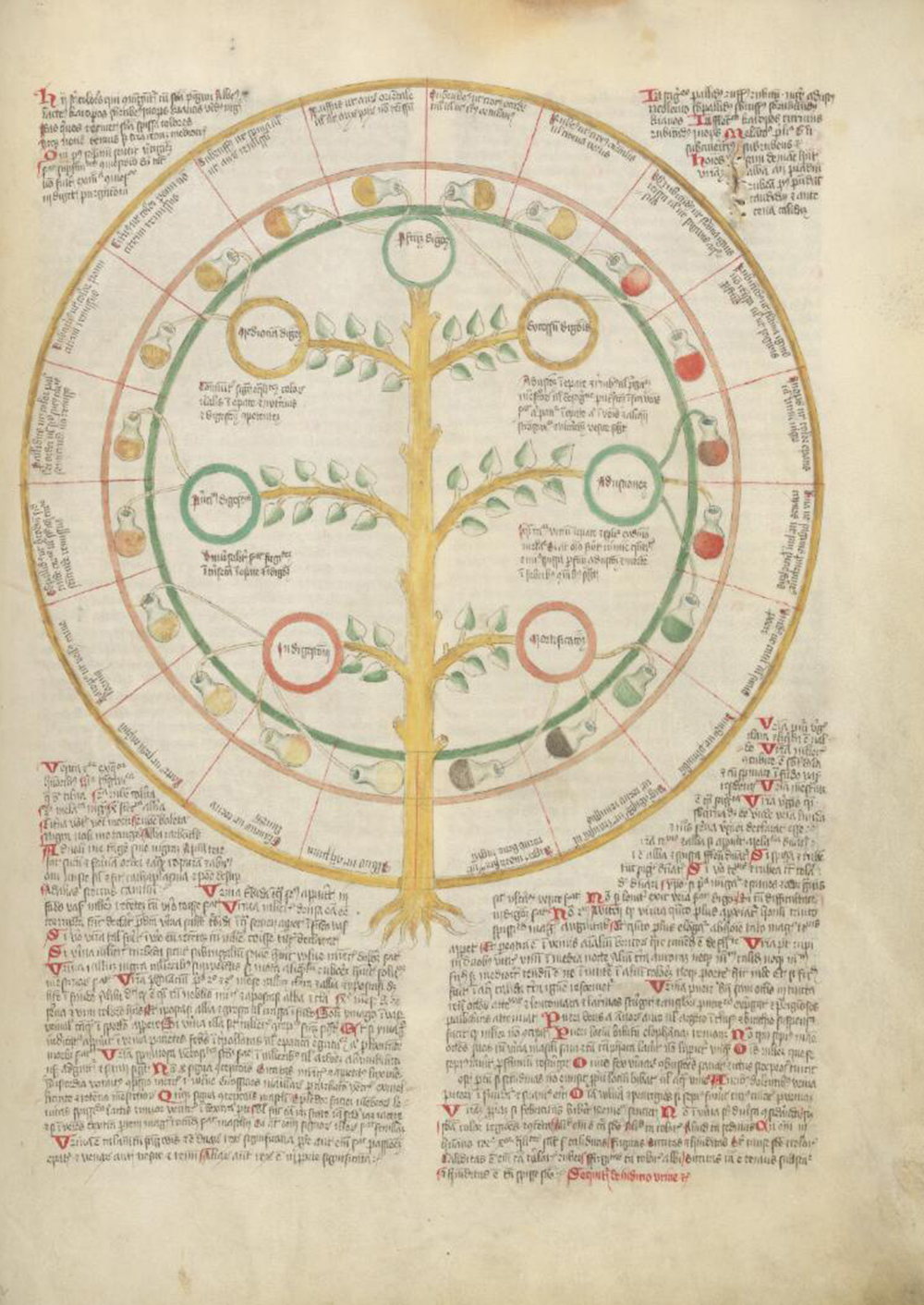

Urine wheel from Epiphanie medicorum by Ulrich Pinder, 1506. Folger Shakespeare Library.

