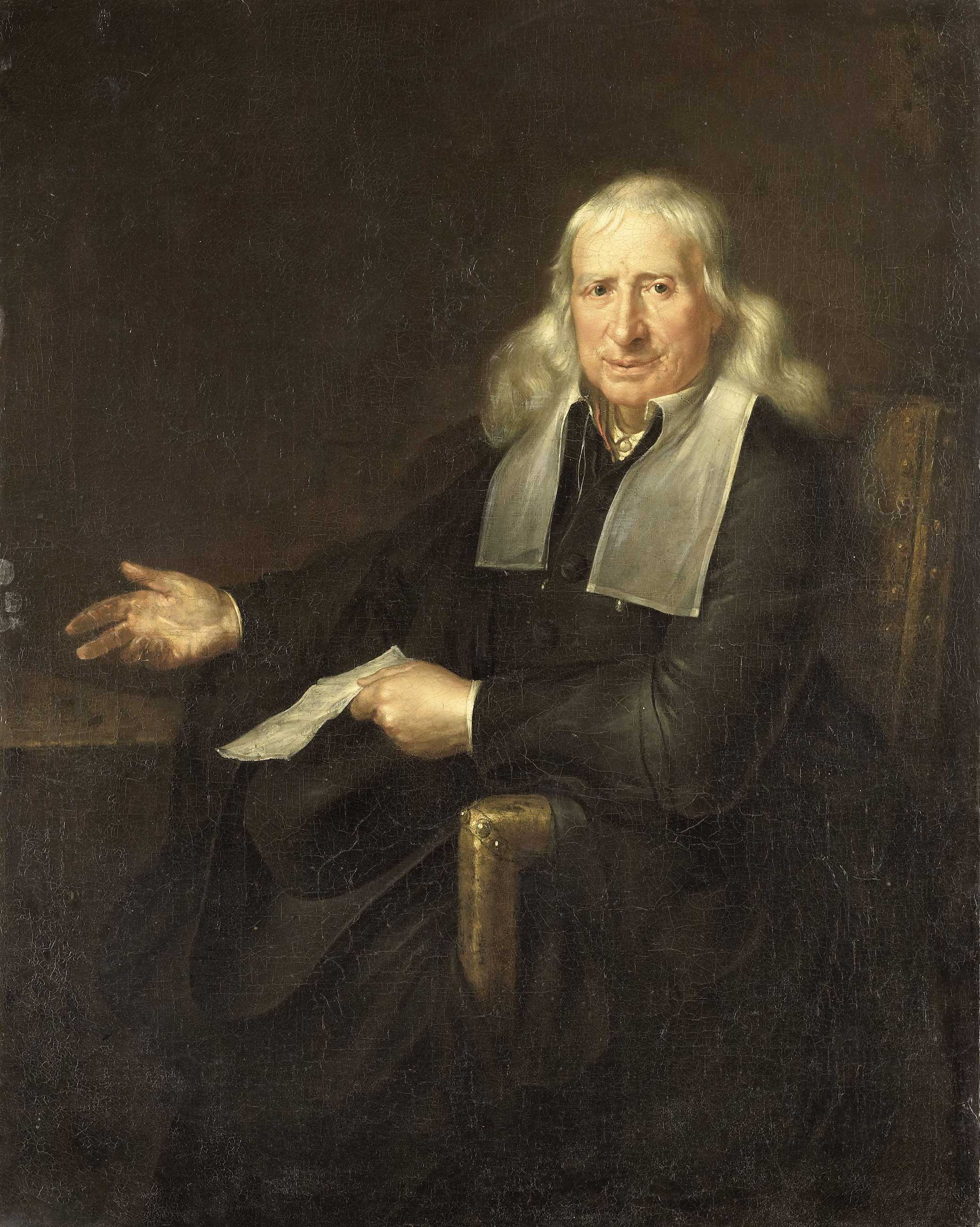

Portrait of Jan van Lennep the Elder, Amsterdam Merchant, c. 1700. Rijksmuseum.

Writing, accounting, and expertise were all sought-after skills in English merchants conducting trade abroad in the sixteenth century, and all employees in this role would be expected to hold at least some level of competence in each of them. Something that could really set applicants apart was knowledge of languages.

Business was conducted in multilingual and cross-cultural environments and the need to communicate with merchants, manufacturers, brokers, and officials in markets across the world meant that mastery of languages, or even competence, was in great demand. Finding merchants able to operate in these different linguistic environments was not always easy, especially in trades where English was never likely to be helpful. The East India Company, for instance, was reliant on Spanish- and Portuguese-speakers to engage with Asian rulers, and “Richard Temple who had the Spanish tongue” was propelled to a position of great importance when he was appointed to act as an interpreter between Paul Canning and the Mughal emperor Jahangir in Agra.

