Elephant from Mysterious Asia concession in Pikers Parade on the opening day of the 1904 World’s Fair, 1904. St. Louis Public Library, Louisiana Purchase Exposition glass plate negative collection.

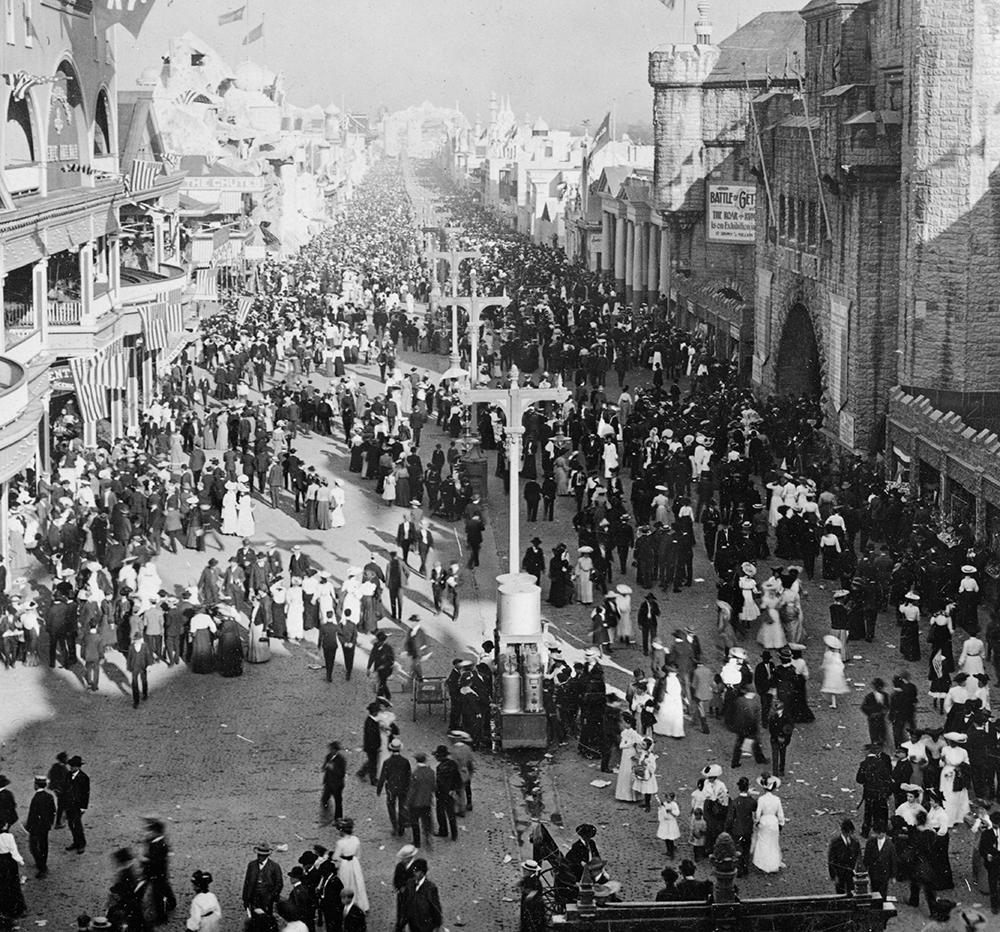

The 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis is remembered by some as the high-water mark of the city’s history—the moment when all the world was assembled in tribute to the city’s greatness, the moment at the crest of the rise, before the beginning of the long decline. Termed the Louisiana Purchase Centennial Exposition, the 1904 World’s Fair celebrated the “civilization” of the continent. And on that legacy of conquest, it founded a vision for the coming century—modern, technological, commercial, imperial, American.

“The Babylon of the New World,” the civic booster and impresario of the move-the-capital-to-Missouri movement Logan Uriah Reavis termed St. Louis at the turn of the century. And indeed, in its ambition, scope, and arrogance, the fair was a Babylonian gathering-in of all the peoples, things, and knowledge of the known world, a vast imperial harvest. But the comparison was double-edged, at least for anyone who had read the Old Testament. For St. Louis at the turn of the century was more like the Babylon remembered by the Israelites: presenting itself to the world in the splendor of its boundless ambition, but rotten at the core.

