Time’s ruins build eternity’s mansions.

—James Joyce, 1922Captain Clock

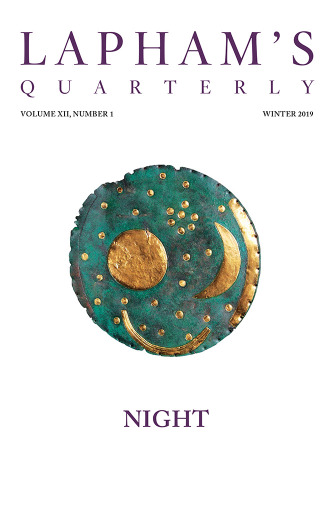

From overtime to downtime, spending time to saving time, the uses and abuses of our minutes and days.

By Lewis H. Lapham

Still Life with a Skull and a Writing Quill, by Pieter Claesz, 1628. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund.

If both what is before and what is after are in this same “now,” things which happened ten thousand years ago would be simultaneous with what has happened today, and nothing would be before or after anything else.

—Aristotle, c. 330 bc

Aristotle goes on to suggest that if time past is no more, and time future is not yet, time undoubtedly is of the essence, but the essence of time is neither here nor there—like God and Peter Rabbit, a work of man’s imagination. Let the whereabouts of time be anybody’s guess, its motive and intent matters of conjecture, and the distance between the now and the then is whatever length of measurement or metaphor serves the conscience or the interest of its finders and its keepers.

Across the two millennia since Aristotle posed the problem, no solution has been forthcoming from the sciences, the bond markets, or the arts. This issue of Lapham’s Quarterly collects the further observations of physicists and philosophers, of astronomers and accountants, poets and historians, but none can say for certain that they know what it is they’re looking for. Agreed that time shows or hides itself in the immensity of the restless atoms that constitute the universe—in the rising and setting of the sun, the movement of tides and the migration of birds, the opening of flowers and the closing of banks—they divide as to whether the past is dead or alive, the future a beginning or an end, time wandering around in circles or moving on and out along a straight and steady line.

If the perception of time is the passage of time, and the passage of time the perception of time, wherefrom the authority of clocks? The question recurs throughout the pages here fleetingly in hand, and I can remember asking it as a child at a loss to know why sometimes an hour on the clock was as long as a Sunday in the rain, at other times so short as to have gone by without a ticking or a tock—why time seemed to pause or stop on a bar of music or a field of play.

Introduced at the age of eight to the concept of light traveling in space at the rate of 186,282 miles per second with all of the world’s history (the settings and dramatis personae) still intact, I’ve yet to be relieved of the suspicion that Genghis Khan and Queen Victoria are somewhere out there still, light years away, but visible from distant star systems deploying telescopes of science-fiction magnitude. By the time I was twelve I was reading history books in the way that William Golding tells of reading archaeological digs on the downs of southern England, the “glossy darkness under the turf…aglow with every kind of picture”—of Stone Age Druids and medieval knights, pagan kings and Christian saints. Time I understood to be a wonder that never ceased, in both the present and the past, and I was content to let it come and go where and how it pleased, to watch it boldly sail with every ship departing San Francisco Bay, see it creeping softly back concealed in fog.

Bison at Maxwell Game Preserve, Roxbury, Kansas, December, by Terry Evans, 1981. Chromogenic print. © Terry Evans, courtesy of the artist and Yancey Richardson.

The taking time to be everywhere abundantly at once accords with the thinking of Henry David Thoreau at Walden Pond in the summer of 1845, unable to “afford to sacrifice the bloom of the present moment to any work, whether of the head or hands…I minded not how the hours went,” because all of them were proofs of his “incessant good fortune.” At age fourteen I was well acquainted with the losing track of time while looking in amazement at most everything in sight, familiar with the truth as later told by James Thurber: “It is better to have loafed and lost than never to have loafed at all.”

The attitude infuriated my father, a banker descended from a line of seventeenth-century New England merchants, who regarded idleness as stupidity and sin, both faults to be corrected by paying strict attention to the cost of movie tickets and the wisdom of

Benjamin Franklin—“Remember that time is money,” or, “He that idly loses five shillings worth of time loses five shillings, and might as prudently throw five shillings into the sea.”

