Dance tunes are always right.

—Dylan Thomas, 1936

Dancer and musicians, earthenware with pigment, Han dynasty (206 B.C.–A.D. 220). © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Charlotte C. and John C. Weber Collection, Gift of Charlotte C. and John C. Weber, 1994.

In 1984 the filmmaker Chen Kaige released his directorial debut, Yellow Earth, generally credited with changing the face of Chinese cinema. Set in the northwestern province of Shaanxi in the spring of 1939, the film depicts a soldier from the Communist Party’s propaganda department tasked with collecting peasant folk songs. The opening scene follows him trekking through a dry, barren plain, where at first all that can be heard are the whistling of wind and the cawing of a bird. A human voice begins singing in the distance; the soldier quickly takes out a small notebook and starts scribbling. The voice suddenly vanishes, leaving only the wind to be heard still blowing through the empty fields. Sounds of nature yield to human sound, which recedes back into sounds of nature.

This CCP soldier is no folklorist; he’s not undertaking academic study. He is engaged with a Chinese tradition whose political significance stretches back millennia. In premodern China, every student was required to read a core set of Confucian classics. One of these was the Classic of Poetry, a collection of 305 poems dating from the eleventh through seventh century BC. During the Han dynasty, no later than the first century, a preface to the work was formulated that gained enormous stature; called the “Great Preface,” this text discusses how music could provide insight about the society in which it was produced.

