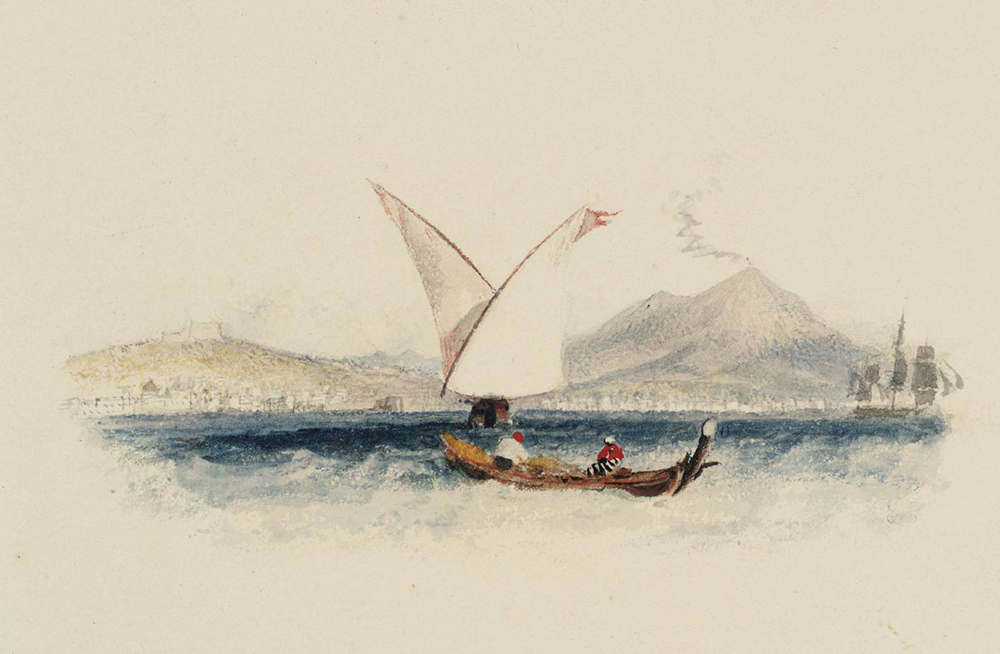

View of the Bay of Naples, by Giuseppe Canella, nineteenth century. Minneapolis Institute of Art, Bequest of Professor Alfred Moir.

In the weeks ahead, as the world continues to reckon with and respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, we will feature voices from the past who told stories that rhyme with the one unfolding before us—stories dealing with quarantine, unfathomable deaths, isolation, dread, and attempts to find community when the rest of the world feels far away.

