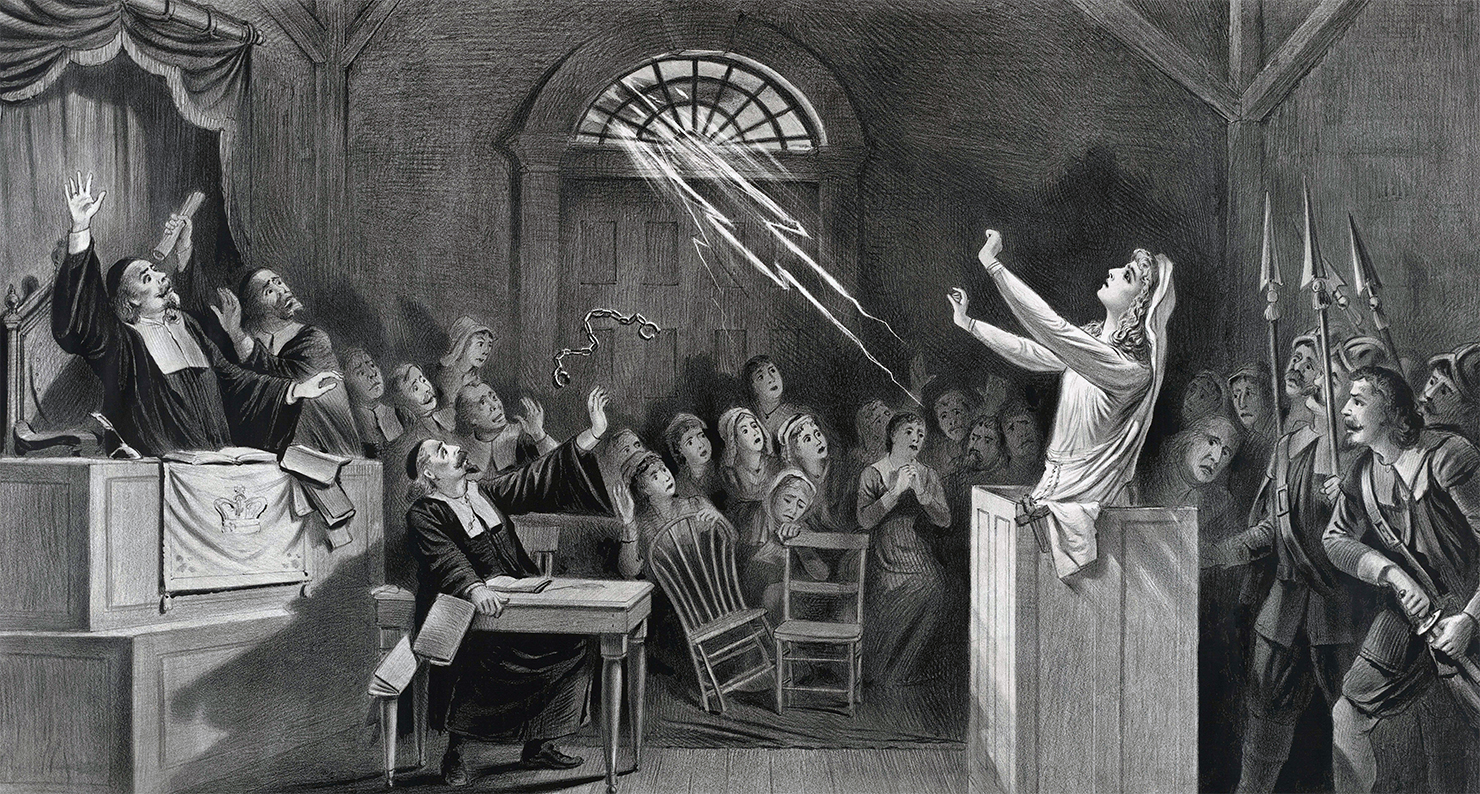

The Witch No. 1, by Joseph E. Baker, 1892. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

In 1597 a grim invoice made its way to the family of Cathin Joyeuse, recently deceased. Known to her fellow villagers of Toul, France, as the Mayoress Etienne, the bill’s itemized contents were sober and matter-of-fact, a collection of figures and sums belying the startling ordeal the Mayoress had faced during her last month on earth: ten francs for the attorney, twenty for “him who conducted the trial,” one franc owed to the “woman who shaved her,” four required for “inspecting the court record,” and twenty francs due to the torturer for services rendered. Like countless others accused of witchcraft in Renaissance Europe, Joyeuse had fallen prey to a vile, codified process of imprisonment, torture, coerced confession, and execution. In their grief, her family was now forced to foot the bill.