The city’s own imperial history and aspirations framed the fair. The discipline that presided over the fair was neither psychology nor sociology, nor even physics, but anthropology. Like the rest of the exhibits on the grounds—like the baby incubators on the midway (“the Pike”), the miniature railways, the motorized airships, the X-ray machine, and the world’s first air conditioner and player piano and cordless phone and wall plug and fax machine and answering machine—the world’s intellectuals were self-consciously positioned by organizers to make a point about history and civilization.

The purpose of the fair, in the words of David Francis, the chief executive of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition Corporation, was to demonstrate to visitors that human history had reached its “apotheosis” in Forest Park. Were all the works of prior civilization to be blotted out, he concluded, the records of the fair would provide the “necessary standards” for its rebuilding.

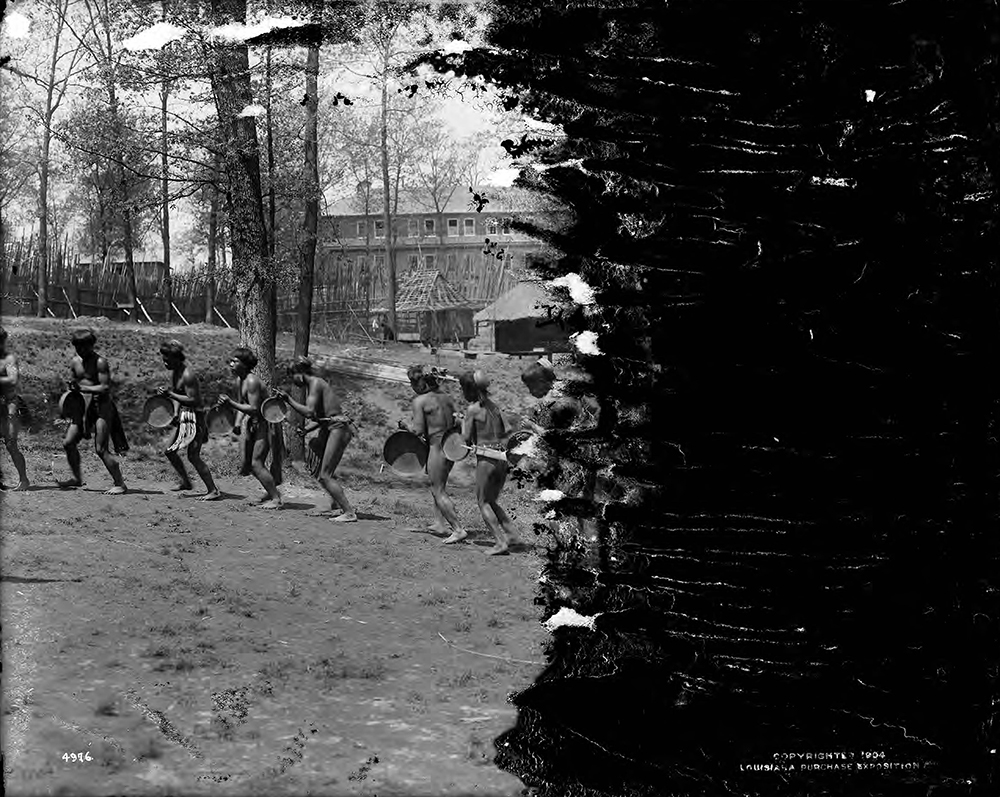

In Forest Park in the summer of 1904, the directors of the exposition’s Anthropology Department, including the founder of American cultural anthropology, Franz Boas, presided over the assembly of the largest human zoo in world history. An estimated ten thousand people were conscripted to play a role in the account of progress by the Anthropology Department. Brought to St. Louis for the fair, they lived for its duration on the grounds and were exhibited in ersatz reconstructions of their “native habitats” for curious visitors to Forest Park. Among them were Ainu people from Japan, “Patagonians” from the Andes, and members of fifty-one of the First Nations of North America—including Chief Joseph of the massacred Nez Perce, the Comanche soldier Quanah Parker, and the Apache leader Geronimo. Geronimo was assigned to pose for nickel-apiece souvenir photographs with white visitors and play the part of the Sioux leader Sitting Bull in daily reenactments of the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Elsewhere on the grounds lived Ota Benga, who had been sold along with seven other people to the American Samuel Verner, who had traveled to King Leopold’s Congo Free State under the auspices of the fair’s Anthropology Department to purchase Mbuti “pygmies” with the sole purpose of exhibiting them at the fair. Benga, who was about twenty at the time of his sale, had had his teeth filed into sharp points as a child, and was exhibited at the fair as a “cannibal.” Benga and the other enslaved Africans sometimes danced and performed before as many as twenty thousand people at a time. For a time after the fair, under the auspices of the white supremacist racial theorist Madison Grant, Benga was kept in a cage at the Bronx Zoo. After his release, Benga worked in a tobacco factory in Virginia, where he began to wear Western clothes and had his teeth capped. In March 1916, in Lynchburg, Virginia, Ota Benga built a large fire, danced, and then shot himself through the heart.

