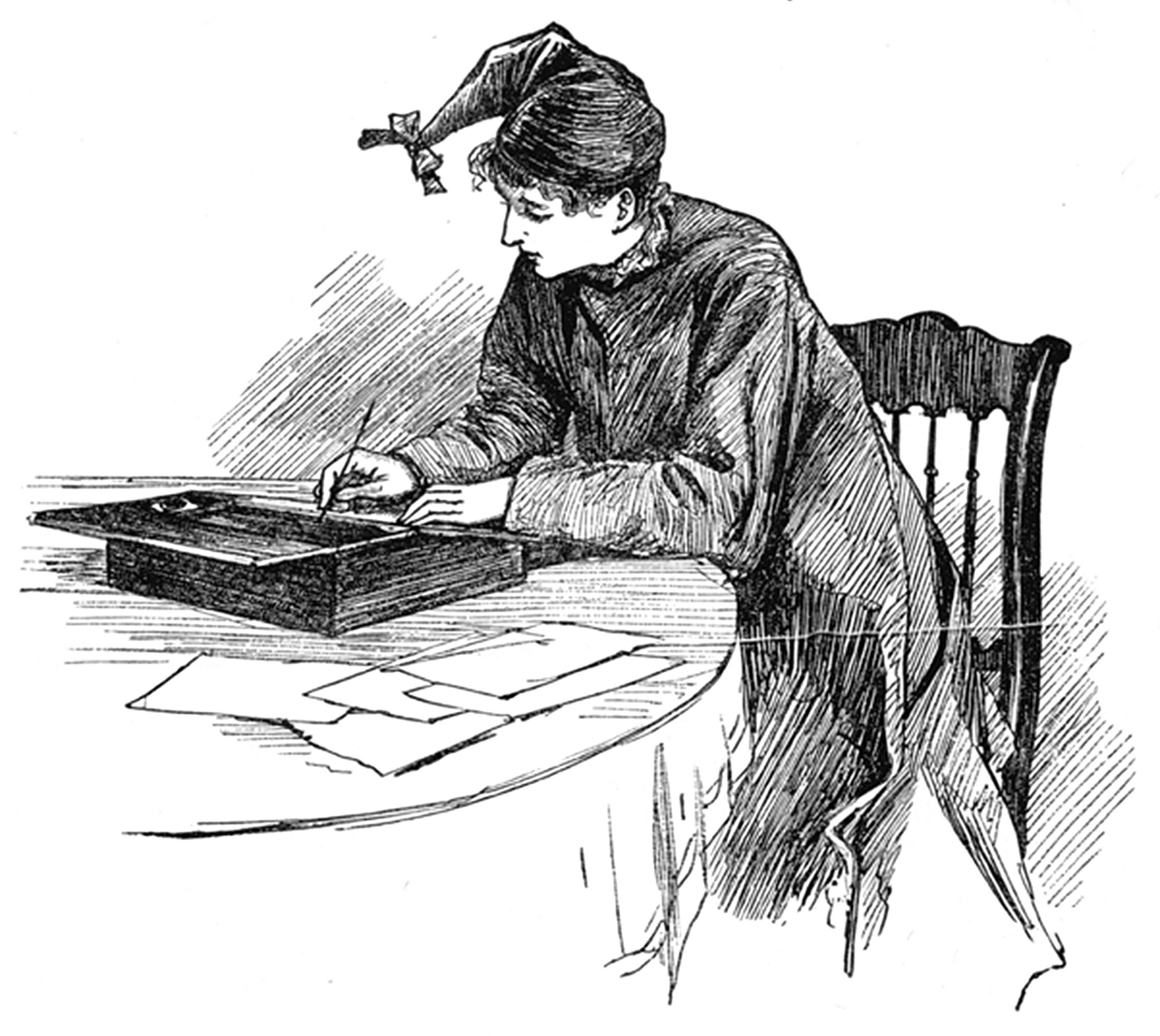

“Literary Lessons,” illustration from Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, by Frank T. Merrill, 1880.

Jo March turns 150 years old this fall. The rebellious tomboy—immortalized in the above drawing by Frank T. Merrill for the 1880 edition of Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, which was reprinted throughout the twentieth century—has inspired generations of girls to squirrel themselves away in their bedrooms or attics and warn family members not to disturb them while genius burns. Some of those girls grew up to be famous writers themselves, including Simone de Beauvoir, J.K. Rowling, and Barbara Kingsolver, to name only a few.

