The whole secret of fencing consists but in two things, to give and not to receive.

—Molière, 1670The Comeback Kid

The marvelous and true tale of Alex Rodriguez seemed an unlikely prospect for the role of the Comeback Kid.

By Terry McDonell

Alex Rodriguez hitting his twenty-fifth home run. Mike Liu, Shutterstock.

Among the greatest sports stories ever told, none pulls more sweetly at the heartstrings than the one about the Comeback Kid. The fall from grace followed by the rise to glory. The hero down in the count or left in the dust, making the come-from-behind move at the clubhouse turn, floating it out of the park with two out in the bottom of the ninth. The fan nation wonders where Joe DiMaggio has gone and looks to its greatest athletes to preserve its hope, and time was when they could provide the stuff of dreams and supply sportswriters with grist for the mills of legend.

The sweet story no longer holds true to form. The invincible Tiger Woods takes a leave from golf after multiple infidelities are revealed by at least nine mistresses. He says he is sorry. It’s hard to believe him. He returns to competition without his game, another middle-of-the-pack golfer. Michael Vick, the most exciting player in the NFL in 2006, goes to prison for dogfighting, returns to football without his game, and barely gets off the bench. Pete Rose, the banished “Hit King,” never to be forgiven for betting on baseball, hustles his own autographs in Las Vegas.

Sportswriters know too much to save them from disgrace in Mudville, and so the task falls to the flacks and publicists, the stylists, image consultants, and crisis managers who have become our newfound instruments of redemption.

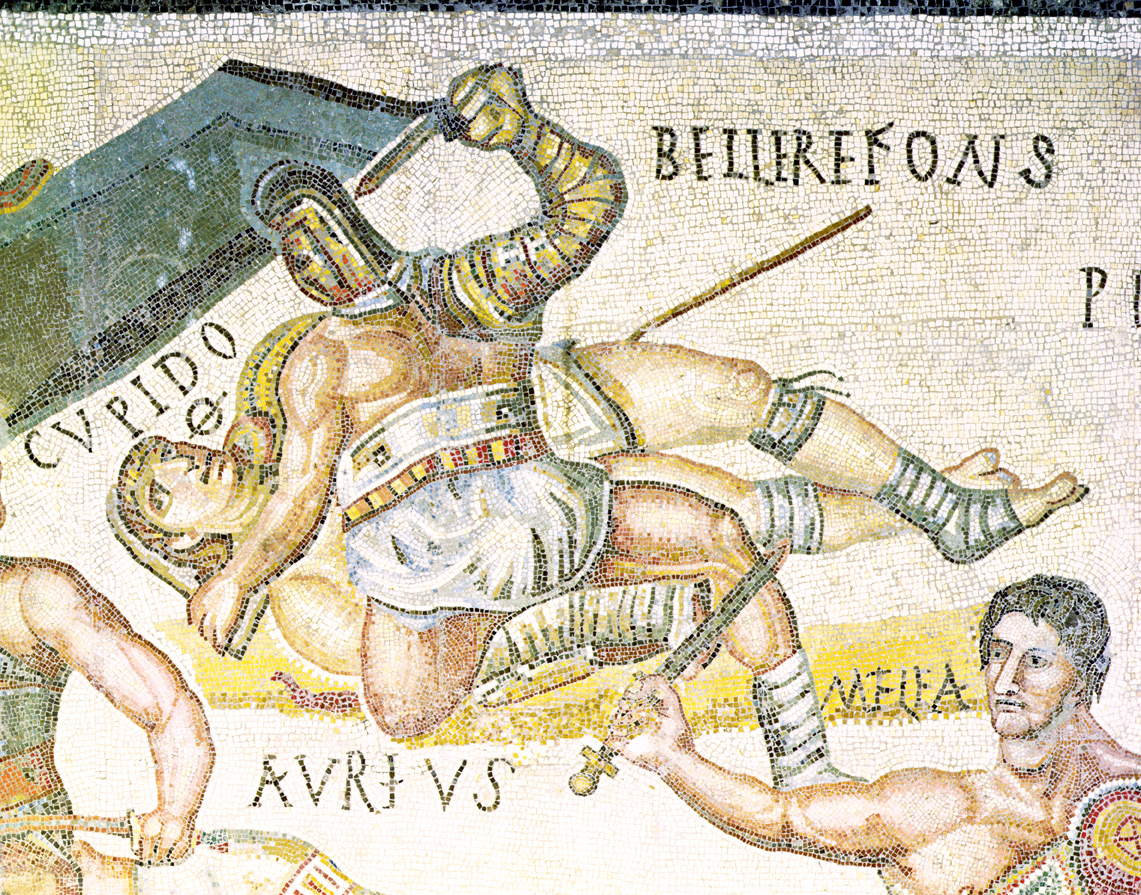

Match between gladiators, Roman mosaic, c. 325. © Galleria Borghese, Rome. Alinari, The Bridgeman Art Library International.