Demonstrating the effective application of language in a business context, usually learned while merchants were living abroad during their training, could be a surefire way of obtaining a position. In the case of Mr. Brund, a merchant initially overlooked by the East India Company for the post of principal factor—or trade agent—his linguistic expertise was so widely admired that the corporation’s members protested the decision. Insisting that Brund was “a grave and discreet merchant and one which hath the Arabian, Spanish, and Portugal languages,” they argued that his exclusion could only mean the directors themselves misunderstood the demands of the trade. In the face of a linguistically fueled shareholder rebellion, Brund’s appointment was quickly confirmed at their next meeting.

Languages were held in such high regard due to their scarcity, and making sure that would-be traders really had the necessary skills to conduct negotiations in another tongue was not always easy. For example, when the East India Company sought to employ “writers skillful in the Dutch tongue” as representatives in the United Provinces, they were so disappointed by the initial applications that they sent a subsequent applicant, Edmond Baynham, a test to ascertain the quality of “his writing and speaking Dutch.”

Where possible, merchants sought to train skilled linguists from among members of their community. Efforts were made to provide instructional texts, such as William Strachey’s “dictionary of the Indian language for the better enabling of such who shall be thither employed” and Richard Hakluyt’s material for learning the rudiments of the Malay language that the East India Company thought would be “very fitting for their factors,” but these were probably not all that helpful. Companies tended to rely on language learning during apprenticeships instead, as this could be validated more easily through recommendations. For instance, John Major was apprenticed to John Guillam “to be instructed in the said art [of a merchant] and the French tongue.” Similarly, in order to obtain a loyal and English, but linguistically capable administrator for their activities in the Ottoman Empire, the Levant Company considered “whether it was not meet to breed up an Englishman in the ambassador’s house [in Constantinople] to be the secretary after Signor Dominico.” Other merchants obtained language skills and experience of living in different lands through less structured educational experiences. The London merchant Lewes Jackson, for instance, who left England in the Little Hopewell “bound for the Amazons,” found himself diverted to “Wyapoko” where he stayed for fifteen months before returning to England via Barbados.

Linguistic skill was respected, but it was the ability to communicate effectively that was essential for early modern merchants—and this was not just a matter of language. It was with this in mind that George Best wrote a detailed account of his travels to North America, offering advice about “how to proceed and deal with strange people” and detailing the ways “trade of merchandise may be made without money.” In different contexts, working with and accepting local commercial practices was important, such as in Massachusetts where Richard Foxwell “do cause myself to owe and stand indebted unto Francis Johnson” not cash but “one hundred twenty and five pounds of good marketable beaver.” It did not matter if these practices were not the ones merchants might have learned in England; when working in overseas markets, it was a merchant’s job to adapt and get the job done.

Unclear communication between merchants could have deleterious effects on both personal relationships and the effective execution of trade. Thomas Kerridge and Mr. Brown, two traders in India, were deeply frustrated by their colleagues in Surat who failed to respond to their detailed, clear letter in kind, instead returning one full of “many good words almost past our understanding.” The accused party had chosen “to enjoy the license poetical,” which was entirely unhelpful given that Kerridge and Brown had “no Latin” and were “unacquainted with the language.” While in this instance poor communication mostly just annoyed their colleagues, a similar failing by an East India Company employee had much more chaotic effects. In 1636 one observer, with some delight, wrote a “good tale” about how “a merchant of London that wrote to a factor of his beyond the sea” was undone by his own poor handwriting. While the merchant had “desired him by the next ship to send him ‘2 or 3 apes,’ he forgot the ‘r’ and then it was ‘2 o 3 apes.’ His factor has sent him four score and says he shall have the rest by the next ship, conceiving the merchant had send for two hundred and three apes!” Quite what a spectacle the arrival of a troop of apes at London’s waterside might have caused has not been recorded, but the story, which the author claimed “in earnest…is very true” highlights how even the smallest error might lead to quite unexpected consequences.

Agreeing to work for a merchant, join a company, or enter an apprenticeship meant agreeing to abide by the expectations of the commercial community regarding good mercantile behavior, as well as following the specific orders that your employer, corporation, or master might issue. This was reflected in contractual agreements and social efforts to enforce standards. In the Eastland Company, any sons, servants, or apprentices deemed disorderly could immediately be dismissed from service; while the young William Harte lived under threat that if he was “obstinately disobedient” or did not “fully and duly fulfill the whole term of his service,” he would lose out on a £500 inheritance. Other factors operated under conditions specified in bonds, whereby they would forfeit a specified sum of money if they failed to undertake business as instructed. In the East India Company, upon their appointment, factors would “give in bonds for their truth and good behavior” that ranged from £500 for the first level of factors who would lead the expedition to 100 pence for the most junior fourth sort of factor.