The historical record of the fair tells us much more about people like David Francis and Franz Boas than it does about people like Geronimo and Ota Benga.

The forty-seven-acre “Philippine Reservation” in the southwest corner of the fairgrounds was the 1904 fair’s ideological core as well as its most popular attraction—ninety-nine out of a hundred visitors to the fair visited the reservation, estimated Francis. Although the U.S. war against the Philippines had officially ended in 1902, American troops were still fighting insurgents on several of the islands of the Philippine archipelago. The Philippine exhibit in St. Louis was, at once, a celebration of conquest, an operation in an ongoing counterinsurgency campaign, and an argument about why the first two were necessary actions taken in the support of racial civilization and social progress. The War Department, with the support of William Howard Taft, the U.S. military governor of the Philippines, coordinated the collection and transport of the one thousand eventual inhabitants of the Philippine Reservation, as well as of the battalion of Philippine Scouts—four hundred U.S.-aligned Filipino soldiers, who served under white officers. The fair, Taft argued, would exert “a very great influence on completing the pacification of the Philippines” by creating a cadre of Filipinos who would be informed about the wonders of modern civilization and overawed by its inexorability. The Philippine Reservation was, one could argue, a civilizationist psyop—an act of psychological warfare.

That the Philippine Reservation was called a “reservation” in the first place reflected an important fact about the racial imagination of the fair organizers. In their view, the specific imperial history of the American West—the history that began with the Lewis and Clark expedition—provided the model for the future of the American empire and the world more generally. The legacy of conquest was celebrated throughout the park, in both the massive statuary of noble savagery— Cyrus Dallin’s Sioux Chief being exemplary in this regard—and the daily restaging of the Battle of the Little Bighorn. But the overriding message of the fair was about consigning the “savage” past to the future progress of “civilization.”

There was no room at the fair for a story about African American racial progress. The very same black soldiers who had served as imperial adjutants in the Indian wars, the Spanish-American War, and the Philippine-American War—which were endlessly replayed as the historical backstory of the 1904 fair—were not allowed on the grounds in uniform. All of the fairground restaurants were segregated. Plans for a building celebrating the advances and achievements of American blacks were broached but never materialized. The plan for a single “Negro Day” at the fair was eventually canceled, and a speaking invitation to the ex-slave, educator, and up-by-your-bootstraps conservative Booker T. Washington was withdrawn. The only representation of African Americans on the fairgrounds was at the “Old Plantation,” where black actors tended a garden, staged a fake religious revival, sang minstrel songs, and cakewalked in an endless loop of white racial nostalgia.

The fair provided many opportunities for visitors to insert themselves into its overarching account of racial time. They could, in time-honored fashion, gawk and chuckle at the way other people in the world lived; they could even riot when those other people refused to perform for them, as happened when the crowds threw rocks at the small houses in which Ota Benga and his fellows took shelter when the weather got cold. The rumor that some of the denizens of the Philippine Reservation ate dogs provided one of the most durable memories of the fair in St. Louis. To this day one of the neighborhoods near the long-gone exposition grounds is called Dogtown, because it is supposedly where the Filipinos got their dogs.

In a city where one-fifth of the population was foreign-born and twice that many again had parents who were, the fair offered a powerful argument about the solvent character of imperial whiteness. It offered a dirty bargain to the working whites in a city with an enduring strain of labor radicalism: over two hundred stoppages and strikes had disrupted the preparations for the fair, and a property-protecting posse of hired guns in the service of capital had opened fire on a workingmen’s parade only four years earlier. Come spend a day enjoying yourselves, the fair beckoned; lay down your placards and your pistols, and take up your rightful place in the front rank of civilization and the “march of progress.” The fair exhibits were designed to domesticate the restive immigrant workers of St. Louis by turning them into white people.

Adapted from The Broken Heart of America: St. Louis and the Violent History of the United States by Walter Johnson. Copyright © 2020 by Walter Johnson. Available from Basic Books.