Take the marvelous and true tale of Alex Rodriguez, an unlikely prospect for the role of the Comeback Kid. “A-Rod” is tabloid shorthand now, having been linked to Madonna, having slapped the ball out of Bronson Arroyo’s glove during the 2004 American League Championship Series, having apologized on national television for being a liar and a cheat. But the nickname was always part of a marketing plan, trademarked back in 1996 as a branding tool under the umbrella of A-Rod Corp, LLC. And A-Rod has always liked being called A-Rod. Let’s call him Alex.

Alex was born July 27, 1975, to Dominican parents in New York City, where he currently plays third base for the Yankees. He is considered one of the best all-around baseball players of all time, his $275 million contract the richest in baseball history. Alex’s five-hundredth homer cleared the left-field wall in Yankee Stadium just past his thirty-second birthday, putting him on track to claim the lifetime home-run record that Barry Bonds was closing in on at the time. Bonds, of course, was spreading asterisks over the sediment layers of statistics on which the game rests in his steroid-fueled odyssey to surpass the 755-homer mark set by the great Henry Aaron. Alex was different, still young and seemingly almost innocent enough to bring smiles to cynical fans disillusioned by reports that Bonds’ hat size had ballooned from 7⅛ to 7½ and that aging Yankees fireballer Roger Clemens was injecting illicit substances into his buttocks.

But then, on February 9, 2009, after previously denying use of performance-enhancing drugs—including during an interview with Katie Couric on 60 Minutes, in which he said he was such a natural he didn’t need any enhancement—Rodriguez shockingly admitted to taking steroids. His voice clutching, Alex said he used them from 2001 to 2003 (the year he was American League MVP) due to what he called “an enormous amount of pressure” to perform. It all made Alex very sad and angry and confused, and he hadn’t wanted to admit to anything. There is Providence in the fall of Alex. Just as long as Providence gives the slugger another shot.

I became the editor of Sports Illustrated in 2002, the year Ken Caminiti admitted to the magazine that he had used steroids during his National League MVP–winning 1996 season and for several seasons afterward. That was a big story, but Alex as a drug cheat was bigger because he was in midcareer. And, of course, because Alex was Alex. When Sports Illustrated senior writer Selena Roberts confronted him in his Miami gym, he couldn’t believe what was happening. That the magazine had proof of his positive test for Primobolan and testosterone was about to break in the February 16 issue. He refused to talk to Roberts and almost immediately flew to the Bahamas, presumably to consider his options. He knew the Sports Illustrated report was true and that, unfortunately, he would probably have to acknowledge it. Alex wound up in the VIP area of the Aura Nightclub at the Atlantis Resort, where he was tagged by paparazzi hugging a brunette on his lap with “a blond on deck,” according to the caption in the New York Post. Alex was letting his own story get away from him. What was Alex was thinking, what kind of advice he was getting?

It turned out Alex had been getting a lot of advice, and not just from his trusty posse of cousins, trainers, and old buds on pressing matters such as, say, breakfast drinks, real estate, and bringing the car around. The most visible was Alex’s famously cold-blooded agent, Scott Boras, with his more than forty-five employees in Newport Beach, California. Alex’s manager was Guy Oseary, who also managed Madonna and had engineered Alex’s signing with the William Morris Agency to extend his brand beyond baseball, and brokered the Katie Couric 60 Minutes piece. Alex’s lawyers were Jay Reisinger and James E. Sharp, who advised steroid slugger Sammy Sosa when he testified before Congress. And then suddenly, with the news about to break, there was the consulting firm Outside Eyes (also based in Newport Beach), which specializes in “media strategy, brand development, and crisis management.”

Outside Eyes was founded in 2005 by Reed Dickens, who worked on the 2004 Bush-Cheney campaign and went on to the White House as assistant press secretary. His partner Ben Porritt was the national spokesperson for the McCain-Palin campaign after doing battle as press secretary for Texas congressman Tom DeLay, when the then House majority leader was indicted on criminal charges of conspiring to violate campaign finance laws. According to their company website, Outside Eyes maintains a “War Room” for monitoring news and formulating rapid responses.

So what was the plan? It was clear that Alex was going to have to make a statement, come clean, in order to move on and rise up. Baseball fans were shocked, outraged. Alex was going to have to be very, very sorry. His advisers decided to offer him up exclusively to ESPN’s Peter Gammons. Great idea. But then it didn’t go all that well, because Alex didn’t seem to know anything except that when he was with the Rangers, he had been dumb and young and it had been a different time. And then, answering a question about being tested during the World Baseball Classic in 2006, Alex wandered into an angry non sequitur. “What makes me upset is that Sports Illustrated pays this lady, Selena Roberts, to stalk me. This lady has been thrown out of my apartment in New York City. This lady has five days ago just been thrown out of the University of Miami [by] police for trespassing. And four days ago she tried to break into my house, where my girls are up there sleeping, and got cited by the Miami Beach police.” One hell of a story.