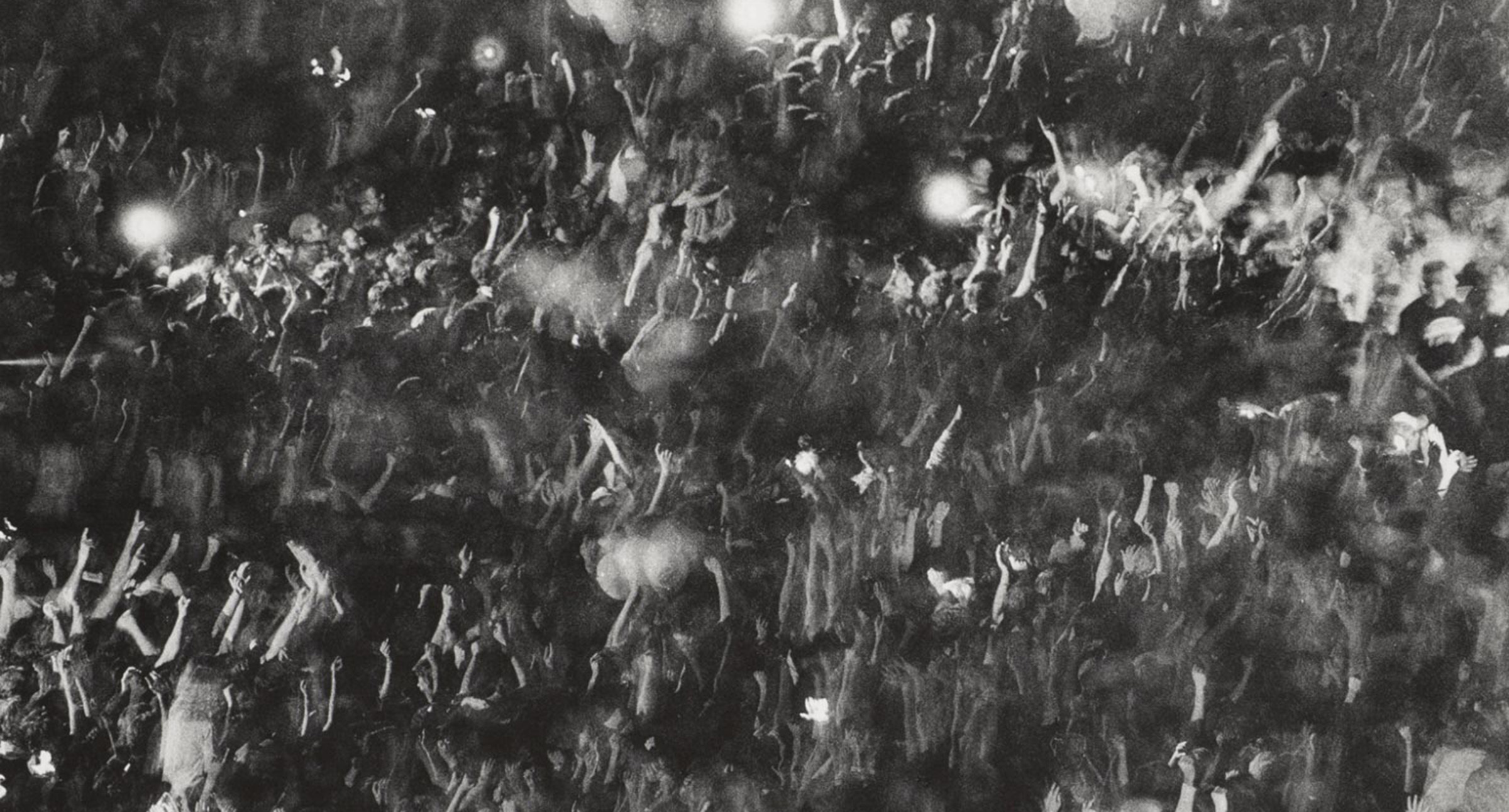

Rolling Stones Concert, New Orleans, by Burk Uzzle, 1982. © Philadelphia Museum of Art, purchased with the Lola Downin Peck Fund and with funds contributed by Mr. and Mrs. John Medveckis, Douglas Mellor, Ross Watson, and other donors, 1984.

The collected poems in the Classic of Poetry are understood to have originally been sung to music—the title is sometimes translated as the Book of Songs—and the canonical statement on poetry in the preface is closely bound with a discussion of music’s nature and function:

Feelings emerge in sounds; when the sounds have patterning, they are called tones. The tones of a peaceful age are serene and happy, indicating its government is well-run; the tones of a chaotic age are bitter and angry, indicating its government is off course; the tones of an age going to ruin are filled with sadness and brooding, as its people are in difficulty.

The difference between sound (sheng) and tone (yin) is the presence of patterning. The cawing of birds and the whistling of wind, or the sobbing at a funeral, may be considered sounds, but a dirge sung at the funeral belongs to tones. Music is both nature (based in feelings) and culture (with patterning). Even more important, music is closely associated with words—that is, song lyrics. It’s also associated with governance. An old legend about ancient kings articulates this unique belief in the political—not just aesthetic or philosophical—importance of music. According to the story, the kings would send their officers to the villages, collect the songs of the common folk, and bring them back to the court, believing the songs to be signs and symptoms that can tell the king about the mood of his people. If it is happy, the king can rejoice with them; if it is distressed and resentful, the king must either reform his government or face certain ruin.

This legend was believed—and is still believed by many—to be the origin story for a section in the Classic of Poetry called “Airs” (feng). This section contains 160 poems, categorized into fifteen different regions representing the feudal domains of Zhou dynasty China. These poems occupy a position in Chinese literary tradition similar to the Homeric epics in the Western tradition. They show how music manifests the condition of the empire and can in turn impact it: each geopolitical region has its own music; the king, ruling from the political center, listens to all of them and, if he is wise, knows how to interpret them and govern accordingly.

These songs of “Airs” are lively ballads that supposedly originated among the common folk. They were the popular songs of their day and feature ordinary men and women singing of love, the pain of separation and abandonment, romantic longing, the toil of the fields, the hardship of travel, and the homesickness of soldiers on prolonged military campaigns. Though many were as likely to be created by court musicians as by peasants and soldiers, it is the belief about their folk origin that matters.

In Confucianism, music is regarded as one of two cruxes for living a civilized life. The other crux is rites. These are seen as theoretically divergent: rites separate people by creating social distinctions, while music harmonizes a community to bring people together; rites keep people civil but risk alienating them from one another, while music unites people but risks turning them loose and dissolute. Both are seen as fulfilling important roles in maintaining the social order, and the Confucian ideal is a perfect balance of the two.

On a practical level, however, music and rites are often joined together in the performance of ritual music, which fills the other two sections of the Classic of Poetry—odes and hymns performed at state rituals, including sacrifices made to Heaven and Earth and to ancestors and dynastic founders. This music is grave and solemn, representing grand historical events in formal, stilted language.

There is a tension between serious ritual music and lively popular music in the content of the Classic of Poetry, just as there was always tension between the two in social life in traditional China. The Marquess of Wei, the lord of a feudal domain in the Zhou, was said to have once fallen asleep during a performance of ritual music but woke up to the playing of popular music. He was deeply embarrassed upon being called out by his disapproving ministers, who saw the marquess’ involuntary reaction as an indication of his moral failings and inadequacy as a ruler. Herein is the paradox of the “folk songs”: they are considered precious as the voices of the commoners but are also dangerous, for they may beguile the ruler with their plain language of mood and desire. A king, if not wise, might prove to be a bad interpreter of a song-poem of romantic longing and make a faulty political choice. Perhaps lyrics about the sorrow of separated lovers fail to inspire the king to call off a military campaign—which would take husbands away from wives—but instead seduce him with eroticism and drive him toward licentiousness. Music interpretation could have dire dynastic consequences.