In January 1475 a notary in Paris named Jean de Roye recorded that an archer had been found guilty of larceny. After being detained in the city’s prison, the man had been sentenced to hang at a large gibbet erected outside the capital’s walls, but on the day of his proposed punishment a petition was submitted to King Louis XI by a group of physicians and surgeons of the city. These professionals, Jean testified, believed that the body of the condemned was of some greater use. Invoking various common conditions—bladder stones, burning colic, and other painful internal maladies—the practitioners suggested it would be of great help for them in their diagnoses to see the very sites where these diseases were formed inside the human body, and that the best way of doing this, they claimed, was to cut open a living man. The petition was successful, and Jean goes on to record the opening of the man’s stomach, the inspection of his insides by the doctors, and, amazingly, that afterward his entrails were happily returned back into his belly before being sewn up again. Given the finest recuperative care, at the king’s expense no less, Jean writes that the archer made a full recovery within a fortnight, had his sentence of death pardoned, and was compensated handsomely for his troubles.

Much of this account seems bizarre to a modern reader: the royal petition by an interrogative band of physicians and surgeons, the archer’s speedy and seemingly untroubled recuperation from a stomach trauma that should surely have killed him, and, especially, his gruesome public vivisection. Such violent invasion of the body was certainly not the norm in Jean’s Paris. Unlike in Italy, where the physician Mondino da Luizzi had begun to make examinations of the body beneath the skin as early as 1315, in France religious and social restrictions still tightly controlled anatomies, so much so that it was not until the 1500s that observational dissections were regularly undertaken by Paris’ medical faculty. Perhaps, though, turning to this historical context to understand Jean’s strange story is only half the answer. Tales of the medieval body often had all sorts of meanings and metaphors at work under the surface. Could the archer opened at the stomach be a way of expressing something else, a broader French fascination with the body’s interior?

