The Bullion Mine, Virginia City, Nevada, by Carleton Watkins, c. 1875. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Digital image courtesy the Getty’s Open Content Program.

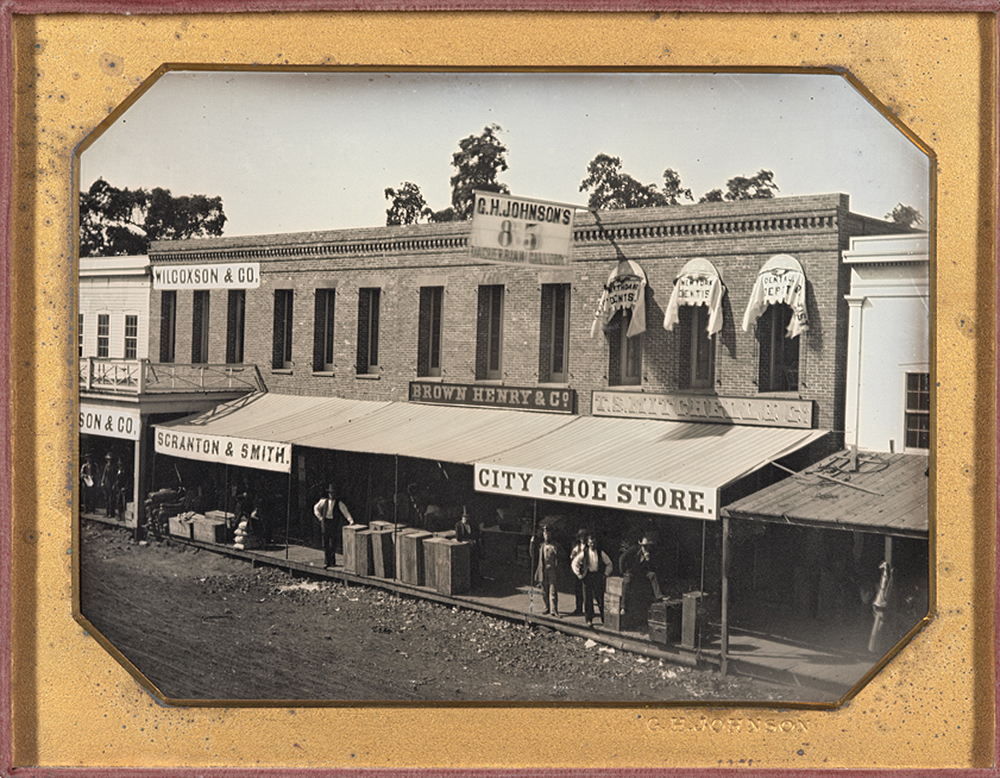

Born in New York State, George H. Johnson was one of the most prolific and important daguerreotypists to work in California. It is unclear where and when he learned the daguerreotype trade. An article in the Illustrated California News suggests the possibility of experience in Europe, noting that Johnson had “known this delicate art from its infancy, in the Old World as well as in the New.” He arrived in San Francisco in January 1849 from New York City, where he had been a daguerreotypist in at least 1847 and 1848. In July 1849 the opening of his first studio in Sacramento warranted a mention in the local newspaper: “Mr. Johnson, Front St. next door to our Office, is taking some admirable pictures. Mr. J has recently arrived from New York and is an artist of skill and taste.”

It is not surprising to find this early mention of Johnson in an article rather than an advertisement. Throughout his California career, Johnson maintained a cordial relationship with a number of newspapers. He understood how to promote his business through the press, regularly sending images to various publications in order to gain a positive mention or, better yet, an engraved reproduction of one of his views. In this way, Johnson made his name known to a wider audience than his actual plates could reach.

In Sacramento, Johnson probably exclusively produced portraits, including many of miners, into the spring of 1850. His studio setup was primitive, “on the ground floor literally and had canvas sides and a roof,” according to the Sacramento Transcript. By May 1850, he had moved to a more permanent location in the city, on J Street, and was ready to take likenesses “singly or in groups,” another newspaper noted. Notably, he was the only Sacramento-based daguerreotypist listed in the national registry of the first issue of the Daguerreian Journal in November 1850. A later advertisement claimed that his “establishment was the first permanently located one of the kind on the Pacific.”