As Ursula K. LeGuin explained, Jo March was the original image of women writing:

This passion of work and this happiness which blessed her in doing it are fitted without fuss into a girl’s commonplace life at home. It may not seem much; but I don’t know where else I or many other girls like me, in my generation or my mother’s or my daughter’s, were to find this model, this validation.

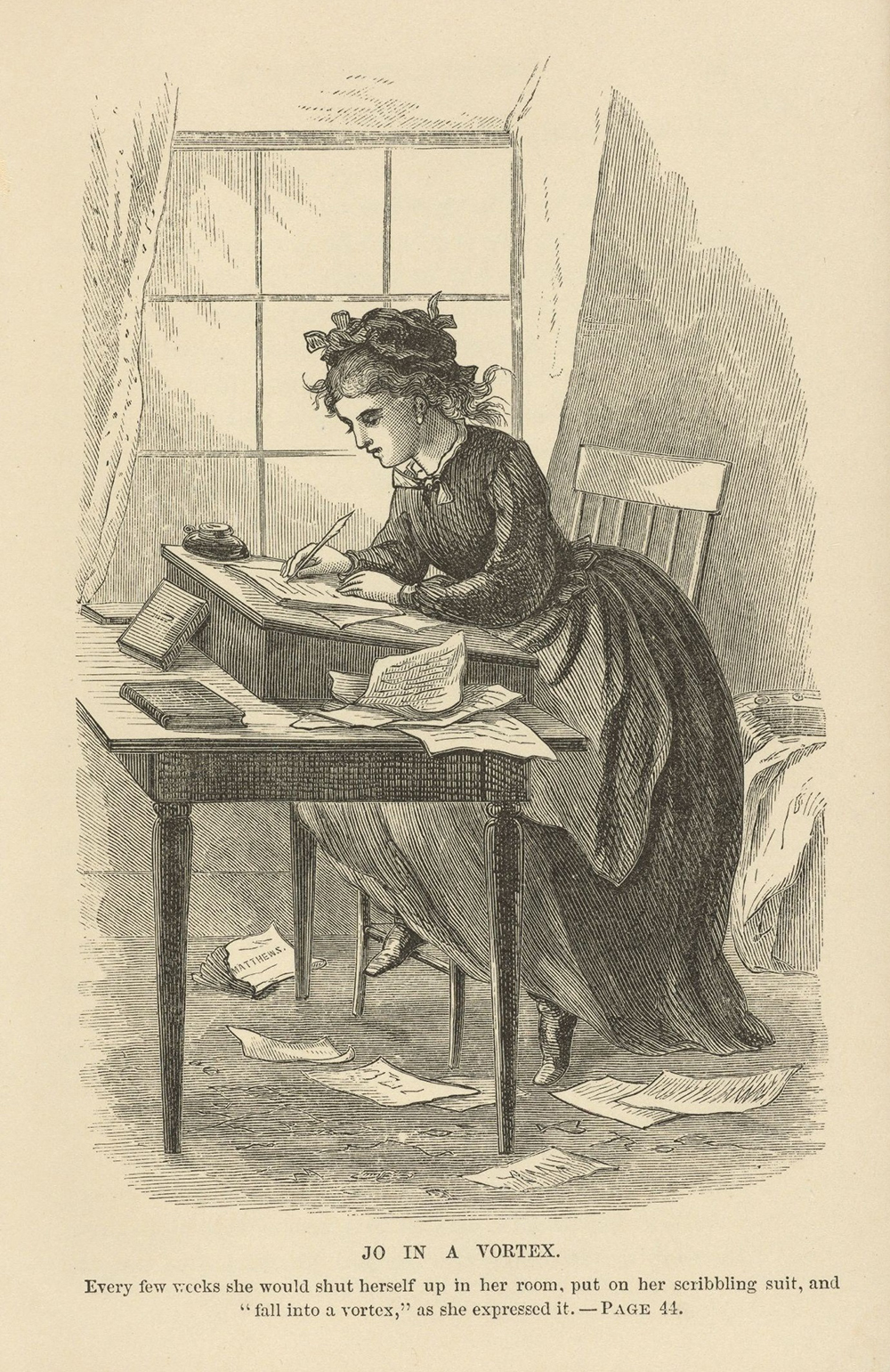

Our idea of Jo as a writer tends to stop there. She is remembered in her garret, leading a “blissful life, unconscious of want, care, or bad weather.” We may also recall that awful point in the novel where Amy burns her manuscript or the even more terrible scene where Jo nearly sets the chimney on fire, burning up her own stories. Most of us have preferred to dwell on the Jo full of promise and overflowing with stories that stream effortlessly from her pen.

