Those who go overseas find a change of climate, not a change of soul.

—Horace, 20 BCThe Right to Leave

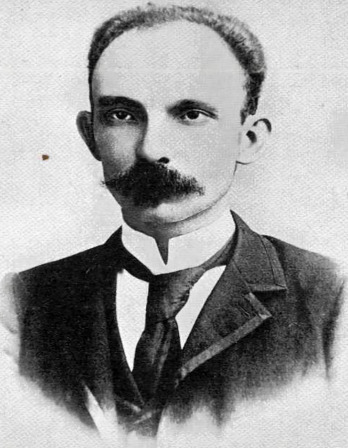

Thomas Jefferson was a proponent of open migration. But who qualified as a refugee?

By Stephanie DeGooyer

William Gropper’s America, Its Folklore, by William Gropper, 1946. David Rumsey Historical Map Collection (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0).

In 1816 an American lawyer named J.F. Dumoulin wrote Thomas Jefferson a letter to thank him for his hospitality during a recent visit to the former president’s Monticello plantation. As a token of gratitude, Dumoulin enclosed a treatise he had written about naturalization and expatriation. The essay denounced Britain for holding fast to the feudal doctrine of perpetual allegiance, which denied individuals the right to change their nationality. In his reply Jefferson praised Dumoulin, whose opinions on emigration closely matched his own. Why would any man, he wrote, “feel any obligation to die by disease or famine in one country, rather than go to another where he can live?” Every person has just as much “right to live on the outside of an artificial geographical line as he has to live within it.”

With hindsight, historical ideas often appear commonsensical or even passé. Twenty-first-century students look back on the suffrage movement as merely the imperfect beginning of progressive agitation for women’s rights. They see the first UNESCO statement on race, which disclaimed scientific racism in 1950, as banal and insufficient in the age of Black Lives Matter. Antifascist movements in the 1930s seem the obvious and necessary response to Hitler and Mussolini, what any self-respecting person would have done under the circumstances.

Jefferson’s ideas on migration have the opposite effect. That an American founding father and president would assert the arbitrariness of national borders and champion the right of individuals to live anywhere strikes many of us as deeply surprising. The hard-line immigration stances of the three most recent American chief executives—and Jefferson’s known record as a slaveholder—add to this disbelief. But Jefferson was a lifelong proponent of what today is known as open borders. He scaffolded American independence on this principle, and as president he acted according to the view that any impediment to an individual’s mobility was a desecration of the American republic itself.

More than a century later, the United Nations would stake the future of the postwar international order on this same idea. The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights announced an individual’s “right to leave any country, including his own” and held that “no one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality nor denied the right to change his nationality.” After World War I, programs of ethnic cleansing in the Near East and the rise of fascism in Europe drove millions of people out of their home countries. The UDHR was a Herculean international effort to protect refugees who had found themselves homeless and adrift across Europe. The problem is the UDHR lacks a legally binding and obligatory force on sovereign states. The United States has often opted out of its recommendations, initially refusing, for example, to ratify the United Nations 1951 Refugee Convention and instead passing its own Refugee Relief Act to focus on refugees from communist states. Jefferson’s defense of a right to leave thus appears all the more remarkable. He advocated for a universal right to migrate while in the process of establishing America as a sovereign nation.

Jefferson’s advocacy for open migration also appears surprising because the history of American immigration has mostly been a story of restriction. In the nineteenth century, there was mass migration of people from China who came to America during the California gold rush or to work on the transcontinental railroad. Hostility toward immigrants grew. The government enacted the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act and the 1924 Immigration Act, which introduced the first immigration bans based on race and country of origin and openly prioritized white immigrants from Nordic countries. Even after these laws were effectively repealed in 1965, immigration law in the United States continued to be predicated on a hierarchy of desirable and undesirable immigrants. As historian Mae Ngai has shown, when immigration from the Eastern Hemisphere was reopened in the 1960s, restrictions shifted to target migrants from Mexico and other Central American countries.