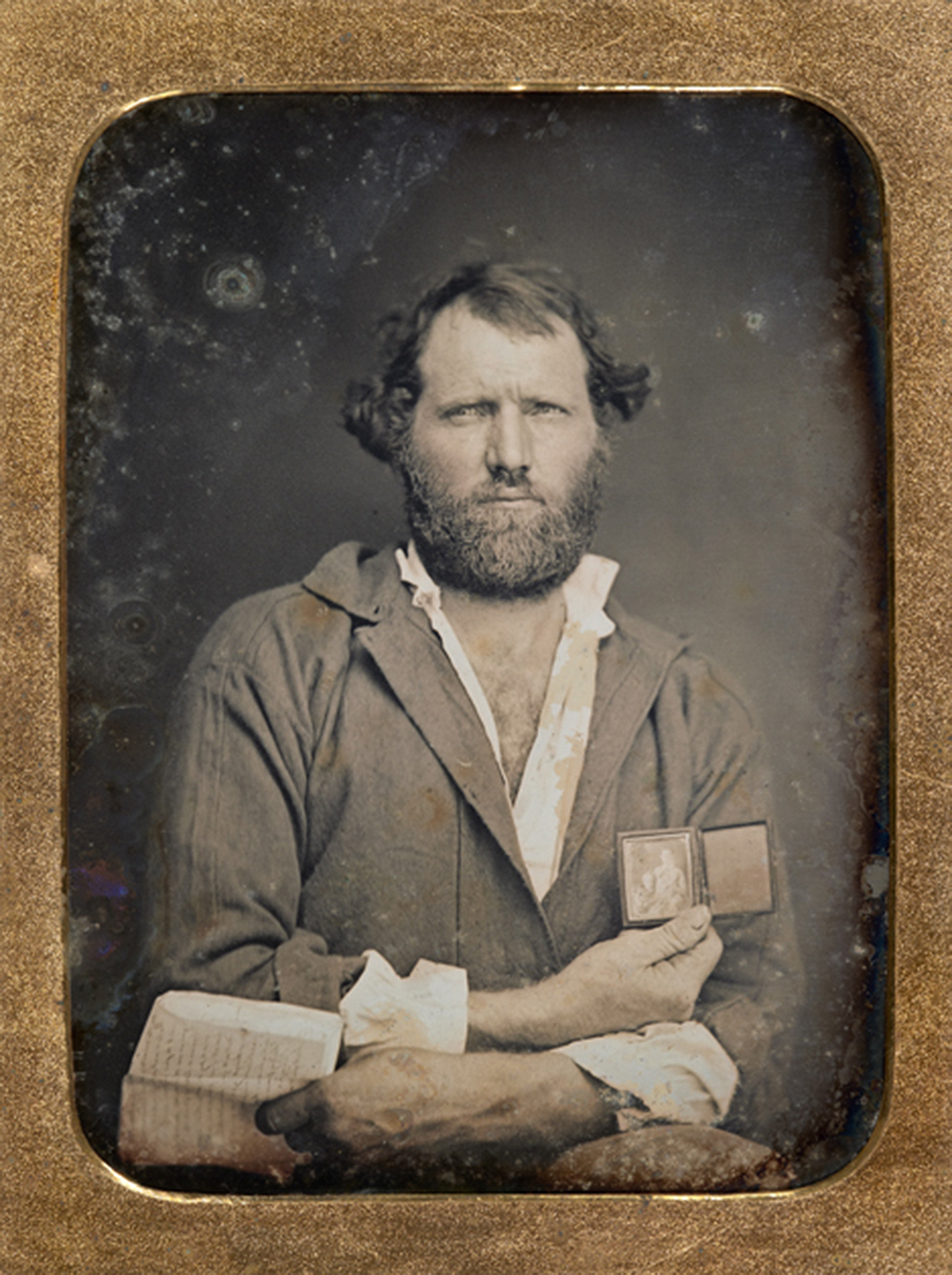

While Johnson is renowned for making views in the gold fields, it is not certain when this work began. It seems unlikely that he daguerreotyped outside prior to spring 1850 due to heavy winter rains. However, Johnson’s entry in the July 1850 city directory, as a “Daguerrean Artist, Facial and Landscape Gallery” indicates that he had undertaken outdoor views by this time. By July 1850, Johnson appears to have become a specialist in producing miner portraits, outfitting his studio with “a fine painting for a background, where miners desire to be represented at work.” The editors of the Transcript encouraged readers to obtain a daguerreotype “to convey to their friends and relatives at home something of an idea of their appearance in this country, where razors have become obsolete, and digging gold works such a powerful change in every man.” Johnson, it would seem, had a special ability for showing the essence of the miner, so that each man could see the true nature of “themselves reflected.” With a “living-like impress,” these portraits were acceptable surrogates to be sent home in lieu of wayward miners. The editors continued, “We recommend such of our friends as promised to return to their early homes this season, and who have failed in their promise, to drop in at Johnson’s to get a picture, and it will obviate the necessity for an early return.”