In the 1940s I didn’t yet understand that idly throwing five shillings into the sea is far more prudent than haphazardly polluting it with fifty tons of toxic waste, but after four years at Yale College in the 1950s (the higher education geared to the production of alumni willing and able to fund the endowment), I was clear on the point that standard American time (Eastern, Central, Mountain, and Pacific) is its valuation as money, that the gospel according to Benjamin Franklin was the state religion, that the country’s social, political, and commercial enterprise was rooted in the belief that the worth of a thing is the price of a thing.

The commodification of time sets the terms of almost the whole of the American conversation, time in its current usages—overtime, downtime, spending time, saving time, killing time, buying time—nearly always a synonym for money. On the global currency market that circles the earth at the speed of light, $1 billion moves from here to there over the distance of less than a second, and Michael Lewis reports the selling of microseconds and milliseconds for hundreds of millions of dollars to stock-market traders looking to accelerate the arrival of the future. Mac McClelland describes the conditions imposed on workers sorting goods for shipment from warehouses like the ones operated by Amazon and Walmart—“A minute’s tardiness after the first week earns us half a penalty point, an hour’s tardiness is worth one point, and an absence one and a half; six is the number that equals ‘release.’ ”

Tardiness is next to wickedness in a society relentless in its consumption of time as both a good and a service—as tweet and Instagram, film clip and sound bite, as sporting event, investment opportunity, Tinder hookup, and interest rate—its value measured not by its texture or its substance but by the speed of its delivery, a distinction apparent to Andy Warhol when he supposedly said that any painting that takes longer than five minutes to make is a bad painting.

Only a small fraction of mankind’s time on earth (maybe 800 of the last 200,000 years) has been spent in the close company of mechanical clocks, remanded to the custody of a machine unrelated to anything other than itself. That the association has not proved to be a happy one is the conclusion drawn by Jay Griffiths from her researches among peoples native to the Andaman Islands, the Alaskan wilderness, the highlands of New Guinea and Peru, territories in which the local time is variously marked by the movement of toads and the fluttering of moths, by the scent of oranges and coconut, by “bear births, eagle marriages, and salmon deaths.”

As it is now at the margins of the twenty-first-century global economic imperium, so it was everywhere in antiquity, in Egypt and Mesopotamia as in Africa, India, and China, when time was understood by its human companions not as the measure of an abstract quantity but as a particular and concrete experience. Myriad sorts and kinds of time, all of them vividly alive in wind and leaf, bird and water, shifting with the change of mood or weather, marching to different drums in different directions, turning on the wheel of fortune that is the revolving of the sun and moon, flowing into the rivers Nile and Styx. Hesiod’s Works and Days, the preclassical Greek poem dating from around 700 bc, names the days of the month in accordance with their character (“Beware of all fifth days; they are harsh and angry”) or for their alignment with a human undertaking, some days good “for shearing sheep,” other days “to geld the boar and the bellowing bull.”

The pagan systems of keeping time didn’t serve the interests or the expectations of the Christian church. The Book of Ecclesiastes acknowledges multiple seasons of time (to plant and pluck up, to mourn and to dance), but at the end of his lesson the preacher reminds the faithful that time in all of its voices and declensions is the property of God, its treasures on earth to be placed in escrow guaranteeing on-time delivery and first-class accommodation in the theory of heaven.

The prefects of the new Christian world order rising in Western Europe from the ruin of the Roman Empire divided mankind’s time on earth between the years before the birth of Christ and the Anno Domini belonging to God. In the mid-sixth century, Saint Benedict arranged the hours of the day into a sequence of prayers decontaminating the flow of time within the walls of monasteries, time emptied of its doctrinal impurities and sexual intoxications.

The faithful elsewhere in Christendom observed holy days of obligation, among them the Solemnity of All Saints and the Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception, aligned not with the times of planting or plucking up but with the promise of their full value to be realized upon redemption after death by the sublime pawnbroker in the sky. The manufacture and sale of sacred time furnished the Catholic Church with its worldly wealth and sustained its political control of immoral nature made manifest in the sins of both the human spirit and its mortifying flesh. The first mechanical clocks to appear in Italy’s city squares in the thirteenth century were those mounted on church towers, not only to supervise the comings in and goings out of fallible humanity, but also to mark time’s blessed progress toward the triumph of its extinction.