Around the time the “Great Preface” was being formulated, a monarch created an institution that put this musical aspect of political ideology into imperial practice. The institution was the Yuefu, the “Music Bureau.” The monarch was Emperor Wu of Han, an ambitious, energetic ruler who ascended the throne as a teenage boy in 141 BC and reigned for fifty-four years, a record not to be broken for more than eighteen centuries. During his rule, he centralized state power, expanded the territories of the empire, opened up the Silk Road and sent many missions to Central Asia, adopted Confucian doctrine as mainstream ideology, and was an ardent lover and patron of musical and poetic arts. Around 120 BC he ordered the establishment of the Music Bureau.

There is not much information about the workings of the bureau in extant historical sources; what little we know about it comes from terse statements made about the office and its leader, whose title, director of music, was apparently coined by the emperor and literally means “commandant of harmony.” According to the historian Ban Gu (32–92), the bureau was in charge of “collecting song-poems [during the day] and having them rehearsed at night.” The song-poems were reportedly “ballads selected from the lands of Zhao, Dai, Qin, and Chu,” encompassing all four directions of the empire. Music, like state power, was centralized in the imperial court, and in turn it was seen as a unifying force embodying all regions of the empire.

Before Emperor Wu established the Music Bureau, court music had fallen under the aegis of court ritualists. This new office now institutionalized imperial music and for the first time gave it an independent identity. Although the office did produce ceremonial music for state rituals, an equally important purpose was to provide well-managed imperial entertainment. As such, it was appropriately led not by a hoary ritualist versed in ceremonial music but by a young, handsome, talented castrato musician named Li Yannian, who made for a rather extraordinary and unconventional appointment.

Li Yannian was from a family of professional entertainers. When he was a young boy, he had received the punishment of castration for some offense. Being a castrato led him to career choices beyond his family’s usual orbit: as a eunuch, he found employment in the Directorate of the Palace Kennels, even though his true gift was apparently in music rather than in breeding and caring for the imperial hunting dogs. While Li Yannian was employed there, Emperor Wu met his sister, a stunning beauty and consummate dancer, and became smitten with her. Soon, Lady Li bore the emperor a son, cementing her eminent status in the harem. Meanwhile, the emperor came to appreciate Li Yannian’s musical talent deeply. The boy became the emperor’s favorite musician—as well as the emperor’s lover.

Having been castrated at a young age must have given Li Yannian, already a good-looking boy, a striking appearance (as we now know, the loss of testosterone can result in unusually long limbs and make a castrato taller than average). It was not a known custom in premodern China, as it was in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Italy, to castrate a talented young boy singer to keep his prepubescent voice. But we may well imagine how Li Yannian’s accidental acquisition of a voluptuous and sublime voice as a castrato might have greatly contributed to the charm of his singing. “All mouth and no trousers,” goes the saying—yet his fame came even more from his gift as a composer.

The Pic-Nic Orchestra, by James Gillray, 1802. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1917.

At the emperor’s commission, Li Yannian produced new music for state rituals, which were constantly being invented by Emperor Wu, who was obsessed with worship of the empire’s deities. (Neither these deities nor his devised rituals, however, were necessarily approved by orthodox-minded Confucian ritualists.) Li Yannian was apparently at his best in the composition of “new fancy tunes” that represented a “permutation” of serious ritual music (yayue, literally “elegant music”). He had modern, catholic, unconventional tastes: he not only reinvented contemporary regional melodies but also embraced foreign influences. He was famous for creating twenty-eight tunes inspired by the Central Asian music of what were called the Western Regions, astride the Silk Road. Even when the music was lost in later times, some of the tune titles endured and became established titles in the poetic genre known as yuefu, after the bureau.

At the peak of his career, Li Yannian would “sleep and rise with the emperor” and had his ear when recommending associates to offices. But the Li family’s good fortune did not last very long. Li Yannian’s sister died young, and the emperor’s favor faded. When Li Yannian’s little brother was caught having an affair with a palace lady, both brothers were executed, and, history tells us, “the entire family was exterminated.”

Stern Han moralists, including the Confucian ritualists, must have resented Li Yannian’s rise to stardom, his unorthodox musical creations, his sexual proximity to the emperor, and his political influence. Rumors about his power to bewitch the emperor with his musical gift had begun early. Although contemporary sources indicate that he was summoned to imperial audience only after the emperor became enamored of his sister, the moralistic historian Ban Gu claims that Li Yannian had enjoyed imperial favor before his sister did, and hints, not so subtly, that Li had in fact manipulated the emperor’s desire with his song—the only song attributed to him whose lyrics have survived to this day:

In the north there is a fair lady,

She stands alone beyond compare.

She glances once, a city falls,

A kingdom falls when she glances again.

Surely you know that a lady so fair,

She for whom cities and kingdoms fall,

Will never be found again.

Emperor Wu reportedly listened to the song in rapture and, after Li Yannian finished singing, heaved a great sigh: “Can it be possible to find such a fair lady in this world?” Thereupon Princess Pingyang, the emperor’s ever-solicitous sister, told him about Li Yannian’s sister. Emperor Wu had her brought to him, found her to be indeed just as beautiful as described in Li Yannian’s song, and became infatuated.

