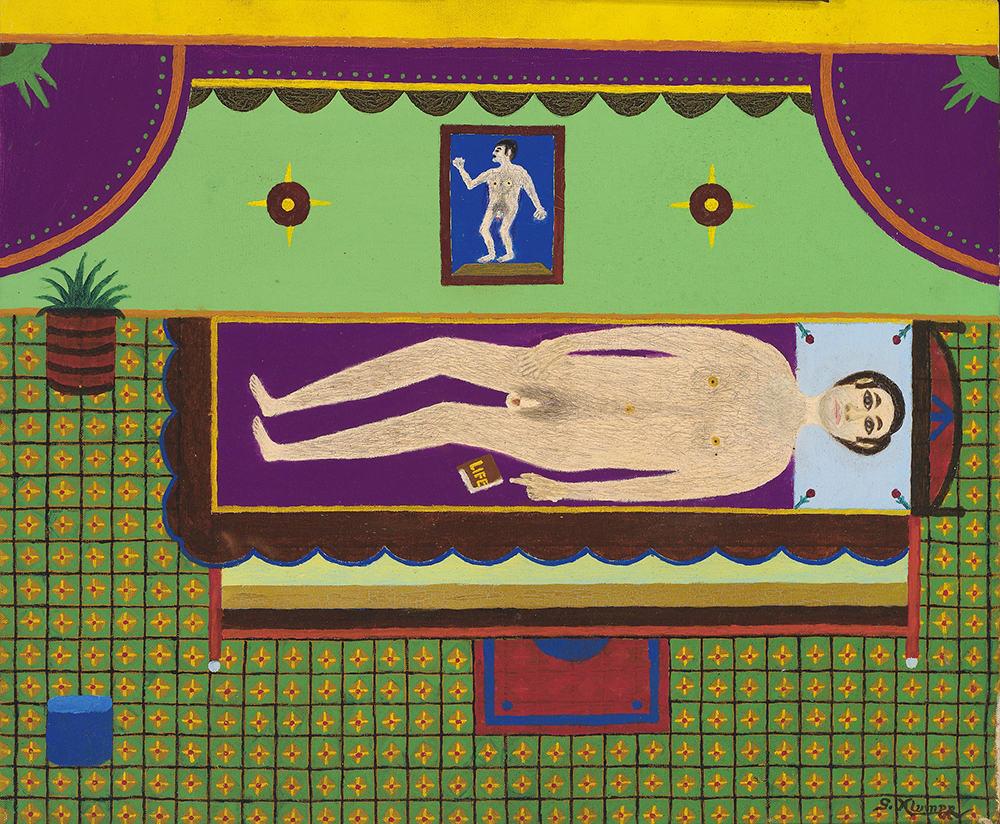

Male nude figure, c. 650 bc. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of Martin and Herbert Orenstein.

American nudism, and the free and natural lifestyle of which it was a part, grew out of Lebensreform (or “life reform”), a mid-nineteenth-century German health movement that encouraged urban dwellers to address the ills of industrial society by living more naturally. Nudist philosophy, which was referred to by British practitioners as naturism, and by Germans as Nacktkultur, included vegetarianism; exposure to fresh air, water, and sunlight; abstinence from tobacco and alcohol; and back-to-nature activities like gardening, hiking, and camping. To explain social nudism to American audiences and study the therapeutic possibilities of group nudity, Howard C. Warren, a professor of psychology at Princeton, published a widely circulated essay in 1933 in which he described his stay at the German nudist camp Klingberg, near Hamburg. Klingberg was owned by Paul Zimmerman, who had purchased the property in 1902, in social nudism’s very early years, and had raised his family according to the principles and protocols of the emergent body culture. Warren concluded that nudists were not “radicals, social rebels, or faddists,” nor would he characterize them as “perverts or neurotics.” Instead, everyone was relaxed, “natural, and unconstrained.”

Frances and Mason Merrill, a young couple from New York, had visited Klingberg two years earlier and feared that nudism could never take hold in the United States. In their 1931 work Among the Nudists, the Merrills argued that there would always be strong social, economic, and political pressures opposing progressive body politics, ranging from the Protestant prudery of American social reform movements to the Ku Klux Klan’s xenophobia. Not only would nudists appear inherently indecent, but their cultural practice had foreign origins. Trying to take a more optimistic tack, the Merrills also noted that despite American social conservatism, there were “certain factors in American life that might favor the progress of the [nudist] movement. The most obvious is the popularity of sunbathing in recent years. During the past few summers, whether seeking health or merely a fashionable ‘sun tan,’ countless Americans have been toasting themselves.” But the widespread popularity of suntans in the 1920s and 1930s was not symptomatic of a broader social movement; rather, the intentional suntan was tightly connected to a consumer economy directed toward a new youth market with money to spend on outdoor activities and ready-made clothing like the swimsuit and the backless sundress. Suntans signified leisure and wealth, not socialism or social experimentation.