Yet Jo’s career was more eventful and multifaceted than our memories tend to grant. Her struggles to find her place as an author mirror Alcott’s own, as well as those of many other women writers of the era.

Jo’s and Alcott’s families showered them with support and encouragement. When Louisa May Alcott was only eight years old, she wrote her first poem. She gave it to her mother, who responded, “You will grow up a Shakespeare!” Four years later, her father wrote in his journal that he believed one day Louisa’s “ready genius” would “make a way…in the world.” On her fourteenth birthday, he gave her a book into which he had copied her own original poetry, giving her a foretaste of the career he imagined for her.

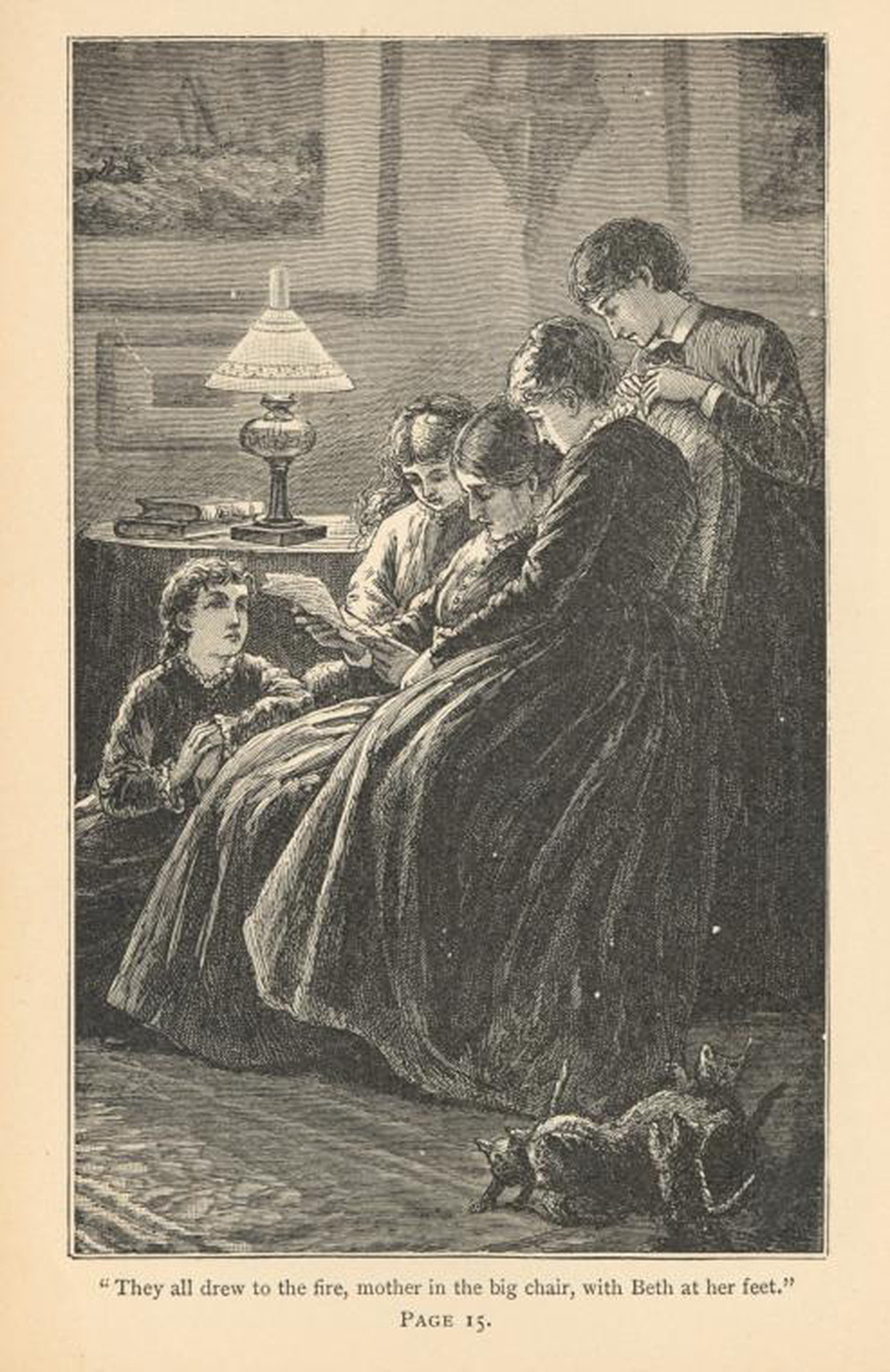

In Little Women, it is Beth who tells Jo, “You’re a regular Shakespeare!” When Jo reads aloud her first publication to her sisters, they unanimously proclaim their pride in her, a chorus soon joined by their mother, whom the girls affectionately call Marmee. When Jo announces that she wants to become a famous author, no one tells her it is a foolish dream or unbecoming of a young lady. But that is exactly the message that most girls heard in the mid-nineteenth century.