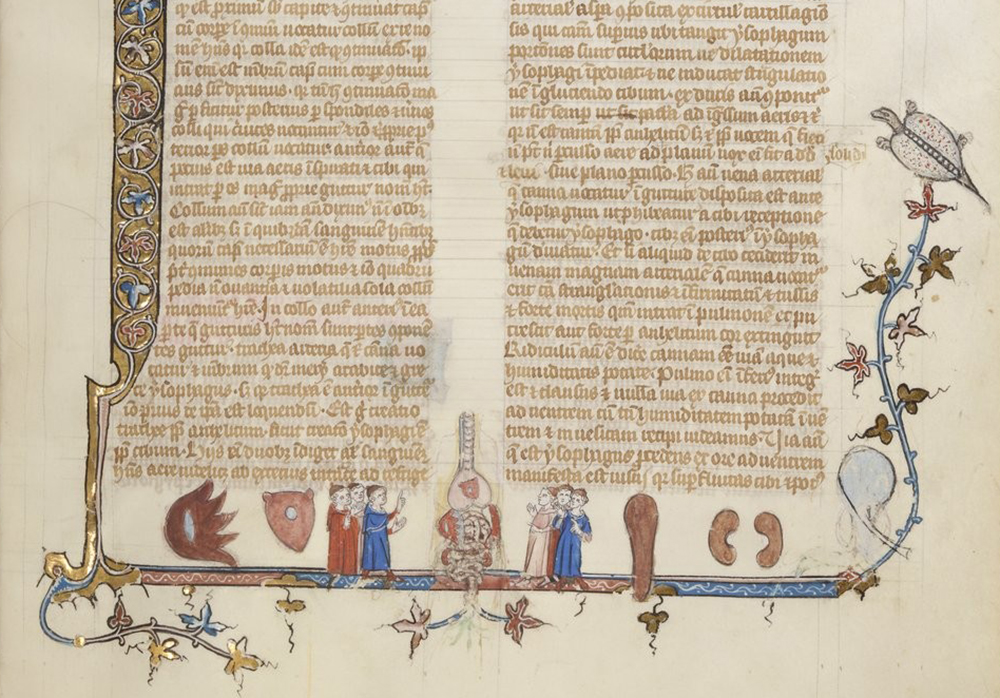

Today, technology has afforded us a real familiarity with our deepest innards in ways that premodern peoples would never have thought achievable. For most medieval men and women, the sight of one’s own entrails was the clearest possible sign that something had gone very wrong indeed and that death was imminent. Such fears, however, did not stop them from imagining what the interior of the body looked like. This certainly seems to be what is happening in a page from a fourteenth-century philosophical manuscript, also made in medieval Paris. Pretty typically for a relatively large and luxurious edition of a popular text—a commentary on Aristotle’s classic zoological treatise De animalibus (On Animals)—the parchment pages are thoroughly embellished with pen flourishes, illuminated initials, and even occasional marginal scenes, framed with floral motifs and inhabited by the text’s eponymous creatures feeding, fighting, and rutting. But on one folio, beneath the introduction to a chapter on the internal parts of living creatures, sits an enlarged gathering of internal organs arranged as if within a living human form. We are able to follow the long trachea downward toward the lungs and intestines, atop of which sit the liver, heart, stomach, bladder, and kidneys, while at the base of the entire system a tubular colon and anus morph seamlessly into twin branches of floral decoration. There is a real sense of revelation here, in which, like Jean’s archer, the skin has disappeared, allowing us to look directly at what lies beneath. The body is even flanked by a crowd of six physicians, deliberately identifiable by their doctoral gowns and bonnets, all staring up at the gigantic innards with frantic and awed gesticulations. The scene seems to show what the poet Francesco Petrarca—that godfather of the term medieval—once described as physicians’ “obsessive seeing,” always straining “to see that which lies within, the viscera and tissues.”

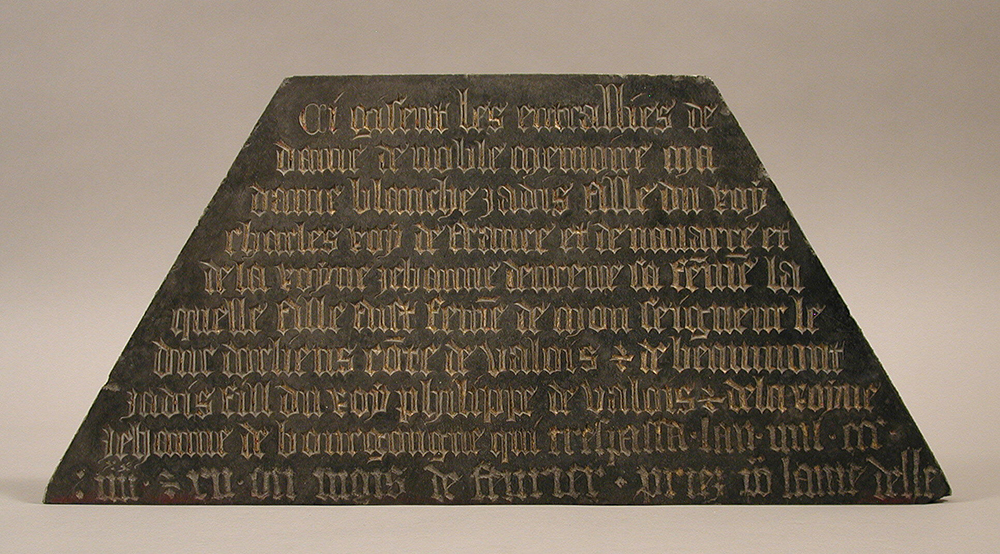

Contemporary events just outside Paris show just how obsessive this interest in innards could become. Take the medieval abbey of Maubuisson, just a few hours’ ride north of the capital. By the thirteenth century the area had come some way from the bandit hideaway which had earned it a name derived from buisson maudit, literally “bad bush.” The queen of France, Blanche of Castile, and her son King Louis IX had built a substantial royal complex there, complete with outbuildings, nuns’ quarters, and a large church to serve as a necropolis for their Capetian dynasty. Yet unlike the tombs of the English royalty at Westminster or the caliphs’ memorials in Cairo, this was not a space for the burial of French regal bodies in their entirety. Well aware that prayer at the site of the corpse could act as a conduit to end purgatorial suffering, the Capetians alighted on the idea of splitting their bodies in two in order to double their spiritual potential. Alphonse of Poitiers, King Louis’ brother, died in 1271 en route to France while returning from the Crusades, but had strictly stipulated that in such an event his entrails should be separated from his body and sent to Maubuisson for individual burial. Robert II of Artois, another prominent royal nobleman, followed suit, asking for his innards to be removed and interred in the foundation’s church, placed there on his death in 1302. Nearly thirty years later, Blanche’s great-great-grandson, and by then king of France, Charles IV, earned specific permission from the pope to have his body split into easily venerated pieces, his entrails sent to Maubuisson for burial. And fifty years after that, Charles’ wife and longtime widow, Jeanne d’Évreux, requested identical treatment to that of her husband on her death in 1371, as did one of Charles’ successors as king, Charles V, in 1380. Over the course of a century Maubuisson had become a dynastic memorial built on coils and coils of intestine.

