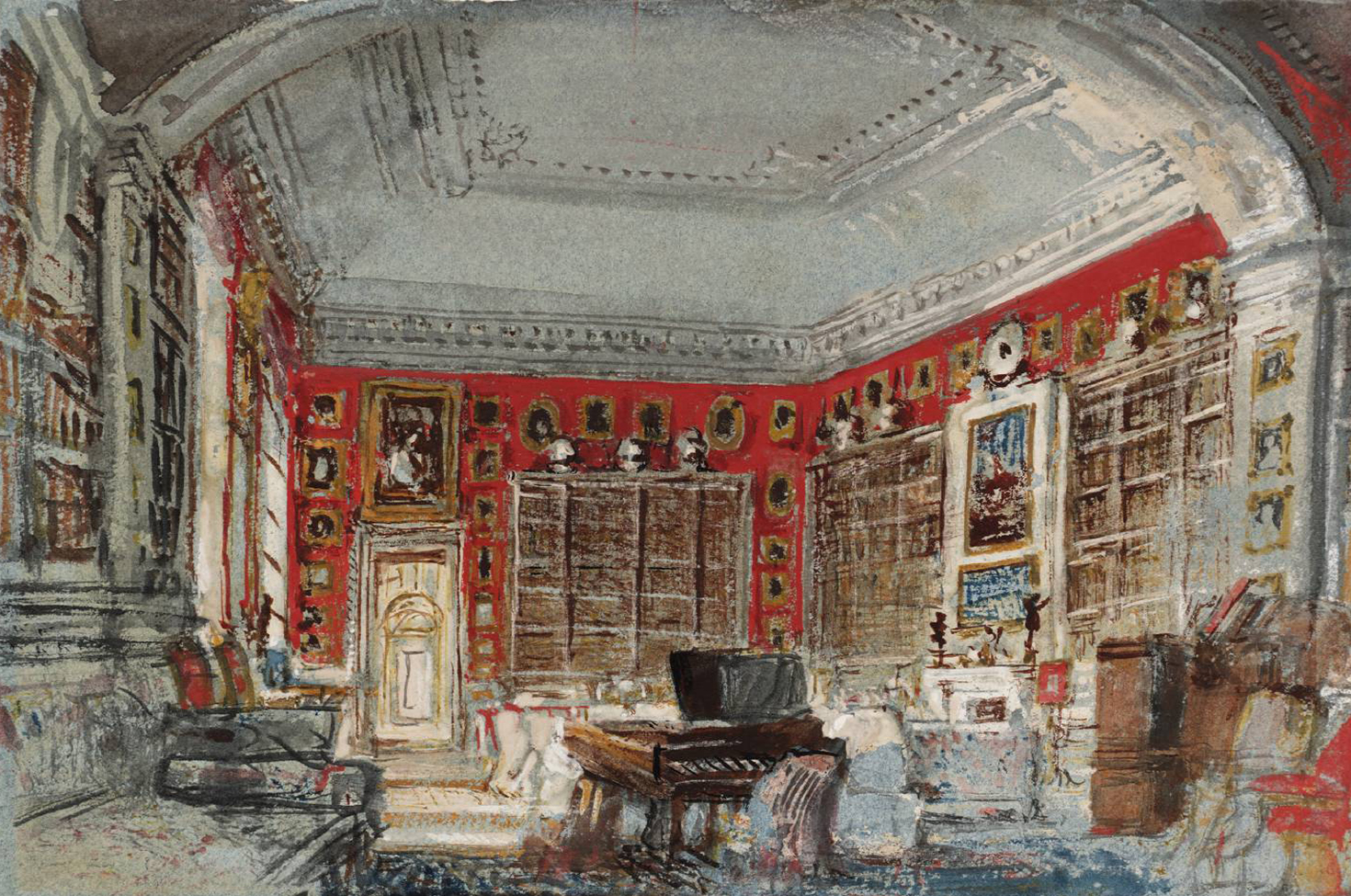

Petworth: The White Library, by Joseph Mallord William Turner, 1827. © Tate (CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0).

For a total of ten months spread over fifteen years, Jane Austen visited her brother Edward Austen Knight at his Kent estate. The brimming bookshelves at Godmersham Park were a particular draw for the novelist. During one stay in 1813—which would turn out to be her last—she wrote to her sister, “I am now alone in the Library, Mistress of all I survey.”

But which books did she survey? Interested parties now have an answer to this question. Chawton House, another of Edward’s manors that now houses a library and research center, and the Burney Centre at McGill University in Montreal have together created a virtual version of Godmersham’s library shelves. The collaboration is called “Reading with Austen.” Users can hover over the shelves and click on any of the antique books, summoning bibliographic data and available photos of pertinent title pages, bookplates, and marginalia. Digging deeper, one can peruse a digital copy of the book and determine the whereabouts of the original.

“What we’ve tried to do really is to imagine Jane Austen actually walking around the library and what she would see in different parts of it,” said Peter Sabor, director of the Burney Centre, who worked on the project for three years. “It’s nice to envisage her looking at those shelves, and, I think, with the website, we can see her do that. We’re basically looking over her shoulder as she looks at the bookshelf.”