Women writ large were warned at every turn against picking up the pen. Critics stood, according to the novelist Elizabeth Stoddard, “ready to sneer at every woman who aspires to make use of the talents” God gave her. Henry James did exactly that to Alcott when she published her first novel, Moods, in 1864, four years before Little Women. In a lengthy, condescending review, James wrote, “The two most striking facts with regard to Moods are the author’s ignorance of human nature, and her self-confidence in spite of this ignorance.” The most remarkable thing about the review is the self-assurance of the critic, considering that James was ten years younger than Alcott but spoke to her as if she were the novice not only in literature but in life.

Male relatives could be even more discouraging. Fanny Fern, who was the highest-paid newspaper columnist of the time (at $100 per column in the New York Ledger), disclosed in her 1854 roman à clef Ruth Hall that her brother, a powerful editor, had discouraged her efforts to support herself as a writer after her husband’s death left her destitute, telling her she possessed no talent. Nathaniel Hawthorne, Alcott’s next-door neighbor, went so far as to tell his wife Sophia, a gifted writer, that he was glad she had “never prostituted [her]self to the public” by publishing her writings.

Such sentiments, however much the norm, appear nowhere in Little Women. Jo exhibits the usual anxieties about becoming a writer—Is she good enough? Can she make some money at it?—but none that are particularly gendered. Nonetheless, the trajectory of her career was very much informed by the impact of female writers on the literary marketplace, which led to a highly gendered split between highbrow and popular literature—the presumption that men write important, lasting books while women write ephemeral bestsellers—that remains with us today. Nearly all of the women writers of the nineteenth century who gained widespread fame—from Rebecca Harding Davis and Harriet Prescott Spofford to Constance Fenimore Woolson—are barely known today outside of academia.

This state of affairs can be traced to the 1850s, when Alcott was coming of age as a writer. The success of women’s books—three of the top best sellers of the era were Susan Warner’s Wide, Wide World (1850), Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), and Maria Cummins’ The Lamplighter (1854)—caused tremendous alarm among male writers and critics. In 1853 the United States Review called on “American authors [to] be men and heroes!…Do not leave literature in the hands of a few industrious females.” Hawthorne famously wrote to his publisher in 1855, “America is now wholly given over to a damned mob of scribbling women, and I should have no chance of success when the public taste is occupied by their trash.”

Yet such examples of female writers’ successes inspired a host of women to follow in their footsteps. Some made it, but many others failed. Their stories are told in a sad series published in Harper’s Magazine in 1867, the year before Little Women appeared, under the titles “A Weak-Minded Woman” and “Another Weak-Minded Woman.” These anonymous women speak of the deadening round of domestic labor they must perform and their yearning to rise above it by becoming authors. A response by the successful writer Elizabeth Stuart Phelps counseled the “legions” of women she imagined these two represented not to count on publication “to take away that persistent disquiet, or to hire an Irish girl.” But in the absence of virtually any other viable path to a decent income—let alone riches—for women, the lure of authorship was strong.

Jo was very much like these so-called weak-minded women: having grown up with a tremendous ambition to be famous, she looked to a literary career for an answer to her family’s financial troubles. Fortunately, unlike them, she finds some success. Early on she decides to take as her model the writer Mrs. S.L.A.N.G. Northbury, whose thrilling tales fill the cheap illustrated newspapers. The comically named writer was clearly modeled on the phenomenally successful E.D.E.N. Southworth, who wrote for the New York Ledger (also Fanny Fern’s paper). The paper reached about a million readers, and she earned about $10,000 a year from her melodramatic newspaper stories and novels with titles such as The Missing Bride and Mystery of Raven Rocks, which were full of feisty heroines battling evil men.

Alcott had gone down this path, too, despite her conflicted feelings. After she won a $100 prize for a thrilling story, Alcott began to churn out more sensational pieces in secret for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, most published under the pseudonym A.M. Barnard. They gave her a steady and easy income, made necessary by her father’s impracticality. The $40 to $50 she earned per story allowed her to give up the other occupations she had tried, such as teaching and sewing, each of which could earn her only about $50 per year.