The interred entrails of these French royals were given a leading role in their tombs at the abbey. Shortly before her death Jeanne d’Évreux commissioned the famed Flemish sculptor Jean de Liège to create a double tomb for the entrails of herself and her husband, King Charles, the upper sections of which still survive intact. They show two small marble effigies of the couple, around half life-size, both crowned and dressed in delicately sculpted royal robes, perfectly normal were it not for the small leather bags they each clutch to their chest, the soft curves of the pouches betraying neat shapes of intestine spiraled within. Carved in unsettling detail, they appear winding and twisted as if alive inside a sculpted stomach, curled up like links of miniature sausages. Charles V seems to have liked them so much that he commissioned Jean de Liège to make him an entrail tomb as well, yet another bundle of French guts set in stone at Maubuisson.

These burials were particularly cherished by the foundation’s nuns, who saw the remains as a marker of their abbey’s continuing importance to the crown. They prayed beside them in their church, wishing for the safe purgatorial repose of their queens, princes, and kings beyond the grave. And, as time went by, the royal stomachs occasionally offered back heavenly responses of their own. Abbey records from May 1652 show major renovations to Maubuisson’s church, during which a wall was breached by builders to reveal unexpectedly an unmarked, lead-lined box. Upon opening, it was found to contain Robert II of Artois’ three-hundred-year-old viscera. Witnesses described the innards as totally undecayed, “fresh, vermilion, and full-bloodied,” despite not appearing to have been specially preserved or embalmed. To mark the occasion they were displayed fully exposed for ten weeks, all the while never dulling in color and exuding a soft, sweet perfume throughout the church, miraculous entrails gutted from the abbey’s very walls.

One aspect of the body united all people, female and male alike: eventually, everyone needs to urinate. Within the logic of medieval humoral medicine, however, everything that was expelled from the body—sweat, vomit, saliva, feces—could be pored over for its quality and quantity by a knowledgeable healer for signs of underlying internal imbalance, and urine was no exception.

Texts from as early as the seventh century offered detailed guidance for physicians in uroscopic readings. We agree today that urine color can be an indicator of levels of hydration within the body, as well as various other measures of health, but this earlier medicine took urological divining to extremes. So focused were some physicians on reading urine that the round-bottomed flasks in which patients’ samples were presented to them quickly became a prominent part of their visual culture. Much like a modern white coat, a person in a medieval manuscript depicted peering at such a flask instantly identified themselves as a physician, although this was not necessarily a reifying gesture of respect. In the fifteenth-century stained-glass windows of York Minster, monkeys rather than men inspect urine bottles, a bawdy pastiche of the active medical scene in the city. In theatrical plays, too, bungling doctors also offered light comic relief through the bladder. In the so-called Croxton Play of the Sacrament, a rare surviving piece of English religious theater, a character called Master Brownditch of Brabant—whose name already suggests a certain coprological obsession—is described in particularly urine-laden terms:

The most famous phesycyan

That ever sawe uryne!

He seeth as wele at noone as at nyght,

And sumtyme by a candelleyt

Can gyf a judgyment aryght

As he that hathe noon eyn.

The most famous physician

That ever saw urine!

He sees as well at noon as at night,

And sometimes by a candlelight

Can give a judgement just as well

As one that has no eyes at all.

Urine is both Brownditch’s badge of honor and his failing, the proud marker of his trade and the basis for a backhanded compliment that his urological pronouncements are no better than those of a blind man.