Mulling over the naturist legacies of Whitman and Thoreau, the Merrills concluded in their second work, Nudism Comes to America, that the only future a nudist movement really could have in America was one of individual rather than social conviction, practiced in small, atomized groups. The Merrills believed that rather than in the countryside, as in Germany, American nudism would be better suited to cities.

Urban nudism would prove more challenging than the Merrills had thought. In 1931 Kurt Barthel, the German immigrant who transplanted social nudism to the United States when he founded the American League for Physical Culture in 1929 in New York, quickly foundered when he tried to organize urban events for his membership. After renting a gymnasium and swimming pool for a nude social gathering, league members found themselves promptly arrested and hustled into police vans under the watchful eye of the female neighbor who had called it in. Similar incidents ensued, and American nudists began to take refuge in the very countryside naturist theorists had suggested they avoid. In case nudists dared to move back to the city, already driven out by police raids on gymnasia and private homes, charges of indecent exposure, and the humiliating news reports that listed their names and addresses, the legislature in Albany, New York, passed the nation’s first anti-nudism law in 1935.

American nudism went on the offensive, and in 1931 Kurt Barthel, Ilsley Boone, a Baptist minister, and a mutual friend, David Livingston, laid out the proofs for The Nudist, a short and rather primitive magazine featuring a nude image on its cover and copies of newspaper clippings covering the league’s legal battles with the New York City courts. It clearly made for good reading, and The Nudist soon had subscribers in the thousands who enjoyed wholesome, often airbrushed, images of naked sports, nude camping, and other back-to-nature exploits along with lengthy treatises about the importance of the sun for optimal health. The original issues of The Nudist often featured mixed-gender groups on their covers, avoiding any suggestion that it might be a girlie magazine, with the bodies crouched or turned in such a way as to cover their genitalia. The implication was that nudism was serious business, with potential for fun, but an activity more akin to labor than leisure. On the cover, for example, a group of nudists have hiked to the lakeshore where they are shown resting after shedding their shoes; this is no simple stroll from their hotel to the beach.

Barthel then expanded the opportunities for free and natural living in April 1932 by purchasing property in Liberty Corner, New Jersey, to establish Sky Farm, the first nudist camp in the country and a member-owned cooperative. Shortly thereafter, Boone established his own camp, Sunshine Park, in Mays Landing, New Jersey, which would become the East Coast anchor for organized nudism while his press, the Sunshine Book Company, published The Nudist, establishing it as the movement’s flagship magazine.

With the creation of the camps, the magazine, and the newly constituted International Nudist Conference (INC), organized nudism took off and inspired the founding of clubs and camps all over the country, including Ohio, Michigan, California, and New York. By 1933 The Nudist listed forty-four clubs and over three hundred card-carrying members of the INC.

Reflecting the legal danger of having nudism and sex associated in the popular imagination, in 1936, at the Fifth Annual Meeting of the INC, held in Valparaiso, Indiana, the membership elected to change the organization’s name from the International Nudist Conference to the American Sunbathing Association (ASA) and the title of the magazine to Sunshine and Health to distance themselves from the word nudist, which had increasingly taken on eroticized connotations in popular culture. In a published statement, members explained that “no sooner had the nudist movement in this country succeeded in fixing the connotation of the words nudist and nudism than these terms were seized upon by burlesque theater managers, night club troupes, disorderly roadhouses, and exposition sideshows to further their own business enterprise in the field of commercialized pornography.”

It seems likely, too, that the political connotations of the words International Nudist Conference, with possible links to things foreign and leftist, may have inspired the name change. It is certainly plausible that the terms international and conference evoked too strongly political organizations subject to congressional scrutiny as subversive, as well as evoking German Nacktkultur, which, by the mid-1930s, was entirely, and inaccurately, associated with the Third Reich. By 1936 the INC had taken great pains to separate itself from German nudism as Hitler had decimated that country’s nudist groups because of their leftist working-class egalitarian politics, replacing the physical culture of socialist nudism with the body cultism of fascist Aryanism.

American nudists may have distanced themselves politically from both fascism and socialism, but they could not sidestep racism. American nudist ideology in the 1930s retained disturbing echoes of eugenics, with The Nudist publishing essays on selective breeding, describing how nudist mothers raised stronger children (due to early childhood sun exposure), or asking “can we develop a race of super-men?” Maurice Parmelee, a sociologist, political theorist, founder of American criminology, and early adopter of nudism, while committed to fostering an egalitarian society that embraced both feminism and racial equality, had trouble reconciling his intellectual sympathies with the eugenic concepts of biological determinism and social evolution about which he published and taught while a faculty member at the University of Missouri.