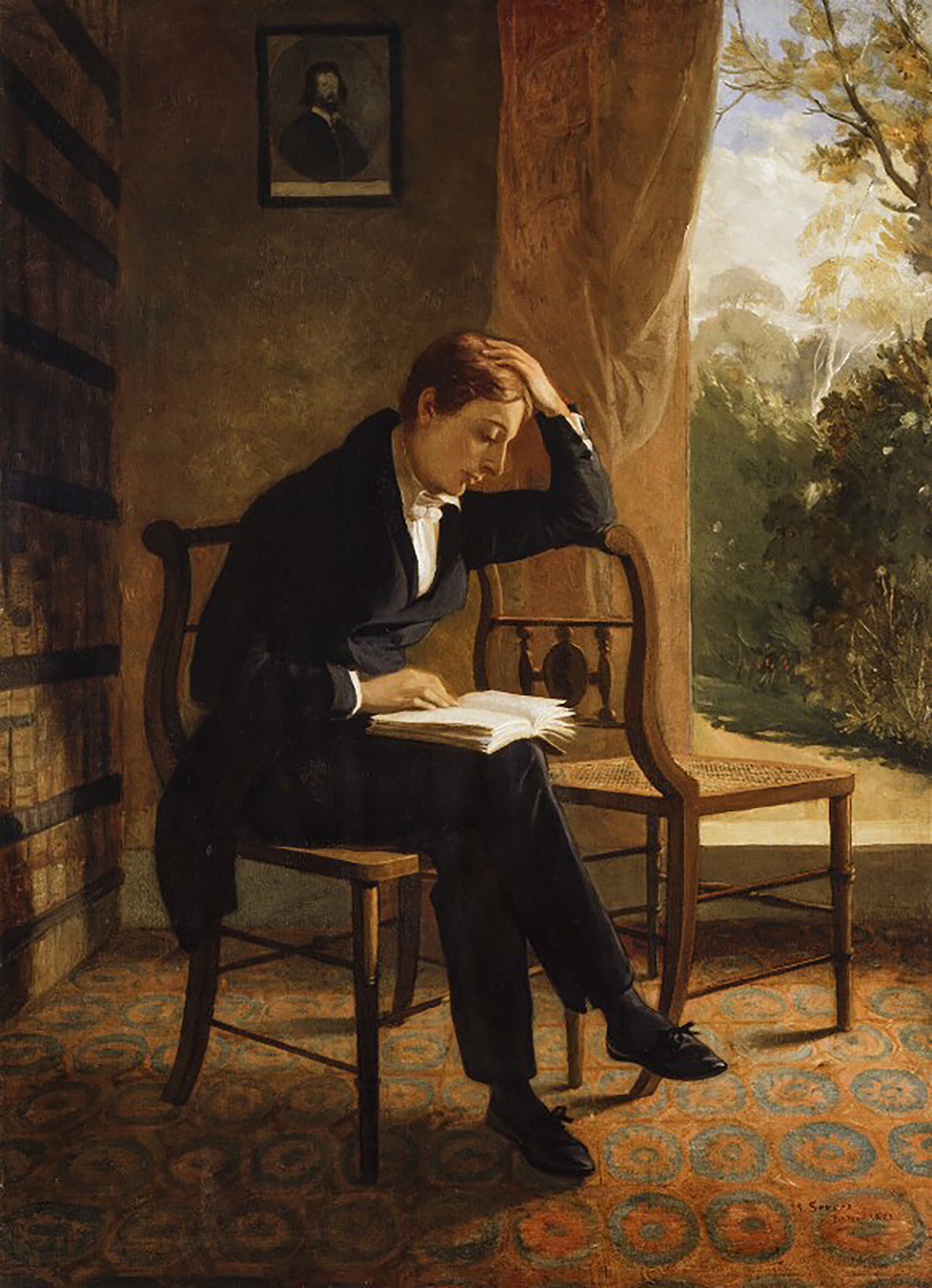

In September 1820 twenty-four-year-old John Keats, along with his friend Joseph Severn, a painter, fled England and headed to Rome, hoping that the air would ease his worsening tuberculosis symptoms. When his ship, the Maria Crowther, reached Naples at sunrise on October 21, an unforeseen ten-day limbo was forced upon him, the ship stuck in the harbor under quarantine. Those on land feared that those aboard had brought the typhus outbreak in London with them. Keats suffered from the discomforts of bad air and digestion and watched the busy traffic of the harbor, tiny ships competing with large ones for space. He listened to the bustle of Naples, the sounds of faraway songs, conversation, and laughter crashing into one another. And, as he later wrote his friend Charles Armitage Brown on November 30, he “summoned up more puns, in a sort of desperation, in one week than in any year of my life.” While quarantined Keats wrote a letter to the mother of his fiancée, Fanny Brawne, sending along a brief message to Fanny that would be his last words to her. And, after leaving the ship and venturing into Naples, he wrote to Brown—who happened to be the Brawnes’ neighbor at Wentworth Place in Hampstead—still fretting over Fanny. Keats died in February 1821, never returning to England.