The perfecting of mechanical clocks in Europe takes place over the five centuries encompassing the Italian Renaissance, the Protestant Reformation, the scientific and industrial revolutions, their bona fides and authority established by the seventeenth-century astronomer Johannes Kepler (“The celestial machine is to be likened not to a divine organism, but rather to a clockwork”), and by the seventeenth-century natural scientist Isaac Newton, who was also master of Britain’s royal mint (“Absolute, true, and mathematical time, of itself, and from its own nature, flows equably without relation to anything external”). French Jesuit missionaries bringing Christianity into the seventeenth-century North American wilderness taught the Huron to recognize the will of God in the face of “Captain Clock”; so in nineteenth-century Europe, while the universal and uniform time shifted from the biosphere to the technosphere, the Captain’s coercive omnipresence facilitated the transfer of political power from the landed aristocracy and the cloistered clergy to the bourgeois captains of industry and finance.

Money and time on the clock are both inanimate abstractions, nowhere to be found (as either animal, mineral, or vegetable) in the living body of time that is the existence of man and nature. The linking of time to power that was the essence of the Industrial Revolution is now the essence of the age of information; the self-destroying swindle that is the exchange rate between the worth of a thing and the price of a thing was calculated by the poet William Wordsworth in 1805:

The guides, the wardens of our faculties

And stewards of our labor, watchful men

And skillful in the usury of time,

Sages who in their prescience would control

All accidents, and to the very road

Which they have fashioned would confine us down

Like engines…

The skillful usury of time practiced by England’s nineteenth-century factory owners and venture capitalists brought forth industrial wastelands like the one pictured by Charles Dickens in 1854 in the novel Hard Times: “Every day was the same as yesterday and tomorrow, and every year the counterpart of the last and the next….Time went on in Coketown like its own machinery: so much material wrought up, so much fuel consumed, so many powers worn out, so much money made.”

The users of other people’s time, who change it into money of their own, found the voice of the annunciation in the person of

Frederick W. Taylor, gang boss in a Pennsylvania steel mill who in 1903 published Shop Management, a treatise declaring that “the natural laziness of men is serious, but by far the greatest evil” was the tendency of workmen to perform their task at a pace that “they think will promote their best interests,” an inclination equivalent to the idleness identified by Saint Benedict as “the enemy of the soul,” and one that clearly needed to be checked. To do so, armed with stopwatch and notebook, Taylor followed workers around factory floors in Pennsylvania, timing their every move, establishing the methodology that made him a best-selling wonder of the age, prompting the Encyclopedia Britannica to name him “the father of scientific management,” influencing the twentieth-century development of “virtually every country enjoying the benefits of modern industry.” Benefits accruing to time hardened into money, not to the perception and passage of time as experienced by people locked down on assembly lines or securely bound in the abstraction of unforgiving debt.

The historian Lewis Mumford names the clock, not the steam engine or the printing press, as “the key machine of the modern industrial age…a piece of power machinery whose ‘product’ is seconds and minutes: by its essential nature it dissociated time from human events,” and Taylor’s template for an efficient workplace appeared during the same few decades around the turn of the twentieth century that also vastly extended the powers of machine-made time to levy taxes, amass capital, declare war. The speeding up of time by telegraph and telephone, on radio and film, with fast-moving automobiles, airplanes, and artillery shells depended for its supremacy on Newton’s conception of absolute, true, mathematical time that of its own nature flows without relation to anything external—neither to the laws of gravity nor the nature of human beings.

The hypothesis was declared inoperative by Albert Einstein in 1905, then again with the publication in 1916 of the more readily understood Relativity: The Special and General Theory: “Every reference body (coordinate system) has its own particular time; unless we are told the reference body to which the statement of time refers, there is no meaning in a statement of the time of an event.”

Time carried back to the future, once again seen and understood as it was in antiquity, not only as mortal enemy but also as immortal ally. The counterrevolution against the autocratic regime of uniform, global time (commercially and politically imperialist) was pressed forward by many of the artists and writers of Einstein’s generation unwilling to bide time emptied of its being in order to accommodate the running of railroads and the rounding up of armies. In 1889 the French philosopher Henri Bergson discredits the measurable magnitude of time; Marcel Proust encapsulates the whole of a lifetime within a moment’s swallowing of a pastry; the cubist paintings of Picasso, Duchamp, and Braque play with the rearrangement of time in space, and the advent of Thomas Edison’s motion pictures in 1891 provide a means of printing time as a currency more durable than money. The Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky suggests that “what a person normally goes to the cinema for is time: for time lost or spent or not yet had,” time in the form of fact, “a way of reconstructing, of recreating life.”