In his 1931 treatise, Nudism in Modern Life, Parmelee outlined his theory of how the widespread practice of nudism (what he called “gymnosophy”) would unite people worldwide and reinforce the democratic, egalitarian, and humanistic ideals he held dear. While ascribing cultural norms to biological race, an understanding of human difference in line with eugenics theory, Parmelee emphasized that what one considered a natural or beautiful body was subjective. For example, he argued that “our standards and ideals of human beauty are determined largely by the fundamental human type, by the racial type to which we belong, and for each sex by the sex type. With respect to the beauty of these types there can be no argument, for they are the types to which we are accustomed, and which are natural and normal for us. Such statues as the Aphrodite of Melos and the Doryphorus of Polycleitus…are generally regarded as beautiful because they conform or are supposed to conform to the ‘perfect,’ that is to say normal human type.” Parmelee goes on to argue that as a result of this aesthetic subjectivity, while nudism celebrated the beauty of the natural body, “external racial traits, such as color and shape of the features, are usually regarded as ugly and sometimes as grotesque by other races.” While a classicist upholding the physical ideals of white beauty and the supremacy of Western civilization, he also believed that racial prejudice, by keeping people segregated, stood in the way of a nudist social revolution, which was unfortunate because “the racial traits which may at first seem offensive and ugly will soon be ignored under gymnosophic usage.” For nudist egalitarianism to work, Parmelee concluded “it is of great importance…that race prejudice disappear entirely, or be reduced to the lowest possible minimum.” This, of course, was the catch: nudism could undo centuries of racism by exposing the fallacy that there was only one type of beautiful body—the white body. The problem was that centuries of racism fostered deeply held prejudices, prevented people with racially different bodies from growing “accustomed to seeing each other nude as well as clothed,” and reinforced the white body as a universal standard of natural beauty.

No wonder Parmelee made a point of saying that “race prejudice is, in fact, a serious problem for gymnosophy.”

American nudists in the first half of the twentieth century generally celebrated white bodies as more natural and beautiful than bodies of color, a view inconsistent with their romanticism of global indigenous bodies’ nakedness, health, and proximity to “uncivilized” nature.

Conflicting racial attitudes produced tensions in American nudist camps between members who accepted racial integration as a central tenet of nudism’s progressivism and those who did not, sometimes because they held racist views and sometimes because they thought racial integration to be politically imprudent. These positions, of course, were not mutually exclusive. The International Nudist Conference neither explicitly banned people of color, nor did its mission statement include them, asserting that membership was open to all ages and both sexes, and made no “tests of politics, religion, or opinion, provided that these are so held as not to obscure the purposes of the League.”

The first decade and a half of the nudist movement made the debate abstract as there were few nonwhite nudists, but this would change as soon as World War II ended and African American nudists would organize and challenge the racial segregation in the camps.

The call for integration was sparked in 1944 when E.J. Samuels, an African American nudist from Los Angeles, was invited by Sunshine and Health to write a series of columns on the politics and experiences of black nudism. Citing examples of pleasant visits with his wife to otherwise all-white nudist camps, Samuels wrote of experiencing racial equality among his white nudist brethren while also hoping to form his own integrated nudist camp that would feature a substantially more racially diverse membership. The American Sunbathing Association responded by refusing to admit African American members and instead encouraged black nudists to found their own magazines and camps. Samuels swiftly countered with the argument that segregated national nudist organizations were, if nothing else, economically unfeasible: “Less than 2 percent of the entire white population are nudists. And the Negroes, by themselves, could only support about seven or eight camps in the nation. As to a Negro nudist magazine—it would be out.” Samuels went on to suggest that “all nudists belong to the same national organization. Let the local clubs or groups be free to exercise their prerogatives in the matter of members. All support one magazine. In union there is strength.” While reminding Sunshine and Health’s readers that black soldiers had just fought in Europe to preserve democracy while Southern blacks were struggling to regain voting rights, Samuels envisioned a racially integrated free and natural lifestyle, asking, “Why not have brown, white, and black bodies drinking in the healthful benefits of our gorgeous sun?”

The American Sunbathing Association continued to oppose integrating the organization and went on the defensive arguing that it was black nudists who desired segregation. In a self-congratulatory tone, an editorial in Sunshine and Health explained that “throughout the interest recently manifested in the organization of negro nudist groups, the American Sunbathing Association has maintained a thoroughly sympathetic and cooperative attitude and shall gladly continue to do so. We believe that the best interests of nudism and the best interests of the negro groups both lie along the line of cultivating the negro groups until such time as they are sufficiently strong and numerous for them to have their own national association and possibly their own magazine. Until such time, we are with them and for them one hundred percent.”

Some members of the ASA backed the organization’s position, arguing that “mixing races in nudist camps at this time might seriously hurt or complicate the cause of nudism” while others, many of whom were ex-GIs, stridently challenged it, explaining that “the white man’s denial of equality to his black brother and the white man’s reluctance to practice the principles of brotherhood are fascist tendencies.” However loud the criticism, the ASA did not change its position until the early 1960s, when it incorporated the assertion that “no test of religion, race, creed, or politics may be made in judging the fitness of any applicant for membership” into its official policy. The damage, however, was done, and a 1964 scholarly study from Yale took note of how few bodies of color were to be found at American nudist camps. There were some, but not many. Moreover, the ASA club directory continued to list “black only” groups.

Excerpted from Free and Natural: Nudity and the American Cult of the Body by Sarah Schrank. Copyright © 2019 by University of Pennsylvania Press. Reprinted by permission.