There are books of history, travel, religion, literature, and agriculture, as one would expect from a country-house library a couple of centuries in the making. There are surprises, too, mainly in the amount of contemporary fiction, which was largely disdained at the time. Even more noteworthy, perhaps, are the novels by women, such as Maria Edgeworth and Charlotte Turner Smith, that signal the family’s broad-minded reading practices.

The collection’s arrangement is what the Brits would call higgledy-piggledy, as if someone organized it long ago but then gave up. Jonathan Swift, for example, can be found on six different shelves. First editions of four of Austen’s own works are incongruously bookended by The Looker-on, a Periodical Paper, by the Rev. Simon Olive-Branch by William Roberts (1795) and Thinks-I-to-Myself, a Serio-Ludicro, Tragico-Comico Tale by Edward Nares (1812). Northanger Abbey, meanwhile, sits just below with more esteemed bedfellows, Walter Scott and Frances Burney. For anyone with even passing interest in Austen or private libraries, the desire to tab through each volume is hard to resist.

The seed for this project was planted more than fifteen years ago, according to Gillian Dow, executive director of Chawton House Library and associate professor of English at the University of Southampton. In 2010, Dow cowrote an article on the scope of Jane Austen’s reading, which she followed up in 2015 with a piece about the Knight library that proposed reconstituting “digitally—and perhaps physically” the Godmersham Park collection. About five hundred of the original 1,250 titles are at hand, on loan to Chawton, and there is an extant manuscript catalogue of Godmersham’s library, completed in 1818, the year after Austen’s death. With the sustained worldwide interest in Austen, the rise of digital humanities, and—perhaps most necessary of all—funding, the enterprise got off the ground in the summer of 2015 when Sabor arrived at Chawton as a visiting fellow.

The 1818 catalogue, which lists every title in the Godmersham library and its shelf location, helped ensure that each volume would appear on the virtual shelves as it had on Knight’s physical shelves. Determining what the actual shelves looked like was difficult. The Knight family sold the estate in 1874, so the structure had not passed down in untouched condition. Contemporary accounts offer clues but no real visual record. Sabor and his team relied on published descriptions of the library, floor plans, and later photographs. Their rendering, he writes, takes “creative license.” The books had been removed to Chawton House, where Edward’s grandson, Montagu George Knight, cared for them. After he died in 1914 succeeding generations chipped away at the collection, selling some at auction and elsewhere.

While other historical private libraries have been restored through annotated catalogues and searchable databases, the Godmersham initiative transcends even the most innovative among them, like Melville’s Marginalia Online, in terms of appearance and interactivity. The team took inspiration from the 2013 online exhibit “What Jane Saw,” which allowed users to “time travel to two art exhibitions witnessed by Jane Austen.” The Godmersham library project emulates the effect of seeing what Austen saw, except that it is perhaps even more of a moving experience because Austen wasn’t an artist. She was an author and “someone for whom books were very, very important,” as Dow put it. This was not her library—she was poor and had only a handful of her own books—and she certainly didn’t read everything on the shelves at Godmersham (let’s say she skipped the guides to managing a gentry estate). But, as Dow said, “the fact that she had access to them is tantalizing. She’s a writer about whom so very little is known. We think we know a lot, but there are entire periods of her life that are undocumented.”

For Austen scholars, that idea of access to the wider literary marketplace is important in what it might reveal about her and her novels. The library contains some deep cuts in the way of French books and Enlightenment philosophy. “This is someone,” Dow said, “who could reach up, grab a volume of Voltaire, and read it, post-French Revolution—quite a revolutionary thing to be able to do.” The amount of classical literature in translation on the shelves also bolsters the scholarship that sees Greek and Latin roots in Austen’s work; several scholars—including Mary Margolies DeForest, author of Jane Austen: Closet Classicist—argue that Persuasion is Homer’s Odyssey revamped. As a whole, the library helps us imagine a more expansive intellectual landscape for Austen. “I think it gives us a picture of someone who has the capacity to be much more than this kind of closeted spinster in a bonnet that some sectors seem determined to portray her as,” Dow added.

What else might she have pulled off the shelf? If Austen were browsing the center sections along the west wall, she might have happened upon An Enquiry into the Duties of the Female Sex (1797) by Thomas Gisborne, a book she told her sister in 1805 she “had quite determined not to read” until Cassandra recommended it. Surrounded as it is by sermons, the book calls to mind the volume that Mr. Collins recommends to the Bennet sisters in Pride and Prejudice: James Fordyce’s Sermons to Young Women. Conduct literature, as it is called, was known—and pilloried—by Austen indirectly. She figuratively rolls her eyes at Collins, who declares, “I have often observed how little young ladies are interested by books of a serious stamp, though written solely for their benefit. It amazes me, I confess—for certainly, there can be nothing so advantageous to them as instruction.” In her brother’s library, she had several examples of conduct literature to choose from, including Jane West’s Letters to a Young Lady, in Which the Duties and Character of Women are Considered (1811), which looks today as if it had been read by generations of Knight girls. The original survives at Chawton without its binding, held together with white ribbon. “I don’t think she would have been very keen on those ‘duties of women’ and those kinds of books,” said Dow. “Although I’m certain she read them. You can’t lampoon things unless you’ve got a very good working knowledge of them.”