October 24, 1820

My dear Mrs. Brawne—

A few words will tell you what sort of a passage we had, and what situation we are in, and few they must be on account of the quarantine, our letters being liable to be opened for the purpose of fumigation at the health office. We have to remain in the vessel ten days and are at present shut in a tier of ships. The sea air has been beneficial to me about to as great an extent as squally weather and bad accommodations and provisions has done harm. So I am about as I was. Give my love to Fanny and tell her, if I were well there is enough in this port of Naples to fill a quire of paper—but it looks like a dream—every man who can row his boat and walk and talk seems a different being from myself. I do not feel in the world. It has been unfortunate for me that one of the passengers is a young lady in a consumption—her imprudence has vexed me very much—the knowledge of her complaints—the flushings in her face, all her bad symptoms have preyed upon me—they would have done so had I been in good health. Severn now is a very good fellow but his nerves are too strong to be hurt by other people’s illnesses—I remember Rice1 wore me in the same way in the Isle of Wight—I shall feel a load off me when the lady vanishes out of my sight. It is impossible to describe exactly in what state of health I am—at this moment I am suffering from indigestion very much, which makes such stuff of this letter. I would always wish you to think me a little worse than I really am; not being of a sanguine disposition I am likely to succeed. If I do not recover your regret will be softened—if I do your pleasure will be doubled. I dare not fix my mind upon Fanny, I have not dared to think of her. The only comfort I have had that way has been in thinking for hours together of having the knife she gave me put in a silver case—the hair in a locket—and the pocketbook in a gold net. Show her this. I dare say no more. Yet you must not believe I am so ill as this letter may look, for if ever there was a person born without the faculty of hoping I am he. Severn is writing to Haslam,2 and I have just asked him to request Haslam to send you his account of my health. O what an account I could give you of the Bay of Naples if I could once more feel myself a citizen of this world—I feel a spirit in my brain would lay it forth pleasantly—O what a misery it is to have an intellect in splints! My love again to Fanny—tell Tootts I wish I could pitch her a basket of grapes—and tell Sam the fellows catch here with a line a little fish much like an anchovy, pull them up fast. Remember me to Mr. and Mrs. Dilke3—mention to Brown that I wrote him a letter at Portsmouth which I did not send and am in doubt if he ever will see it.

Yours sincerely and affectionate,

John Keats

November 1, 1820

My dear Brown—

Yesterday we were let out of quarantine, during which my health suffered more from bad air and the stifled cabin than it had done the whole voyage. The fresh air revived me a little, and I hope I am well enough this morning to write to you a short calm letter;—if that can be called one, in which I am afraid to speak of what I would fain dwell upon. As I have gone thus far into it, I must go on a little;—perhaps it may relieve the load of wretchedness which presses upon me. The persuasion that I shall see her no more will kill me. My dear Brown, I should have had her when I was in health, and I should have remained well. I can bear to die—I cannot bear to leave her. Oh, God! God! God! Everything I have in my trunks that reminds me of her goes through me like a spear. The silk lining she put in my traveling cap scalds my head. My imagination is horribly vivid about her—I see her—I hear her. There is nothing in the world of sufficient interest to divert me from her a moment. This was the case when I was in England; I cannot recollect, without shuddering, the time that I was a prisoner at Hunt’s, and used to keep my eyes fixed on Hampstead all day. Then there was a good hope of seeing her again—Now!—O that I could be buried near where she lives! I am afraid to write to her—to receive a letter from her—to see her handwriting would break my heart—even to hear of her anyhow, to see her name written, would be more than I can bear. My dear Brown, what am I to do? Where can I look for consolation or ease? If I had any chance of recovery, this passion would kill me. Indeed, through the whole of my illness, both at your house and at Kentish Town, this fever has never ceased wearing me out. When you write to me, which you will do immediately, write to Rome (poste restante)—if she is well and happy, put a mark thus +; if——

Remember me to all. I will endeavor to bear my miseries patiently. A person in my state of health should not have such miseries to bear. Write a short note to my sister, saying you have heard from me. Severn is very well. If I were in better health I would urge your coming to Rome. I fear there is no one can give me any comfort. Is there any news of George? O that something fortunate had ever happened to me or my brothers!—then I might hope,—but despair is forced upon me as a habit. My dear Brown, for my sake be her advocate forever. I cannot say a word about Naples; I do not feel at all concerned in the thousand novelties around me. I am afraid to write to her—I should like her to know that I do not forget her. Oh, Brown I have coals of fire in my breast—it surprises me that the human heart is capable of containing and bearing so much misery. Was I born for this end? God bless her, and her mother, and my sister, and George, and his wife, and you, and all!

Your ever affectionate friend,

John Keats

1 Keats had spent a month with his ailing friend James Rice the year before. ↩

2 William Haslam was another member of Keats’ circle of friends. ↩

3 Charles Wentworth Dilke and his wife Maria also lived at Wentworth Place. ↩

Read the other entries in our series: Heinrich Heine, George Eliot, Samuel Pepys, Willa Cather, Lucretius, Thomas Mann, Jack London, Alessandro Manzoni, Giovanni Boccaccio, Frances Hodgson Burnett, Daniel Defoe, François Rabelais, and Robert Louis Stevenson.