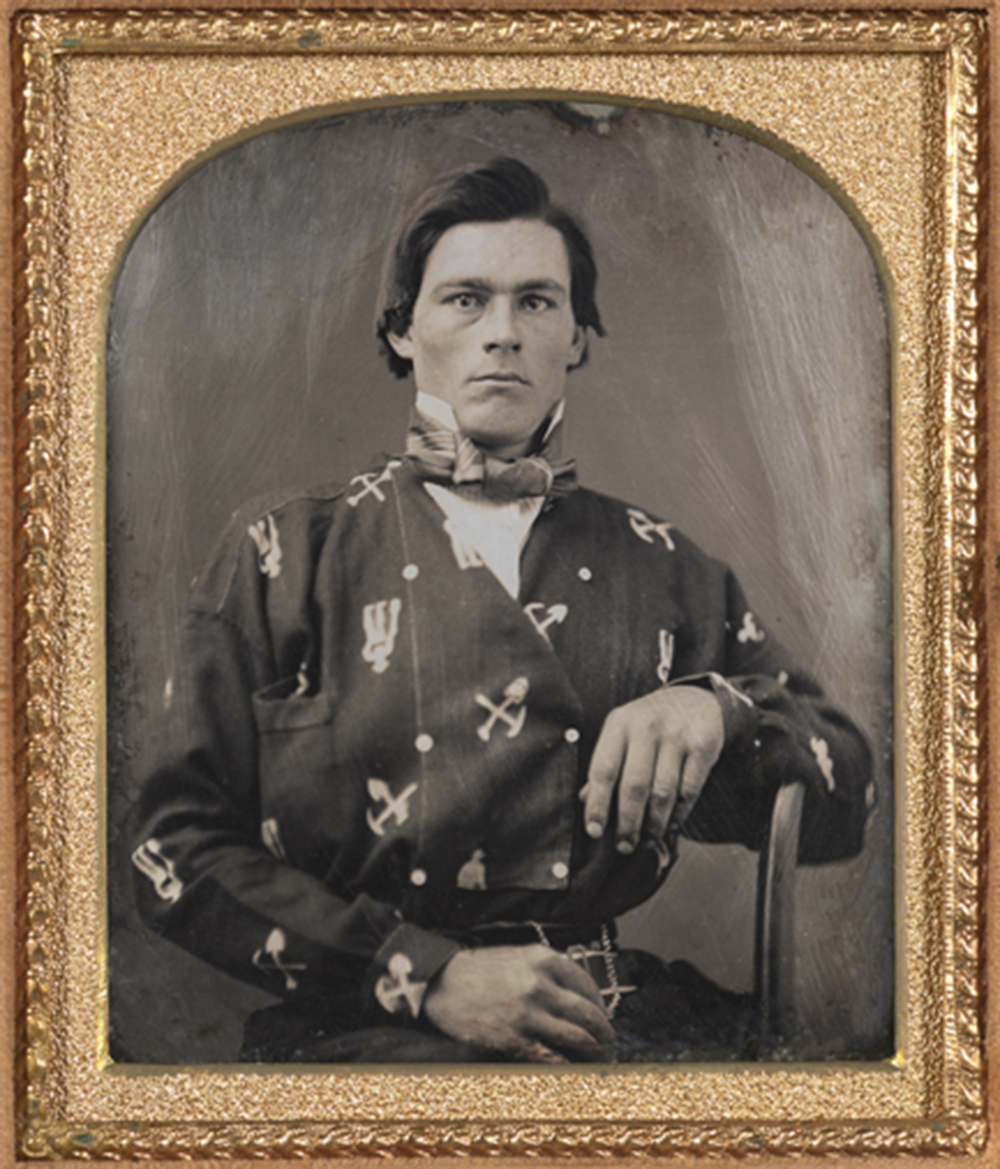

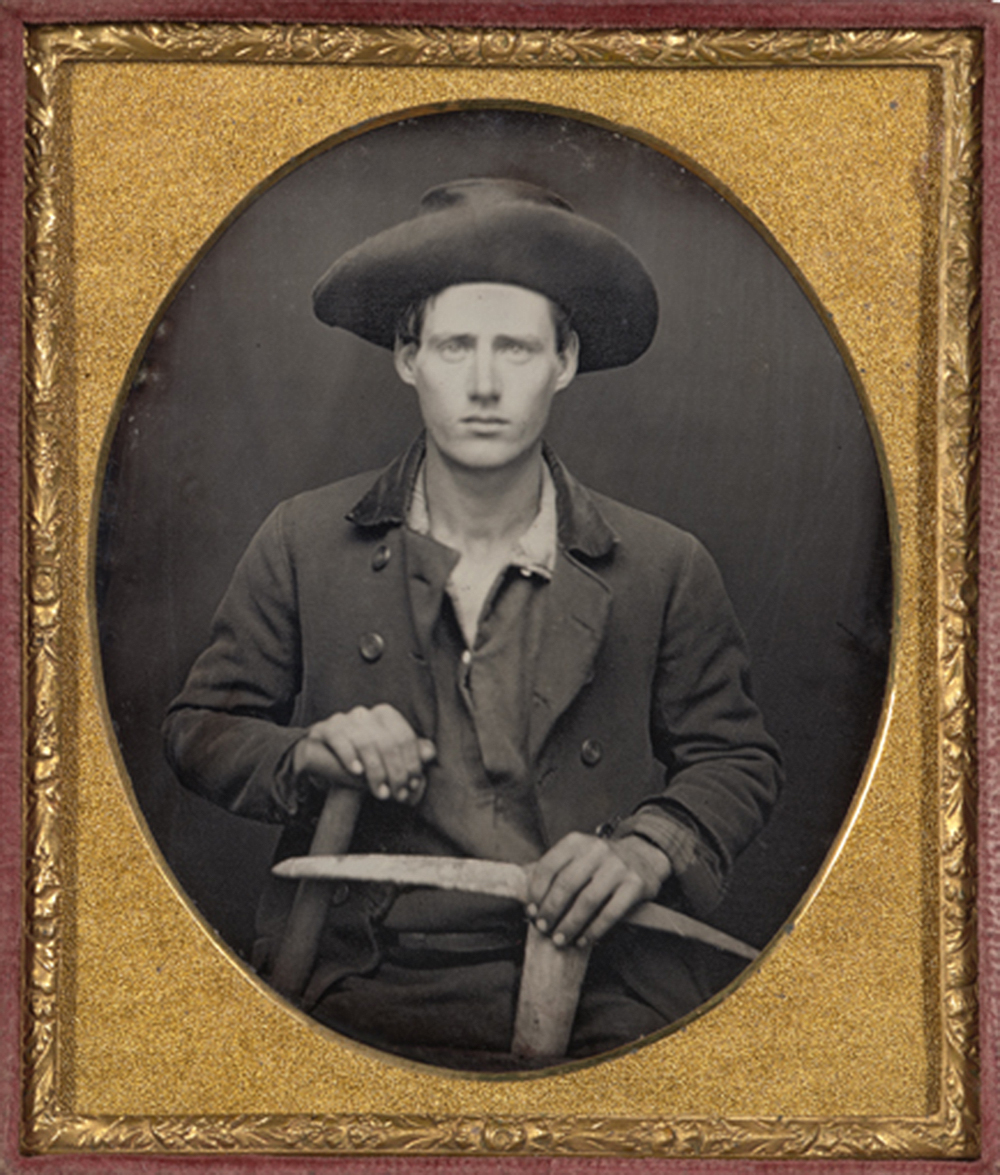

Upon arrival in California, freshly outfitted miners were especially eager to have their likenesses taken. In most miner portraits, great emphasis was placed on “looking the part”—wearing the clothing and holding the tools associated with gold mining. The California studios reported that on days just before a ship was to return east, “the gallery would be filled with miners in rough suits carrying their mining tools and a pair of pistols in the belt,” and that the studio would make “several sittings before [a sitter] left the chair and usually sold them all.” It seemed remarkable that

Californians were so anxious that their friends in civilized countries should see just how they looked in their mining dress, with their terrible revolver, the handle protruding menacingly from the holster, somehow, twisted in front, when sitting for a daguerreotype to send to the States! They were proud of their curling mustaches and flowing beards.

Daguerreotypists like George Johnson encouraged this desire to be photographed in mining attire. Capitalizing on a prime opportunity, Johnson advertised that all interested in “sending their miniatures home, or of being ‘preserved’ in the recherché costume of this latitude to give him a call.”