Jo also won a $100 prize for a story in Little Women, after which her father tells her, “You can do better than this, Jo. Aim at the highest, and never mind the money.” After her literary win, Jo decides to put all of her ambitions into writing a serious novel, which publishers tell her must be heavily revised. Her father advises her not to spoil her book and instead let it ripen, while Amy says she should do whatever the publisher wants in order to make it a popular book. Eventually Jo follows Amy’s advice, but she finds that she has pleased no one in the process. Reviews are mixed; discouraged and defeated, she turns her attention back to writing for money, putting her ambitions aside.

Such was the exact experience Alcott had with her first novel Moods, about a volatile girl’s precarious journey toward adulthood and an ill-fated marriage. It was Alcott’s discussion of unhappy marriages that drew the fire of some critics, including James, who didn’t believe a single woman could have an informed opinion on the topic. In Little Women, Alcott avoided bringing up the subject altogether.

When Jo goes to New York, she chooses to focus on writing for the illustrated papers, just like her creator, setting her sights on the Weekly Volcano. The editor, Mr. Dashwood, agrees to pay her $25 to $30 per story. Thus she begins scribbling stories about criminals and innocent victims, relying on police records and insane asylums for material and justifying her descent into sensationalism with the good use to which she will put the income. She begins sending home money to care for Beth, who had never fully recovered from her near-death bout of scarlet fever.

Meanwhile, her new friend Professor Bhaer, a poor professor from Germany who impresses Jo with his generosity and knowledge, urges her to take Shakespeare as a model, counseling her “to study simple, true, and lovely characters, wherever she found them.” Rather than mine her imagination, she should observe and write from life, he tells her. Eventually, when he denounces the Weekly Volcano, she promptly burns her stories and vows never to write them again. For feminist critics, this scene has represented the height of patriarchal belittlement. But for Alcott it was a portrait of the developing writer. The fire Jo makes does not signify the end of her career—it is only getting started.

Having given up on the market for sensationalism, Jo goes to the other extreme, trying her hand at writing pious stories, adopting as her models the Evangelical Christian authors of an earlier era: Mary Martha Sherwood, Hannah Moore, and Maria Edgeworth. No editor wants to publish her didactic sermons, so she tries writing for children, a field dominated by the Sunday school market. Again, she fails. She decides that she will wait to write again until she has lived a little and has something more “honest” to say.

That time comes after the death of her beloved sister Beth. It is Marmee who reminds her how much happiness her pen has given her. So Jo returns to her desk and begins to “overhaul her half-finished manuscripts.” Having taken her mother’s advice to write for her family rather than the world, she hits upon a form of sentimental realism that touches her readers’ hearts and brings publishers knocking on her door. “There is truth in it Jo—that’s the secret; humor and pathos make it alive, and you have found your style at last,” her father tells her, triumphantly pointing out that she “wrote with no thought of fame or money, and put your heart into it.”

This was the style in which Alcott had written her runaway early success, Hospital Sketches (1863), about her experiences as a nurse during the Civil War, as well as Little Women. Alcott had indeed found her style at last, one that made her a pioneer in the kind of writing that women in particular would become known for. As Susan Cheever has written, “Without intending to, Louisa May Alcott found a new way to write about the ordinary lives of women, and to tell stories that are usually heard in kitchens or bedrooms.”

Alcott had hoped to leave Jo there, allowing her to live happily as a “literary spinster.” But after part one was published, her young readers wrote her letters demanding to know who the girls married. They weren’t going to be satisfied with spinsterhood. When Jo marries Professor Bhaer and has two children, she chooses family over her career, but not forever. “I haven’t given up the hope that I may write a good book yet,” she says in the novel’s final pages. In the third book of the March family trilogy, Jo’s Boys (1886), she does exactly that and becomes a famous author, her career reflecting again Alcott’s own.

Jo came a long way from her early days in the garret. After a rocky start, she realized her potential, making Little Women not only a coming-of-age story of four New England sisters but also a female Künstlerroman, the story of a woman artist’s development. We are fortunate that Alcott created such a positive image of the “original” woman writer, considering the highly negative portrayals of “authoresses” that prevailed in the popular press and, alas, even in women’s own writings (see, for instance, Mary Wilkins Freeman’s “The Poetess” or Constance Fenimore Woolson’s “Miss Grief”). We can benefit not only from Alcott’s portrait of a girl scribbling away in the attic but also from her more complicated portrait of a young woman finding her way through the ups and downs of a gendered literary marketplace.