La Petite Mort Film Still #1, by Alex Prager, 2012. © Alex Prager, courtesy of the artist.

Time moves more quickly and efficiently by wire than it does on horseback or on foot, but the faster it goes, the harder it is to know (or taste or smell or touch), an observation that William Faulkner, in his novel The Sound and the Fury, published in 1929, locates in the head of his Harvard undergraduate protagonist, who first breaks, and then refuses to repair, a watch—“Because Father said clocks slay time. He said time is dead as long as it is being clicked off by little wheels; only when the clock stops does time come to life.” Virginia Woolf’s novel The Waves, published in 1931, presents a petition protesting the tyranny of Captain Clock: “It is a mistake, this extreme precision, this orderly and military progress; a convenience, a lie. There is always deep below it, even when we arrive punctually at the appointed time with our white waistcoats and polite formalities, a rushing stream of broken dreams, nursery rhymes, street cries, half-finished sentences and sights—elm trees, willow trees, gardeners sweeping, women writing—that rise and sink.”

The pagan appreciations of time implicit in the writing of both Faulkner and Woolf (as well as in the novels of James Joyce and the dream interpretations of Sigmund Freud) correlate with Jay Griffiths discovering that the Maori in New Zealand envision themselves moving backward into the future as they face the past, a practice consistent with the thought of Søren Kierkegaard (life must be lived forward, but it can only be understood backward) as with the thirteenth-century reflections of the Zen Buddhist Dōgen. That the old ways of telling time maybe have come full circle is a truth told by the Lord Krishna in the Bhagavadgita around the year 100—“I am the self abiding in the heart of all creatures; / I am their beginning, their middle, and their end…I am the dice game of gamblers”—retold in 2005 by the British cosmologist Stephen Hawking: “So look well at the map of the microwave sky. It is the blueprint for all the structure in the universe…God really does play dice.”

If I read correctly Jim Holt’s essay “

The Grand Illusion,” the physicists and philosophers three quarters of a century after the birth of the atomic bomb confronting the problem posed by Aristotle three centuries before the birth of Christ have come no nearer to a clear and present solution than did the tutor of Alexander the Great. The consensus currently in vogue apparently holds that the separation between past, present, and future is probably an illusion, certainly a fiction, possibly a steady state in which everything that ever was or is yet to be is contained in a vast universe of eternity that swells but doesn’t move.

For my own part I need no length of measurement or metaphor to know that the past is up and doing in the present, born again in memory or dream at every hour of the day and night, awakening and reawakening itself in the compost heap of human thought that is the history of mankind’s traveling across the frontiers of the millennia.

This is Year Zero.

—Pol Pot, 1975Ryszard Kapuściński, assigned by a Polish newspaper to report on the civil wars in Africa, sits on the veranda of the Sea View Hotel in Dar es Salaam in 1963 reading the ancient Greek historian Herodotus and finds himself feeling “more deeply” about the destruction of Athens in the fifth century bc “than about the latest military coup in the Sudan,” the sinking of the Persian fleet at Salamis striking him “as more tragic than yet another mutiny of troops in Congo.” So also my own experience at the age of nine watching the American Navy depart for war in the Pacific while lying on the grass at the San Francisco Marina with a grammar-school edition of The Odyssey. Cognitively and emotionally I was more involved in what I was reading than in what I was seeing, the long-ago return to Ithaca of Homer’s wide-wandering hero seeming to me of greater pith and moment than General Douglas MacArthur’s much-heralded return to the Philippines in October 1944.

The Roman playwright and statesman Seneca, tutor to Emperor Nero, speaks of reading what to him in the first century was the ancient philosophy of Socrates and Epicurus as the entering “into a partnership with every age,” allowing him to add to his own lifetime “the presence of things,” brought by others “from darkness into light.”

When I was a child, I thought the pageant of the past was still intact and traveling in space at 186,282 miles per second, aboard a science-fiction beam of light under the command of Captain Clock. Not yet having learned how to count time as money, I know the beam of light is time shaped by the force of the human imagination and the powers of its expression (in the languages of art and science but not as the commodity discounted as an abstraction), and I’m content to live temporarily suspended in as many kinds and sorts of time (historical, biological, metaphysical, and mythological) as were my pagan forebears long since descended into the glossy darkness under the turf at Stonehenge.