Pigeons and sparrows, illustration from Kitagawa Utamaro’s Myriad Birds: A Playful Poetry Contest, 1790. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, H.O. Havemeyer Collection, bequest of Mrs. H.O. Havemeyer, 1929.

The comparative absence of overtly racist immigration laws before the nineteenth century has left room for a founding father such as Jefferson to represent a lost American ideal. Libertarian thinkers have been especially quick to idealize American history in their primarily economic calls for open borders. Bryan Caplan, a libertarian economist at George Mason University, argues that “the U.S. had hundreds of years of open borders, and it was a country…Of course you can have open borders and be a country.” Shikha Dalmia, a columnist for The Week and self-professed “progressive libertarian,” writes, “America had relatively open borders until the early twentieth century. The political conversation on immigration has become too poisoned for us to return to anything approaching that now or in the foreseeable future.”

It is not only libertarians who hold a torch for the past. After the election of Donald Trump, many liberals sought to remind Americans that their country had once been more welcoming of immigrants. “As the founding fathers recognized,” wrote Aaron Freedman in The New Republic in 2019, “open borders are the key to making America great. Engaging with this history, contemporary Americans may well come to that conclusion, too.” The same year, Farhad Manjoo explained in his New York Times column that “America’s borders were open for much of its history—if your ancestors came here voluntarily, there’s a good chance it was thanks to open borders.”

Scholars of open borders avoid these bromides. Instead they train their insights on the implications of violent borders in the contemporary globalized world. But even they make slippery and ambiguous references to history. The political scientist Joseph Carens has argued for open borders by drawing an analogy with medieval England, arguing that “reformers in the late Middle Ages objected to the way feudalism restricted freedom, including the freedom of individuals to move from one place to another in search of a better life.” Modern border control also ties people to the land of their birth. And so Carens asked, “If the feudal practices protecting birthright privileges were wrong, what justifies the modern ones?” That is, if we can agree that the American revolutionaries were right in opposing England’s migration restrictions, how can we justify restricting movement to America today?

Jefferson was radical in many ways. For him nationality and citizenship were voluntary choices rather than innate identities. In 1774 he sent a draft to the Virginia delegates of the first Continental Congress arguing that the American colonies had a natural right to separate from Great Britain. In a republished version, Jefferson spoke of “a right which nature has given to all men, of departing from the country in which chance, not choice, has placed them.” Later, in his autobiography, he would recall that nobody at the time supported his emigration doctrine because it strongly undermined the right of the British government to determine the nature of allegiance in the colonies. Even other Enlightenment thinkers sympathetic to the idea of open migration, such as the political philosopher John Locke and the legal theorist Emmerich de Vattel, did not hold such radically individualistic views on the subject.

After the American Revolution, Jefferson continued to push reforms in favor of free immigration within the colonies and across the Atlantic. As a leader of the opposition, he was a staunch critic of the Alien and Sedition Acts, a set of laws Congress passed in 1798 aimed at suppressing French and Irish immigrants believed to be faithful to France. His “Kentucky Resolution,” which is today remembered for its controversial articulation of the importance of states’ rights, was written as a critique of the unconstitutionality of the Alien and Sedition Acts.

Most radically, Jefferson believed emigration was a right that America should protect even if it meant losing its own citizens. In 1806 Jefferson wrote to Albert Gallatin, the treasury secretary, to defend the right of American citizens to abandon their nationality. Congress, he wrote, “cannot take from a citizen his natural right of divesting himself of the character of a citizen by expatriation.”

When Jefferson became president in 1801, he used his first Annual Message to Congress to remind fellow citizens of America’s lasting importance as an asylum. America came into existence because emigrants exercised their freedom to form a country of their own. The fight for this freedom was not only a convenient origin story—it was America’s perpetual purpose. “Shall we refuse the unhappy fugitives from distress that hospitality which the savages of the wilderness extended to our fathers arriving in this land?” Jefferson asked. “Shall oppressed humanity find no asylum on this globe?” In 1817 he wrote a letter to the explorer George Flower referring to America as “another Canaan” where people could always be “received as brothers.”