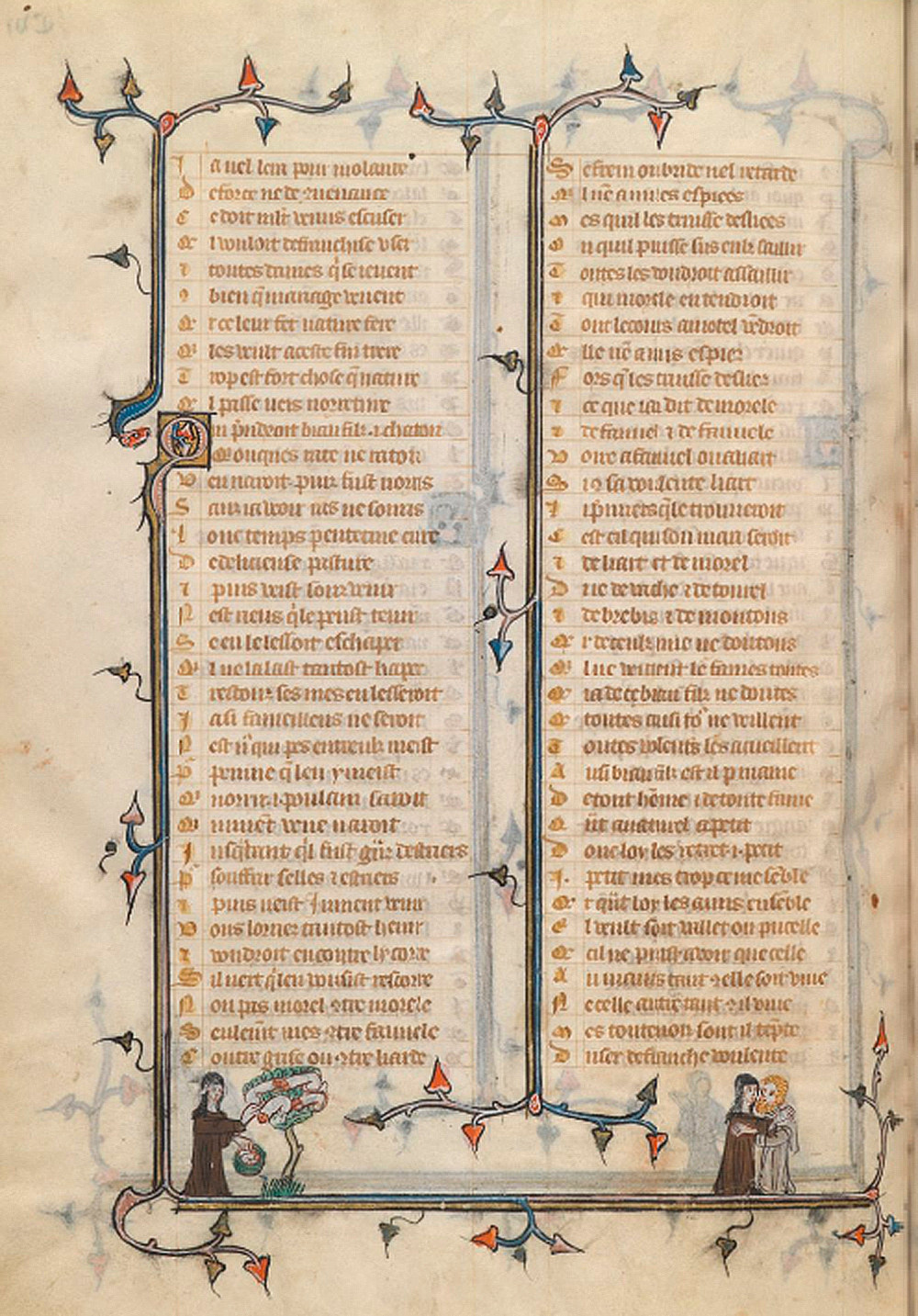

These colorful characters of the stage could be matched medically with equally colorful images. A beautiful tree complete with flowering roundels of piss sounds like something of a paradox, and yet this is how several medieval texts on uroscopy chose to frame their contents. A wheel of samples from a manuscript made around 1420 in Germany shows the detail that went into such prognoses, the culmination of many different theories on micturition. A circle of flasks are shown graded by color around a flourishing, seven-branched tree, a style of illustration that simultaneously echoes contemporary philosophical diagrams of virtues and vices, religious family trees mapping the genealogy of Christ, and, in a way, the penis trees which peppered the bas-de-page of novels like the Roman de la Rose. Each branch suggests a different broad diagnosis, ranging from indigestion to imminent death, while an outer layer offers abstract colorific descriptions picked up by the corresponding sample’s shade. Lowest on the scale we find albus (white), with the explanation that such urine is “as clear as well-water.” The circles then move through various grades of yellow—karopos (likened to camel’s hair or skin), subpallidus (like unreduced meat juice), rufus (like a fine gold or saffron)—before turning to different reds—rubicundus (like a low flame), inops (like an animal’s liver), and kyanos (like a darkened wine). Finally, after covering ever deeper greens—plumbeus (like the color of lead) and viridis (like a cabbage)—the wheel finishes with two ominous shades of black, one described as being like ink and the other the color of a darkened animal horn.