None of this was true, but Gammons, the classy Hall of Fame baseball writer, suddenly started playing softball and followed up by asking, “How do you go about making people believe you?”

We at Sports Illustrated complained immediately to ESPN and issued a statement saying that Alex’s attack on Roberts was absurd. Various editors spent time on the phone with Ben Porritt of Outside Eyes; we assumed he would be up for it because of his experience explaining such questions as what Sarah Palin meant when she said the First Amendment should protect her from reporters. Porritt was smooth, professional, and vaguely ironic. Sports Illustrated wanted an apology for our reporter Roberts. Right. Good one.

But lo and behold, two days later Alex called Selena Roberts. Helping him was Porritt. “You’re on speakerphone,” Porritt announced, when he reached Roberts on her cell. “I’m here with Alex.”

Boys Playing at Seesaw, attributed to Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes, c. 1785. National Museum, Gdańsk, Poland.

It had been a bad week for Alex, but he had been getting some serious coaching, and the idea was to massage the situation and spin an apology that told the story the way he wanted it: he was going to become the Comeback Kid. Porritt insisted to Roberts that the call was off the record; Alex was not going to correct the record publicly, even after acknowledging privately that his allegations against her were false, and therefore he was not going to repair the damage to Roberts’ integrity—her most valuable asset as a journalist. But Alex could now say he had said he was sorry. Which he did when he finally met the press again at Yankees spring training in Florida. He also apologized for being “a lot nervous” before ending his prepared statement with this: “It isn’t lost on me the good fortune I’ve received from playing baseball. When I entered the pros, I was a young kid in the major leagues. I was eighteen years old, right out of high school. I thought I knew everything, and I clearly didn’t. Like everyone else, I’ve made a lot of mistakes in my life. The only way I know how to handle them is to learn from them and move forward. One thing I know is for sure that baseball is a lot bigger than Alex Rodriguez.” Well done, Alex.

Supported by Yankees teammates on folding chairs in a special section of the briefing room, Alex answered one question about what he called “a misunderstanding” with Roberts and emphasized that all he wanted to do was get back to hitting home runs. He was his story now. He was calm, almost smiling, his sense of entitlement and privilege naked, the message clear. The more talent you have, the more you can get away with. Anyone who ever played big-time sports knows that—Tiger Woods now perhaps better than anyone. Alex almost winked at the camera.

Alex also implied he planned to become a spokesperson for the Taylor Hooton Foundation, which educates young people about the dangers of steroid use. He was on his way back. And think about it, he hadn’t really done anything illegal. His sponsors understood: he was still good for baseball. It didn’t even matter that some people called him A-Fraud or that, in one of those telling accidents of celebrity career planning, the April issue of Details with Alex on the cover featured a series of provocative poses of him in Calvin Klein tank tops—including a full-page image of Alex kissing himself in a full-length mirror.

Brand-new Alex, after a two-month recovery from hip surgery, opened his 2009 season with a home run against the Orioles in Baltimore. The crowd loved it, so did his teammates. “It was awesome,” Alex said. “I feel like I’m back with my family.” Alex was feeling good. Beyond his performance on the field, his divorce, the reporting of which in what Porritt might call the “gotcha media” had cast Alex in the role of serial adulterer “brainwashed” by Madonna, was final, over. Alex’s ex-wife Cynthia had asked for half of everything plus alimony to maintain their “high standard of living” for herself and their daughters Natasha, three, and Ella, three months. At first Alex wanted to stick to their prenup and said if Cynthia challenged it, he would make her pay his legal fees when she lost. In the end their lawyers had worked something out, and Alex’s love life was only getting better. His relationship with Kate Hudson was public now, and he liked the attention—or perhaps simply the recycling of gossip that he was getting used to. This was much more fun than being linked to women in common with former New York governor Eliot Spitzer, which was embarrassing. But that wasn’t going to stick; everyone knows politics and sports are worlds apart. The Yankees went on to win the 2009 World Series, with Alex Rodriguez going 19 for 52 (.365), with six homers and eighteen RBIs in the postseason.

By the beginning of the 2010 season, Alex was living in a $30,000-a-month rental apartment on Central Park West and had moved on from Kate Hudson to Cameron Diaz. Up and up. On the field he looked bloated but was on track to hit his six-hundredth home run well before September, which would keep him on track to break Barry Bonds’ record. He posed for the April/May cover of Gotham magazine, and the slick but fundamentally cheesy glossy explained how Alex got his “cover look” by superimposing bottles, tubes, and jars of cosmetics over his image. “Facial Fuel Healthy Bronze ($22.50).”

The story of Alex’s comeback was not a tale told by an idiot signifying nothing. The work was done by high-paid professionals, free agents dealing in the commodities of sound and fury. Alex telling his own story to a mirror.