When regulations and orders were not followed, corporate oversight meant that perpetrators were quickly disciplined—whether overseas or in England—and fines, dismissal, and imprisonment were all common punishments. For example, during a concerning string of napkin thefts from the Mercers’ livery company, its directors initially concluded that the butler did it, but after further investigation discovered that one Oliver Cogram was the culprit, and “he was dismissed from the service of the company.” Samuel Grosse faced worse punishment after he committed fraud in Great Yarmouth, and having “counterfeited the town’s best brand of herring,” the offending trader was immediately imprisoned. Another merchant, William Craddock, was apprehended while transporting 270 kerseys (coarse woolen cloths) from London to Hamburg and on to Middelburg by the “Society of Merchant Adventurers there residing,” who accused him of trading contrary to the company’s charter. To Craddock’s great disgust, he was “imprisoned in the common gaol among felons and criminal offenders,” where he would wait until he had paid £180. Senior merchants were not immune either. When John Robinson was found “in contempt of the good rules and ordinance of his said company and of this city” after refusing to act as warden in his livery company, the City of London had no qualms about imprisoning him at Newgate “until he shall conform himself.”

Failing to meet the behavioral standards of the community was similarly a punishable offense. In Southampton, the port’s corporation chastised Thomas Jackson “about certain reproachful and slanderous words which his wife should speak unto Mr. Dalby against Mr. Nevey and his wife.” Similarly, Daniel Veale was fined seven pence after he “called the said John Bigges knave,” an uncivil action “contrary to the ancient orders and customs of this town.” In London, in one dramatic instance, during a dispute over a cart, William Merrick “with the help of others his assistant” had “assaulted the said Master and Wardens of his company,” threatening “to draw his knife upon them, and through violence and by force took the cart away from them.” The incident was reported to the City of London and Merrick was imprisoned in Newgate. Worse still, when Edward Beadle, the apprentice of Humphrey Clarke, was caught acting “very insolently and contemptuously against the authority of the Lord Mayor,” vandalizing city proclamations with “a picture of a gallows and of a man hanging on the same, and also used unfitting speech,” he was whipped as punishment.

When a servant of Stephen Thomson complained about his master “for hard usage, namely by keeping him in prison” for three weeks, he was in turn condemned for “misspending of his goods, from absenting himself from his service, for lying out of his house,” and, worst of all, “for keeping lewd women’s company.” After a long debate, the Clothworkers’ livery company’s directors agreed that the servant should “submit himself to his said master, acknowledge his faults, and ask forgiveness of him for his lewd behavior.” Their only request of Thomson was that in future he bring his complaint to the company first before imprisoning his servant. It seems likely, in this circumstance, that the “lewd” behavior of the servant was a deciding factor in the company’s justification of his punishment—such activity could reflect badly on the whole society.

Ensuring members did not damage the corporate relationship with local actors meant strict measures were taken against members who acted poorly while overseas. Members of the Merchant Adventurers were discouraged from playing “either at dice or cards or tables,” and gambling in public elicited large fines. They were further forbidden to fight or quarrel “(except in his own defense) with any stranger,” and here, too, the punishment was sizable; a freeman of the company would be fined £20 and servants and apprentices banned from practicing the trade overseas for three years and only readmitted after paying a fine of £100. Beyond offending local sensibilities and damaging commercial relationships, immoral activities were also seen as a direct cause of bad business.

Thus, in response to what was likely a widespread practice, the Merchant Adventurers enacted a rule that none of their members “use unreasonable or excessive drinking” to provoke others to pledge. In a similar vein, the company combated the temptations many members might have felt, living for years or decades overseas, by insisting “no married man of this fellowship shall keep or hold any harlot, light or evil disposed woman, or abuse himself with any such.” If a married member was caught three times in this position he would be expelled from the company. Unmarried members would not be expelled but would face fines increasing with each offense “and be further punished at the discretion of the court.” Any merchant who dared go further and actually “married a foreign woman” was immediately disenfranchised from the company. In this case, it was not the threat of offending the host community that concerned the company, but the risk of the merchant joining it.

Excerpted from Merchants: The Community That Shaped England’s Trade and Empire, 1550-1650 by Edmond Smith. Copyright © 2021 Edmond Smith. Reprinted by permission of Yale University Press.