“Witch hunting,” wrote the historian Rossell Hope Robbins, “was self-sustaining and became a major trade, employing many people, all battening on the savings of the victims.” The costs of a witch trial were usually paid for by the estate of the accused or their family. Far from the conventional image of a penniless hag, a significant proportion of accused witches, especially in Germany, were wealthy and male. Their property was seized to pay the clergymen, judges, physicians, torturers, guards, scribes, and laborers who raked in increasingly large sums of money, as well as other reliable assets. With a single member accused, a moderately wealthy family could be ruined permanently. Father Cornelius Loos, the first German critic of the witch hunts, wrote in 1592:

Wretched creatures are compelled by the severity of the torture to confess things they have never done, and so by cruel butchery innocent lives are taken; and, by a new alchemy, gold and silver are coined from human blood.

After a bill had been paid, the property that remained was susceptible to seizure by kings, bishops, local noblemen, autonomous towns, or the Inquisition itself. In Elizabethan England, where witchcraft carried a life sentence, the possessions of the accused became property of the Crown. In seventeenth-century Salem, Massachusetts, the legislation demanded that those acquitted remain in jail until they had paid off the cost of their unlawful imprisonment. In one famous instance, Tituba, a key witness exonerated in 1693 during the Salem witch trials, lacked the money to pay for her thirteen-month incarceration. She remained in prison—with ever-mounting debt—until an unknown person finally paid for her purchase as a slave.

A sampling of witch-trial bills reveals unique and often peculiar regional practices. Shackles for a man in Salem cost five shillings, while handcuffs and lighter leg shackles for a woman ran seven shillings, six pence. Those accused in Offenberg, Germany, were charged as much as thirty-two florins for the “entertainment and banquet of the judges, priests, and advocate” after every court session. One hapless Frenchman in 1659 was ordered to pay the cost of searching his house for “witch powders.” In Scotland, reflecting the country’s preferred method of burning, two Aberdeen witches in 1596 were charged ninety shillings, eight pence for “twenty loads of peat,” “a boll [six bushels] of coal,” and “four tar barrels,” a bill equivalent to about $1,800 today. A more unmistakable example of the pain-for-pay ethos of Europe’s witch hunts is the “Tariff for Torture,” a document approved in 1757 by the Archbishopric of Cologne to enact a standardized “price list” for such gruesome services as “terrorizing by showing the instruments of torture” (one reichsthaler, the currency of the Holy Roman Empire), “putting in the pillory, branding, and whipping” (two reichsthaler), “cutting out the tongue entirely” (five reichsthaler), and “breaking alive on the wheel” (four reichsthaler), around the cost of one volume of Bach sheet music at the time.

“This movement was promoted by many in office, who looked for wealth in the ashes of the victims,” wrote Johann Linden, a canon of Treves Cathedral, whose History of Treves (1590) is an important chronicle of the big-business aspect of witch hunts:

And so, from court to court throughout the towns and villages of all the diocese scurried special accusers, inquisitors, notaries, jurors, judges, constables, dragging to trial and torture human beings of both sexes and burning them in great numbers…So far, at length, did the madness of the furious populace and of the courts go in this thirst for blood and booty that there was scarcely anybody who was not smirched by suspicion of this crime. Meanwhile notaries, copyists, and innkeepers grew rich. The executioner rode a blooded horse, like a noble of the court, and went clad in gold and silver; his wife vied with noble dames in the richness of her array.

Linden’s account captures the severity of Europe’s most intolerable period of witch hunts, which occurred from about 1580 to 1630. During this time, outbreaks and panics swept through villages and surrounding regions as confessions, under stress of pain, quickly led to the naming of other supposed accomplices. Though witch trials would continue intermittently throughout the first half of the eighteenth century, the most intense period of outbreaks gradually came to a close in many places with the disappearance of seizable property and the fading of profits. After the Holy Roman Emperor forbade the confiscation of property in 1630, witchcraft persecutions declined noticeably in some places. Bamberg, Germany, which had seen an average of a hundred executions a year from 1626 to 1629, burned that year only twenty-four; none were executed the year after. The city of Cologne, which had from the outset prohibited the seizing of property, experienced the fewest executions of any region of the Empire. Though the curbing of profits was not the sole reason for the halting of witch trials in every region, the desire to make a killing—as common then as it is today—suggests that it must have played some part in curtailing the practice. Linden, who had seen his city transformed into a circus of vested interests, describes how regulations were devised, the witch hunting industry wavered, then collapsed: “At last, though the flames were still unsated, the people grew impoverished, rules were made and enforced restricting the costs of examinations and the profits of the inquisitors, and suddenly, as when in war funds fail, the zeal of the persecutors died out.”