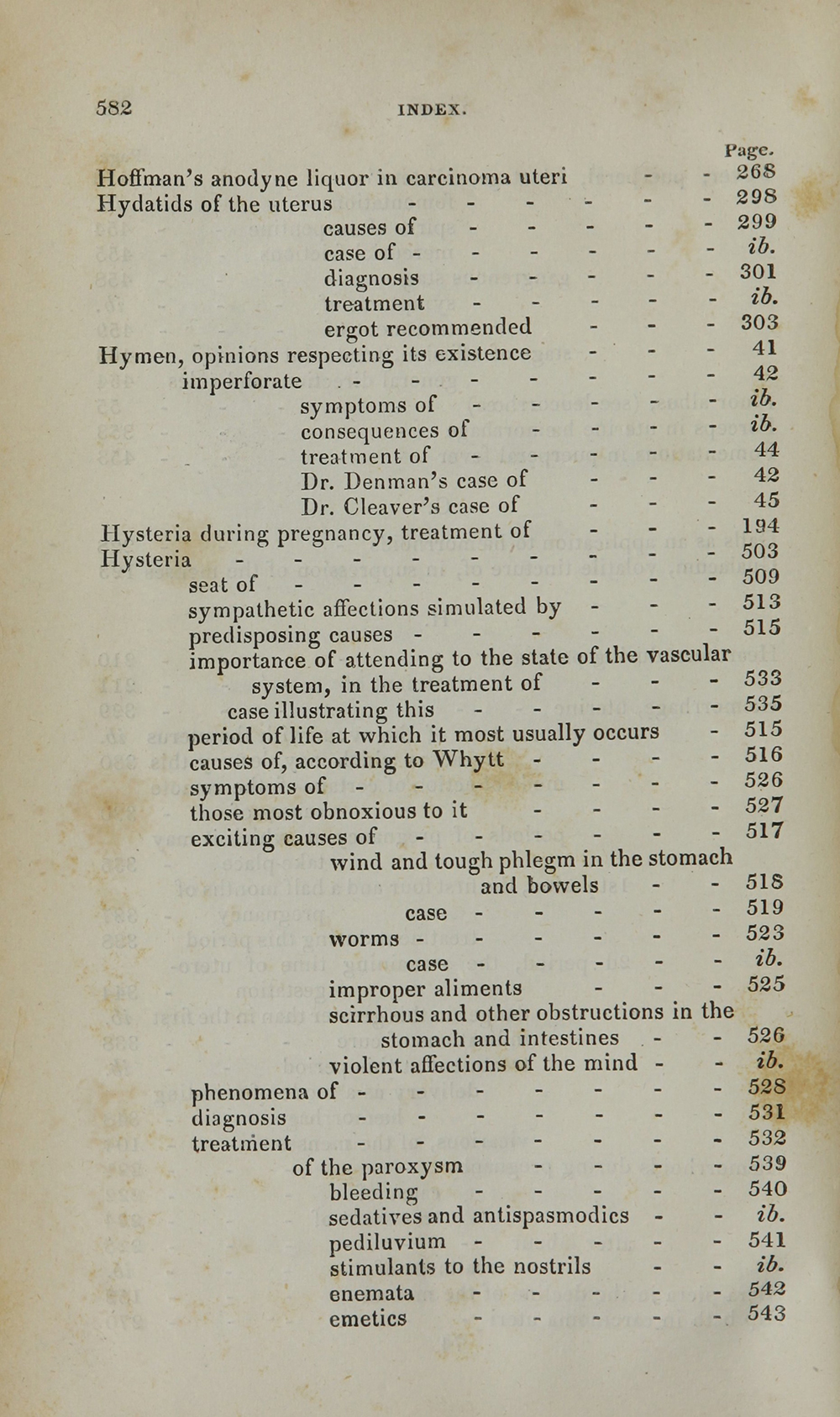

The idea of a “female” climacteric was contested, at least in the Anglophone world. The American physician and obstetrician William Dewees, in A Treatise on the Diseases of Females, first published in 1826 and republished repeatedly in the following three decades, refuted the diagnosis of a female climacteric as a “vulgar error.” Indeed, Dewees asserted, “it would seem that this period of female life is freer from diseases causing death than almost any other.” Most physicians, even gynecologists, were indifferent to this part of the female life cycle. Many gynecological texts had nothing to say about the climacteric in women, and others offered only a paragraph or two, usually to the effect that those who experienced an early onset of menstruation could expect a late cessation. Major textbooks rarely devoted more than a paragraph to menopause. The Index Medicus, one of the leading indices to medical literature, gave menopause its own subject heading only in 1921, and even then referred the reader only to “menstruation, cessation.”