Yet Jefferson’s views on emigration were formed in a dramatically different context from our own, in a nation seeking ideological justification to pry itself free from the clutches of Great Britain and establish itself as a sovereign country. It was convenient for an architect of the American revolution to hold the view that emigration was an unlimited right. Jefferson could argue that even though the American colonists had once given their consent to the British king and had adopted English common law as their own law, they never irrevocably gave up their freedom to leave British political society. When the British king violated the trust of the American colonists by pursuing parliamentary actions against them, the colonists were within their natural rights to break ties with their mother country.

A smaller, less historically consequential crisis would also shape Jefferson’s philosophy on emigration. During the Napoleonic Wars (1803–15), the British Royal Navy impressed many thousands of American sailors into service aboard British vessels. Bands of British soldiers known as press-gangs barged into seaport taverns and docked merchant ships looking for American soldiers to force into military service on behalf of the Crown. The British argued they had the right to conscript Americans against their will under the common-law principle of nemo potest exuere patriam, or perpetual allegiance, which held that those born under the British Crown owed allegiance to Britain in perpetuity. Nothing about the American independence won by the revolution could change or cancel this original obligation.

Like most Americans, Jefferson was outraged. As president he tried several times to negotiate trade treaties with Great Britain to end the practice, to no avail. The War of 1812, declared three years after Jefferson left office, was waged against the British partly over the continued impressment of American sailors. The practice was finally ended in law by the Expatriation Act in 1868.

The treatise that Dumoulin sent to Jefferson was written as ammunition for the American side of the debate about impressment. In it Dumoulin gave a long-winded defense of expatriation as one of humanity’s most sensible rights. Ancient Rome, he reasoned, would never have subscribed to the doctrine of perpetual allegiance. Had it done so, it could not have counted luminaries such as Cicero, Seneca, and Marcus Aurelius among its citizenry. (Dumoulin was wrong about Marcus Aurelius’ origins, which were fully Roman.) The same was true of early modern Europe; if perpetual allegiance had been law, Spain could not have claimed the Italian-born Christopher Columbus’ discovery of the Americas as its own. Perpetual allegiance was a relic of the gloomy and superstitious feudal age, Dumoulin argued. It had no credibility in the enlightened world.

Jefferson agreed. He thought no ties could permanently bind a man to the country of his birth. This was true whether a man was an eminent explorer or a poor farmer. And it remained true whether that man had previously agreed to be a member of the political society or was born into a new one. Yet these defenses of a right to migration, from Dumoulin, Jefferson, and many others, were ultimately attached to the perception that this right was under immediate threat. Would Jefferson have protested as loudly if the British had not doubled down on the perpetuity of national allegiance?

There is not much reason to believe he would have. In his book Notes on the State of Virginia, written during the American Revolution, Jefferson speculated that America’s population would double every twenty-seven and a quarter years. At that rate, if the country continued to rapidly increase its population through migration, then within ninety-five years the country would have grown too large and disparate. Jefferson prophesied that migrants fleeing other tyrannical regimes would come to America, where they would bring foreign traditions, unruly behavior, and non-English languages. These new migrants would “infuse” into America “their spirit, warp and bias its direction, and render it a heterogeneous, incoherent, distracted mass.” Trading philosophy for demography, Jefferson argued that America should not continually abide by the principles of open migration he advocated.

Even in his own time, Jefferson maintained a very circumscribed idea of who could rightfully qualify as an immigrant in America. This can be hard to see because when we read the words refugee and asylum in his writing, we filter that language through meanings inherited from twentieth-century international law.

Take the word refugee. According to the 1951 Refugee Convention, a refugee is anyone who is “unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.” This policy-based definition was originally designed to clarify the legal entitlements owed to European refugees seeking asylum after the world wars. Since the 1960s it has served as the United Nations’ guiding policy for the reception of all refugees.

Whole nations have melted away like balls of snow before the sun.