Broadly speaking, it was a gentleman’s library that Knight inherited in 1794. It’s possible that some of the books collected by previous generations—legal treatises or parliamentary records—were barely touched by later Knights. That’s reason enough to be wary of inferring too much from a book’s presence. While it’s no surprise that Samuel Johnson and Shakespeare are well represented, some Godmersham books raise questions: Why did a British landowner buy The American Atlas by Thomas Jefferys, published in 1776, and how did he feel about the American Revolution? Did Austen mine Madame de Graffigny’s Lettres d’une Peruvienne (1747) for marriage plots?

Austen preferred realist fiction, particularly the novels of Frances Burney, perhaps the most famous female author of the time, best known for Evelina, or the History of a Young Lady’s Entrance into the World (1778). Burney’s social satires set her apart from the gothic and sentimental novels otherwise available. Both Austen and the Knights subscribed to her third novel, Camilla, which at the time was a public declaration of one’s literary tastes. (It ought to be on the shelves at Godmersham but has gone missing, one of those losses that illustrates why studying someone’s shelves provides only a partial view of their reading history. Only Burney’s final novel, The Wanderer [1814], appears in the Godmersham inventory.) What else Austen read, either at Godmersham, through the circulating library she joined in Alton, or by other means, can be found in her letters and in references she makes to certain books in her novels. Those books, the ones we know she read, are part of a related exhibition currently on view at Chawton House titled “Jane Austen’s Reading.”

There are other authors’ library re-creations in the works, thanks in large part to what Richard W. Oram, coeditor of the 2014 book Collecting, Curating, and Researching Writers’ Libraries, calls a “robust” interest in the topic, stoked by the emergence of book history as an academic discipline. The venture underway at the Mount, Edith Wharton’s home in Lenox, Massachusetts, is particularly satisfying; it’s the culmination of a story that bibliophiles and Wharton fans have been following for over a decade. After much negotiation, the Mount purchased, in 2005, one of Wharton’s two libraries from a bookseller who had spent fifteen years reconstructing it. The sale price of $2.6 million nearly bankrupted the Mount. When the books were installed on its oak shelves, however, it was hard to dispute that the right decision had been made. Yet in order to make the collection navigable—since you’re discouraged from simply pulling one off the shelf during a house tour and more than half of the books remain inaccessible in attic storage—it would take large-scale digitization. Sheila Liming, assistant professor of English at the University of North Dakota, took up that challenge in 2015. Liming has been working on a digital database that reproduces Wharton’s library, with each volume viewable on a page-by-page basis, so that none of the author’s annotations on her copy of John Donne’s Poems (1669), for example, goes unnoticed. The project is nearly complete.

“Engaging with her books has helped me to see her as a reader and as an autodidact, as opposed to an author in the monolithic sense,” said Liming, whose book on the subject, What a Library Means to a Woman, will be published in December.

Not too far from the Mount, the Emily Dickinson Museum in Amherst, Massachusetts, has also been long at work on an effort called “Replenishing the Shelves.” The poet’s original library was divided between two institutions, Harvard University and Brown University, so her house museum was left without the 2,500 or so volumes that had once filled the Dickinson family homes. Because scholars use those collections for bibliographical research, this attempt to buy the exact editions that Dickinson and her family read is more about context. It portrays the wealth of literature in the house and emphasizes how much reading and book culture shaped the Dickinsons’ lives, according to the museum’s executive director, Jane Wald. So far, they’ve reshelved about five hundred books, mainly nineteenth-century British literature in American editions. George Eliot and Alfred Tennyson appear to have been favorites.

How these reassembled libraries are used—whether to study sources and influences or the more material aspects of the books, e.g., annotations—and what details they may furnish about their users is generally the purview of scholars. But the more inventive approaches welcome amateurs (readers, bibliophiles, literary pilgrims) into the fold, with no expectation beyond rapture. There is something undeniably enchanting about picturing Austen in her brother’s library, “five tables, eight and twenty chairs, and two fires” all to herself, next to a pile of leather-bound volumes that might include Female Biography; or, Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women (1803), Benjamin Franklin’s Experiments and Observations on Electricity (1769), or Ann Radcliffe’s Journey Made in the Summer of 1794, Through Holland and the Western Frontier of Germany (1795). During her final visit, she walked over to the middle of the south wall, bent down to the bottom shelf, and retrieved a triple-decker titled Self-Control by Mary Brunton. Flipping past its beautiful marbled endpapers, Austen reacquainted herself with the novel she had shrugged off when it first appeared two years prior. Writing to Cassandra, she offered this critique: “My opinion is confirmed of its being an excellently meant, elegantly written work, without anything of nature or probability in it.”