The bulk of medical and moralistic writing was aimed at younger women, addressing declining birthrates in the middle class in particular, and physicians were preoccupied with accounting for menstruation and its disorders. Menstruation was depicted as a debilitating function—prominently invoked, like pregnancy and motherhood, as an argument against women’s growing presence in higher education and the professions. But this did not necessarily mean that the end of menstruation was viewed positively. When they mentioned it, many physicians resisted the interpretation of menopause as a merciful release, which implied, after all, that women might live an active life again. Sometimes they discussed menopause in light of menstrual complaints. When the British pediatrician and obstetrician Charles West, in his 1858 Lectures on the Diseases of Women, spoke about “disordered menstruation,” he called menopause the “permanent” cessation of the menses, mentioning it (if only briefly) next to “premature” cessation, absence of the menses (“amenhorrea”), and menstrual cramps (“dysmenhorrea”).

Like menstrual disorders, menopause indicated nonreproductivity, but so did regular menstruation. When older ideas about menstruation’s purgative, purifying benefits were revised in the later nineteenth century and menstrual flow was connected to the cyclical production of the ovum and thus directly linked to conception, many physicians depicted menstruation as an unfortunate failure in bodily processes designed to build up a fetus. The menopausal discourse mirrored the menstrual one: “What applies to menstruation once a month applies to menopause once in every lifetime.” In the mid-1960s the psychoanalyst Erik Erikson would still depict menstruation and menopause in this light: “Each menstruation…is crying to heaven in the mourning over a child; and it becomes a permanent scar in the menopause.” (Calculating by rough computation that a woman menstruates 450 times in her life, the feminist scholar and activist Kate Millett spoke of “a demographer’s nightmare.”)

Medicine’s relative silence about women’s “critical years” may attest to the fact that doctors did not consider menopause a discrete medical problem, but it also indicated ignorance of women’s health issues beyond reproduction. Female physicians, receiving licenses in the United States since the mid-nineteenth century, bemoaned this neglect and demanded more attention for women’s climacteric problems. Yet emerging medical definitions were often ambivalent in their implications about women’s rights.

One of the first Anglophone books on the female climacteric was by Edward Tilt, an English physician, who—like many of his colleagues—had been trained and had practiced in France, in the late 1830s and the 1840s, and imported the idea from there. Tilt described it first in the later chapters of On the Preservation of the Health of Women at the Critical Periods of Life (1851), a small guide for women, as well as in a series of articles. A subsequent, larger book, directed to the medical community, The Change of Life in Health and Disease: A Practical Treatise on the Nervous and Other Affections Incidental to Women at the Decline of Life (1857), was dedicated to the topic entirely. Here, alongside terms such as climacteric and change of life, Tilt introduced the French physicians’ term la ménopause (from the Greek for “month” or “monthlies” and “cessation”), coined by Charles-Pierre-Louis de Gardanne some forty years earlier, originally as ménespausie, to replace the unwieldy expression cessation des menstrues.

Unlike climacteric, the reference to menstruation linked menopause firmly to the female body. Reversing Halford’s findings, Tilt described a change of life that was “insensibly” worked out in men, but “in woman the passage is often perilous and the result is more marked.” He argued that physicians needed to pay more attention to this “crisis,” which he attributed to ovarian “involution” or shrinkage. Tilt’s menopausal patients, presented in numerous case studies, suffered from headaches, felt “giddy and stupid,” feared going mad or losing their memory, and were melancholy and bad-tempered. He compared their condition to hysteria and called it “pseudo-narcotism.”

British literature increasingly used the expression female climacteric from about the mid-1860s, and menopause entered English-language dictionaries in the late 1880s, although it did not become current until the following decade. The new standing of the female climacteric was epitomized in the New York physician Andrew Currier’s The Menopause (1897); an explicit attempt to update Tilt’s work, it was the first monograph by an American physician on the topic.