—Dragging Canoe, 1775Before World War I, however, the word refugee was not linked to a set of legal entitlements. In the early eighteenth century, refugee referred specifically to the hundreds of thousands of French Huguenots who fled France in the late seventeenth century after Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes, which had for centuries granted religious tolerance and freedom of conscience to Protestants living in France. In the 1790s the word still designated only European religious refugees. Forty thousand British loyalists, Quakers, and Germans who were, like the Huguenots, displaced by conflicts in their home countries and fled from the United States to Canada were called “American refugees.”

In Jefferson’s time refugees were understood to be of European origin and of the Protestant faith—characteristics that made them desirable immigrants. Religiously persecuted refugees were the ideal conscripts because they could maintain the American colonies as a shared Protestant enterprise. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, the British government sent refugees from Germany (known as the “Poor Palatines”) to Ireland and the American colonies to bolster the presence of Protestants and labor for a poorly devised scheme to make tar and pitch for the British navy. New York was chosen as the site for the Palatine emigration to North America because the frontier against the French was thought to be weak, and it was hoped the refugees would provide a buffer against the indigenous population at the far western periphery of the European settlement.

Many of the refugees who sought a haven in America in the eighteenth century were welcomed as a part of the settler-colonial project to displace Native American populations and exploit the labor and lives of African slaves. The colonies viewed settler refugees such as the Huguenots and Palatines as welcome recruits because they helped maintain a large white and Protestant presence in the colonies, which was thought to be essential for tamping down the looming threat of slave insurrection and preventing a slave majority. The refugees were offered land, political rights, and religious toleration in exchange for their labor clearing land. Their ability to obtain freedom and land for their service set them apart from the enslaved. Enslaved people were believed to be uniquely suited for the harshest labor in the colonies, while refugees were put on a less punishing and even regenerative path that eventually transformed them into landowning settlers.

A Wagon Train on the Plains, Platte River, by Worthington Whittredge, c. 1866. Photograph © Christie’s Images / Bridgeman Images.

In the early republic era, American asylum continued to be defined by racial and religious exclusiveness. As legal scholar Aziz Rana has shown, at the beginning of North American colonization, unpropertied settlers and refugees occupied the same continuum as slaves and Native tribes, as subjects of a coercive royal authority in England. Over time colonial administrators began to expand privileges for white Protestant immigrants, as they wanted to ensure a large and willing population that could destroy their Catholic and indigenous enemies. It was this sense of a shared Protestant mission that entrenched the idea, carried into the American Revolution, that only Protestants could be the beneficiaries of liberty and self-rule. With a few small exceptions, only Protestants were viewed as having the discipline, work ethic, and spiritual rigor to rule themselves. None of this changed after the American Revolution. The political liberties promised by colonial administrators to refugees and colonists in exchange for their separation from Great Britain further differentiated white colonists from enslaved people and Native populations.

After colonists hardened themselves against British tyranny, they began to direct their self-preservation impulses toward those also perceived to be threatening their liberty at home: the Indians and emancipated slaves whose labor and land were fueling the growth and independence of the colonies. A fiction needed to be created and maintained to deny them the same natural rights the colonists were fighting for, and that fiction needed to become law. In 1790 the United States passed its first Naturalization Act, codifying who could become an American citizen. This legislation legally enshrined what had always been an American practice: only white and male persons could become political participants in the nation, and only these persons were capable and deserving of economic and political independence.

This is the background against which Thomas Jefferson’s universalism was defined. When Jefferson spoke of “oppressed humanity” and “unhappy fugitives,” he, like his countrymen, had a very particular type of European refugee in mind. Jefferson’s version of revolutionary asylum was therefore entirely consistent with the violent dispossession and racialized exclusion that have marked immigration since the nineteenth century. Borders only appear more open in Jefferson’s day because there were no ports of entry for the collection of passports or visas to permit entry. The absence of a legal bureaucracy for sorting and processing immigrants did not, however, mean that all were welcome. It simply means that exclusion is easier to see when immigration criteria are blatantly racist.