Ban Gu’s account portrays Lady Li as a calculating woman who wanted to keep the emperor’s affections only in order to win favors for her family. Li Yannian’s song is represented as a skilled artist’s careful staging of his sister’s beauty, an advertisement to arouse the emperor’s desire. The beguiling words—Stands alone! Beyond compare! Will never be found again!—appealed to the grandeur-loving and egotistic emperor. No doubt the words were made even more powerful by music and the castrato’s sublime voice.

But if this story is to be believed, then Emperor Wu would seem to have completely missed a darker interpretation of the song, intimating that cities and kingdoms can fall for such a fair lady. The description echoes lines from the Classic of Poetry: “A smart man constructs a city, / A smart woman makes the city fall.” A wiser ruler would have heard a different message.

In Chinese historiography, where the passing of moral judgment is considered the sacred duty of a historian, and where the causality of events is always represented in moral terms, Li Yannian’s tragic ending must be seen not just as a “fact” recorded by a dispassionate historian but as a stern lesson to those born later. Despite Li Yannian’s obvious gift and eminent competence in his position as commandant of harmony, his story is one of censure and warning—about the foolishness of a besotted emperor, and about what happens when someone upsets the balance between “elegant music” and popular music.

Emperor Wu’s Music Bureau didn’t last long; it was abolished toward the end of the Western Han dynasty by Emperor Ai (reigned 7–1 BC). And though the term yuefu was afterward applied, somewhat anachronistically, to later court musical establishments, it was the generic meaning of the term that proved to be long-lasting and influential.

The god of music dwelleth out of doors.

—Edith M. Thomas, 1887In the sixth century, nearly six hundred years after Emperor Wu, “yuefu poetry” became an established literary category referring both to anonymous songs recorded in court music repertoires and poems composed by known men of letters. A yuefu poem’s speaker was usually a dramatic persona—an abandoned wife, a homesick traveler, a heroic warrior—understood to be someone other than the poet. Such works increasingly lost any connection to music and became purely textual. By the eleventh and twelfth centuries, yuefu also referred to a new form of song lyrics known as ci; these, too, began as anonymous lyrics meant to be accompanied by music and sung at parties but became literary texts written by named authors and completely divorced from song.

Although music itself became less and less central to the form, many yuefu poems retained a link to the Classic of Poetry via its theory that songs told the mood of the people. The ninth-century poets Bai Juyi and Yuan Zhen advocated the use of yuefu to represent the grievances of the populace. Their yuefu poems, however, did not follow a tradition of established titles and themes. The works became known as New Yuefu.

Despite the poets’ anguished protests, not all New Yuefu was great poetry. But one work by Yuan Zhen deserves mention: a meta-yuefu titled “Musicians in the Standing Section.” The title refers to an establishment created for popular music in the imperial court of the Tang dynasty. The establishment divided performers into a Standing Section and a Sitting Section, with the latter considered more valued. Yuan Zhen’s poem laments mediocre musicians in the Sitting Section being sent down to perform in the Standing Section, and then the mediocre musicians in the Standing Section being further sent down to perform in the establishment for “elegant music,” that is, serious ritual music. He complains about the imperial love of popular music—whose “aberrant sounds” he believes can manipulate the ears and corrupt the mind—and argues that by valuing it above ritual music, the dynasty is committing a moral deviation responsible for its own decline. He also criticizes the mixture of Chinese and foreign tunes in court musical performances, regarding this as an omen of a mid-eighth-century rebellion by an ethnically non-Chinese general that had devastated and weakened the Tang empire. Yuan Zhen choosing to mount his attacks on hybrid popular music in a yuefu poem is rather ironic—the genre’s name came, after all, from Li Yannian’s Music Bureau, which held those values in the highest esteem. “Musicians in the Standing Section” may, in this way, be seen as the ultimate subversion of its own tradition.

Portrait of a Woman, Said to Be Madame Charles Simon Favart, by François Hubert Drouais, 1757. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Mr. and Mrs. Isaac D. Fletcher Collection, Bequest of Isaac D. Fletcher, 1917.

Perhaps, in the end, Confucian ritualists had good reason for placing such weight on music and worrying so much about its effects. Music is fluid and transcends the borders of culture and ethnicity. Moralists cannot control what one hears in a song; it moves its listeners and has the power to carry them away. The term feng—the Chinese word for “Airs,” that popular-song section of the Classic of Poetry—also means “wind” as well as “influence.” With this in mind, the opening scene of the film Yellow Earth takes on new meaning. The human voice does not really vanish but becomes one with the wind echoing on the barren plain with a single tree standing on the horizon: it sways.