These vivid descriptions of urine show just how sensory a task physicians were undertaking when inspecting patients’ samples, with uroscopy texts encouraging all sorts of behavior at the bedside: testing the viscosity of the urine and any particles suspended within, grading its smell or evaluating its sweetness or bitterness. Shaken, stirred, sniffed, even tasted, urine was reified in such flourishing trees, turned from effluvia to a careful diagnostic tool.

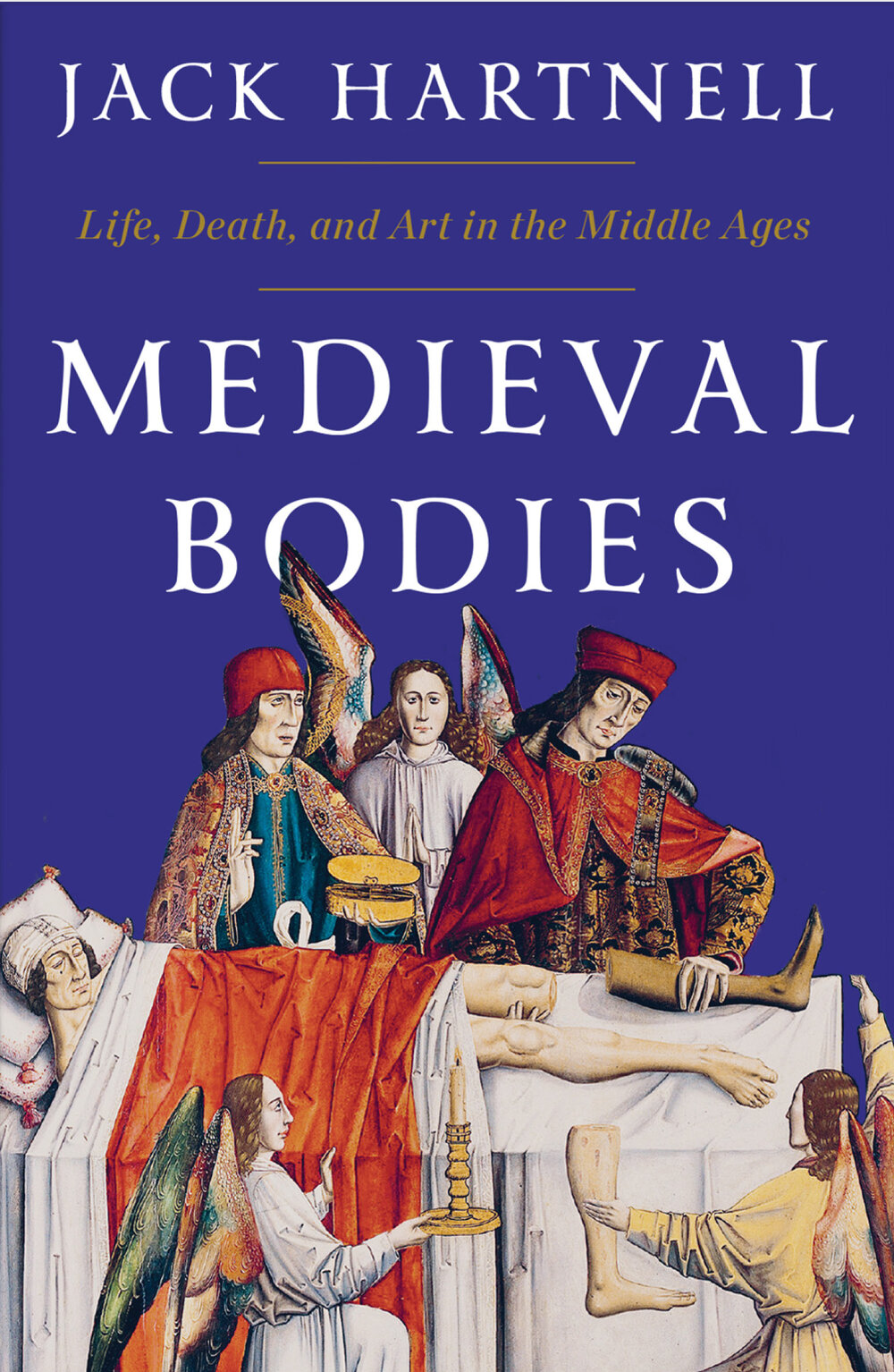

Excerpted from Medieval Bodies: Life and Death in the Middle Ages. Copyright © 2019 by Jack Hartnell. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.