To be daguerreotyped as a miner had larger social and cultural implications. From the beginning, the gold rush was considered an historic adventure of mythic proportions. As historian J.S. Holliday has noted, “1849 will ever be a memorable epoch in the history of our country. Neither the Crusades nor Alexander’s expedition to India (all things considered) can equal this emigration to California.” Miner portraits were made to confirm and commemorate participation in this once-in-a-lifetime experience. As these portraits were sent to loved ones left behind, even those who had not directly participated could establish a personal connection to this great event. The personal separations caused by the gold rush were difficult. Because the journey to California involved months of arduous travel, miners were not only separated from, but for a time unreachable by, their loved ones. Once in California, a miner faced the realities of brutal labor, likely disappointment, and fear of the unknown. To fill the void of separation, a daguerreotype portrait preserved the appearance of a missing son, brother, or husband, unchanged through time and distance. Letters and daguerreotypes helped families back home reinforce emotional ties and participate vicariously in the miner’s distant experience.

Miner portraits were a part of the larger narrative that was the “gold rush myth.” For the first time in American history, it seemed possible through hard work and determination for a “common man and woman, the most ordinary individual, a person without even the money to get to California, the lowly peasant of centuries of European society” to rise to a higher class in society. The gold rush presented the possibility of a new democratic society based on initiative, luck, and quick wealth. The fact that most participants never struck it rich was irrelevant; the tantalizing chance that the incredible was possible perpetuated the myth.

Miners were typically daguerreotyped in work shirts, often tinted in the traditional mining color of red. A few men, interested in looking their best, wore nicer shirts with ties. Clothing with holes or patched knees were not the result of a dire financial circumstance but rather an indication of the time miners had spent in the field. Miners of 1849 were humorously described as having “ragged clothes covering lots of gold, and long hair and whiskers, springing from piles of dirt, in faces that perhaps lately adorned the walks of civilized life.” Regardless of prior societal standing, participants in the gold rush—assuming they were white males—were all considered equal in the field.

Most men proudly wore beards—sometimes quite unruly and long—indicating a dedication to work (they could not be bothered to shave). For some, the choice was predetermined; these men were too young to grow whiskers. The essential miner’s hat, also known as a wideawake, was meant to be worn straight on the head to protect from the heat and glare of the sun. In the comfort of the studio, however, miners often tilted their hats back at a rakish angle to reveal their entire face. Most miners wore their hats in their portraits; those that did not often set them on a nearby table. For those choosing not to wear a hat, their wild, uncontrolled hair became the focal point of the composition.

The most common tools pictured in miner portraits were the pan, the pickax, and the shovel. It could be challenging to hold multiple tools, but these portraits could appear effortlessly done. These tools stood as emblems for the idea of the “lone miner” with individual determinism and the willingness to work, the traits necessary to become a wealthy man. Of course, any suggestion of a romantic, easygoing life was greatly at odds with reality. Gold was easily gathered only in the earliest years of the rush, before most Americans arrived. More typically, mining was backbreaking work that barely covered the cost of necessities. Huge windfalls were few and far between. As a result, individual efforts inevitably gave way to organized, corporate mining operations. Nevertheless, the ideal of the lone, successful miner persisted well beyond his actual existence. Miners wearing pistols and large knives in daguerreotype portraits referenced the image of lawlessness in 1850s California. For many miners, part of the lure of the quest for gold was participation in the exciting adventure, including outfoxing fellow miners, thwarting cheats and robbers, and adapting to unpredictable weather conditions. Although danger was real, many used guns only for hunting and knives only for digging in crevices for particles of gold.

Some lucky miners were daguerreotyped with gold nuggets, gold dust, or gold jewelry. These objects were hand-gilded directly on the daguerreotype surface, giving an otherwise monochromatic plate an unexpected sparkle. Miners also proudly displayed stickpins, watch chains, and rings with gold. Bags of gold dust, instantly recognizable by all Californians, were balanced on studio pedestals or stuffed conspicuously in bulging shirt pockets. (This bag was sometimes referred to as “poke.”) One young miner was daguerreotyped with his arm protectively cradling a large chunk of gold-veined quartz. Upturned mining pans filled with gold directly connected the earliest gold mining technology with the hoped-for result. These gold-laden portraits signified the ultimate success, in terms that every viewer understood.

Excerpted from Golden Prospects: Daguerreotypes of the California Gold Rush, by Jane L. Aspinwall, with contributions by Keith F. Davis, published by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2019 by the Hall Family Foundation, Kansas City, Missouri, and the Trustees of the Nelson Gallery Foundation, Kansas City, Missouri. Reprinted by permission. The exhibition Golden Prospects: California Gold Rush Daguerreotypes is open to the public at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri, until January 26, 2020. It will be at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, from April 4 to July 12, 2020, and at the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven, Connecticut, from August 28 to November 29, 2020.