Historian Jill Lepore observes that America is defined by contradiction. The United States, she writes, is “a nation that declares most of the peoples of the world ineligible for citizenship and yet also describes itself as an asylum.” For Jefferson, however, there could be no contradiction between his description of America as a land of the free and his ownership of more than six hundred slaves. When he championed the United States as an asylum for the oppressed and downtrodden, he was not thinking of the Black Africans and indigenous peoples denied the advantages of naturalized citizenship. When he opposed John Adams’ lengthening of the residency requirement for naturalization, he did not protest its original racial qualification of “free white persons.” There was no hypocrisy, because Jefferson saw asylum in limited terms, not in the expansive, universal way some people frame it today.

If there is one useful takeaway from Jefferson’s argument about a right to leave, it is that American citizenship was originally designed to be a more flexible bond than allegiance. Americans fought Britain over the idea of perpetual allegiance, claiming a loosened hold between birth and citizenship. Many people today conceive “Americanness” as a patriotic and nationalist kinship to the land of one’s citizenship. To be American is to pledge allegiance to America, to owe it undying love and respect. Being born in America is thought to establish a greater relationship to the country than for those born elsewhere. Yet new immigrants and naturalized citizens are expected to express gratitude and a sense of obligation to their new country, not to mention pass naturalization tests that query them on aspects of American history native-born citizens would never be expected to know.

Jefferson fought against all of this. He believed we should be able to cast off the country in which we are born when we feel that a bargain with our sovereign nation proves to be a bad one. But while Jefferson encouraged the bonds of allegiance to slacken for Americans, he did not ever—except maybe in his criticisms of the Alien and Sedition Acts—question the integrity of American sovereignty itself. His view of a right to leave was entirely commensurate with America’s right to define who it does and does not want within its geographical borders.

The times have changed. We are no longer worried that the United Kingdom will exercise an ancient right to demand the allegiance and military service of new American residents (unless we count the stateside media coverage of Prince Harry’s acrimonious divorce from the royal family and move to Southern California). And most countries today do not try to prevent the emigration of their people. In fact, as became evident in Europe after World War I, many states evict their citizens with little concern for their welfare or return. For Jefferson a right to leave was important for Americans because Great Britain did not want to recognize the independence of the United States. But this right, which was of extreme importance to the colonies seeking to separate themselves from Great Britain, does not carry the same ideological weight today.

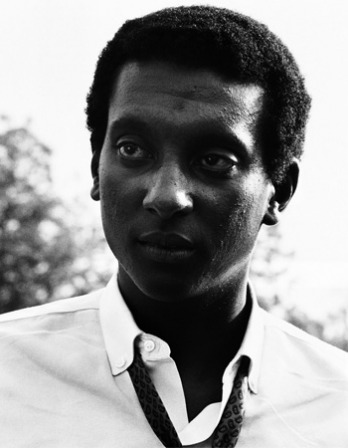

These days, migrants do not want the right to continually move or abandon their nationalities. As they flee war-ravished nations, environmental disaster, and extreme poverty, they clamor for a right to be received. They want the choice and freedom to determine the best life for themselves and their families. They want, through the immigration-advocacy groups that represent them, progressive paths to citizenship: extensions of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals and Temporary Protected Status, a higher annual cap for refugee admissions, amnesty for undocumented workers, the right for migrant workers to unionize, an end to arbitrary reentry bans, greater independence for immigration courts, and the abolishment of Immigration and Customs Enforcement. They want an end to the endless waiting for entry, an end to the shifting rules that make it impossible to claim asylum, and an end to the militarized border patrol that uses lethal force to keep migrants out.

What good is a right to leave if nobody wants to let you in?

America cannot be redeemed by a return to its original self. The founding fathers cannot help us imagine what a truly unbordered world, with the right of all individuals to move and live freely, might look like. If anything, we need complete severance with the past to make such ideas possible. But this is something Jefferson would have welcomed. Just as he advocated for revised terms of allegiance between citizen and state, he also called for a rewriting of the U.S. Constitution every nineteen or twenty years. The United States, he argued, reinterprets and redetermines itself with each new generation; it is a future-oriented country not slavishly devoted to tradition. When Jefferson estimated in 1781 that America would grow too big if it continued to openly admit migrants, he presumed that the Constitution would also change over time. Just as Jefferson knew America would not be the same nation in the future, we are not obligated to replicate its past.