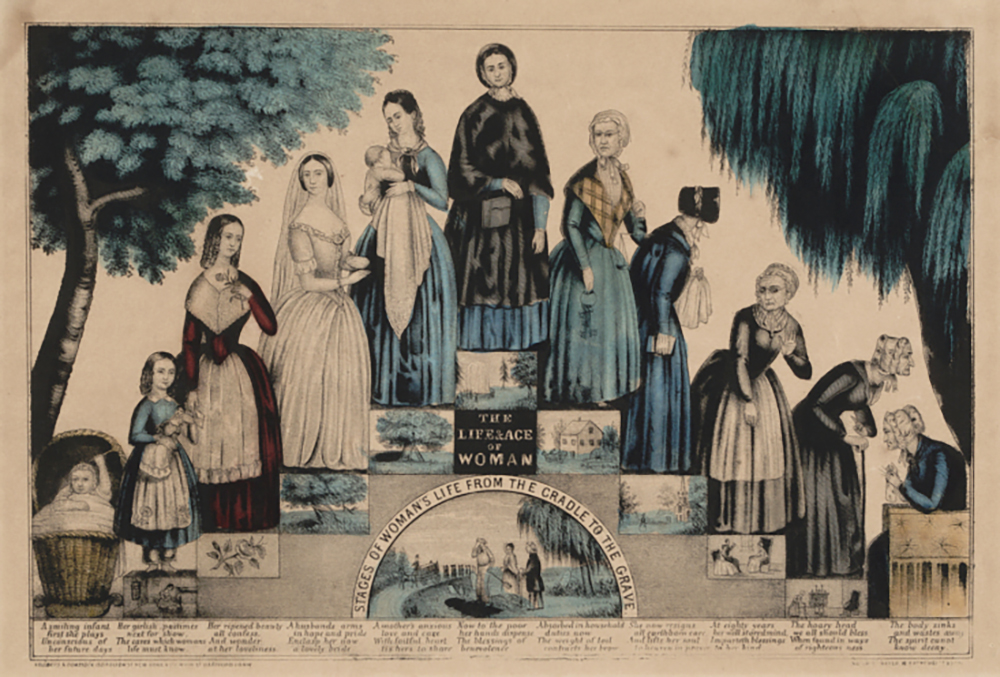

The menopause diagnosis alleviated suffering and made middle-aged women clinically visible as individuals who deserved relief and support. But like many other medical concepts, it also served important social purposes. By linking women’s bodily functions and social roles, reproductive capacity and domesticity, it naturalized a woman’s role as a wife and mother and rationalized the idea that her place was in the home.

As part of the emergence of menopause as a medical category, physicians emphasized the problems accompanying it. Rather than depicting menopause as a normal transition, they described it as an illness in need of treatment or an indication of a body in disorder, a cause of cancer and mental disequilibrium and, not least, a site for expert intervention.

Clinicians were aware of their pathological focus and its limits. Before describing the complications of middle age, Currier, in The Menopause, cautioned that “the majority of women pass through [menopause] with as little incident or discomfort as they experience at puberty. It is only the exceptional woman who has a hard time, and comes to the doctor to tell him about it. Upon this exceptional experience the doctrine of the danger and serious character of the menopause has been built up.” In giving reasons for those problems and suggesting therapies, physicians made the normative and anti-feminist implications of menopause particularly clear: they attributed menopausal problems to women’s violation of social laws.

If menstruation blocked women’s education, then menopause could stymie their careers. Currier spoke for many other physicians when he claimed that menopausal disorders were more serious among those who pursued “unwomanly occupations,” using the example of working-class women in paid work. The menopausal discourse generally focused on the middle and upper classes; the New York gynecologist himself presented menopause as a phenomenon found typically among upper-middle-class women. But medical books sometimes used working-class women as negative examples, to illustrate, for instance, that it was inappropriate for women to take paid work.

Akin to contemporary medical arguments against women’s entry into college, pathological definitions of menopause prevented them from leaving the home, thus constituting a backlash against their advancement in politics and the professions. In typical fashion, Currier asserted that most of his patients experienced menopausal problems—which he displayed as a sign of civilization—but that the “change of life” was less troublesome for “quiet placid” women. Education and a career, attempts at birth control or abortion, failure to devote herself to the needs of her husband and children, advocacy of women’s suffrage, and even a too fashionable, sociable lifestyle were all seen as leading a woman to a particularly difficult menopause.

Correspondingly, middle-aged women—much like their pubescent daughters and granddaughters—were told to avoid mental activities, shun new projects, and commit to domesticity. The recommended regimen for menopausal problems—introspection and careful diet, rest, and plenty of baths—implied withdrawal from society, and confinement was often explicitly advised. Women who did not comply with these prescriptions were mocked for acting inappropriately youthful and warned of a more difficult old age. “We insist,” a women’s guidebook counseled, “that every woman who hopes for a healthy old age ought to commence her prudent cares as early as the fortieth year or sooner…She should cease to endeavor to appear young when she is no longer so, and withdraw from the excitements and fatigues of the gay world in the midst of her legitimate successes, to enter upon that more tranquil era of her existence now at hand.”

But even women who adhered to domestic roles could not avoid menopausal problems. In his 1901 Text-book of Gynecology, Charles Reed, the president of the American Medical Association, was one of the first to emphasize the “mental” aspects of this period of loss for a woman: “She is suddenly brought to perceive that her charms, her youth, her sex itself, are passing from her. She is invited, with cruel abruptness, to be to her husband merely an intellectual companion or a sexless helpmeet, when she had been of late the object of his embraces and the mother of his babes. One third of her adult life is still before her, full of promise of placid enjoyment and great usefulness, but to her, remembering the glory of conquest and surrender, the future stretches a dreary waste of empty years.”

Reprinted with permission from Midlife Crisis: The Feminist Origins of a Chauvinist Cliché by Susanne Schmidt, published by the University of Chicago Press © 2020. All rights reserved.