The battlefield of Peach Tree Creek, Georgia, 1860s. Photograph by George N. Barnard. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Pfeiffer and Rogers Funds, 1970.

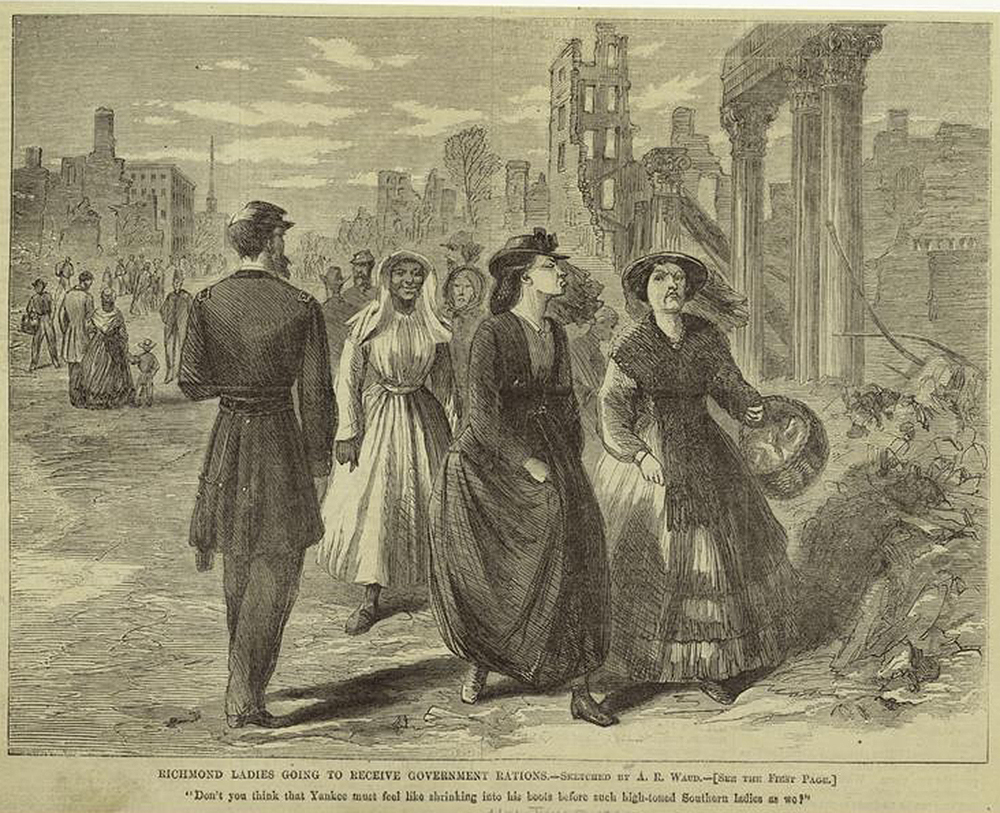

The ends of wars, when they come, are always dangerous moments, ripe with possibilities of every sort. Peace must be made, armies dismantled, enemies held accountable, refugees returned, cities rebuilt, nations and individual lives reconstructed from the ruins. Everywhere after wars, women live those histories in ways particular to their sex.

In the American South in the spring of 1865, as so often happens in the aftermath of wars, the conquered and the liberated lived through the process of reconstruction in awful proximity. Far from the centers of global or national power, on a plantation six miles outside of Augusta, Georgia, one woman, Ella Gertrude Clanton Thomas, lived through it all: destruction, defeat, occupation, emancipation, political uncertainty, and, as would become clear, a long, grinding descent into poverty. Thomas kept a forty-one-year record of her life that captured the historical passage. She knew she lived in radical times: “The fact is,” she wrote shortly after surrender, “our Negroes are to be made free and a change, a very [great] change will be affected in our mode of living.” Indeed.

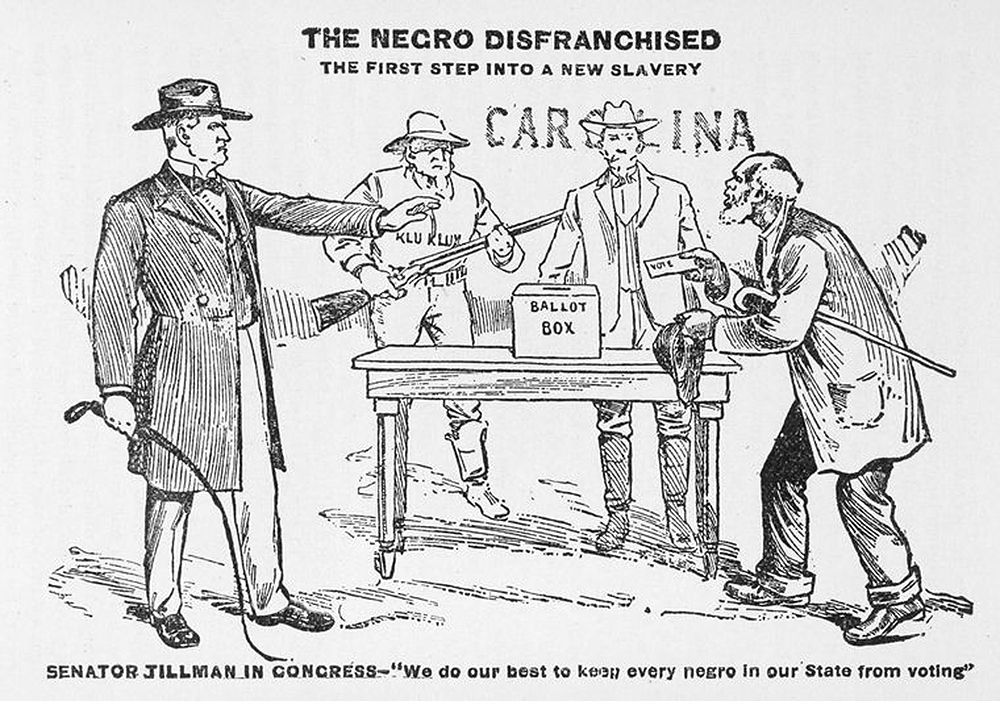

By the time of the presidential elections in 1868, freed people had already won significant victories in two elections that made Republicans’ political strength in Georgia demonstrably clear. The party had racked up big majorities in both cases, defeating white Democrats decisively and then using their power in the state convention to write and ratify a radical constitution and install a Republican governor and legislature that included the state’s first elected black representatives. Black male voters had demonstrated their power decisively. As a majority within the state and voting solidly Republican, they would not easily be dislodged by electoral means. After the April 1868 elections, the new (white) Republican mayor of Augusta, Foster Blodgett, tried to contain a white backlash that seamlessly intimidated blacks as both laborers and voters. “Many colored people in this and adjoining counties have been discharged by their employers for voting the Republican ticket at the last election,” he wrote, “and in some instances, women have been discharged because of their husbands’ vote.” Appealing to the military, he begged to know what could be done “for their protection.” White Democrats responded to radical Reconstruction with a campaign of violence so extensive that its leading historian, Allen W. Trelease, bluntly refers to it as “terrorism.” Violence against African Americans, including by white men who disguised their identities, had started in 1865, as Freedmen’s Bureau records confirm. But the pattern of violence escalated steeply with the onset of black electoral politics and radical Republican rule. By 1867, it constituted a highly organized campaign of arson, torture, mutilation, sexual violence, and murder. Indeed, the Ku Klux Klan, as the movement became known, was so organized and lethal that it still constitutes the primary example of domestic terrorism in the history of the United States. Trelease offers the informed judgment that the Klan’s role in the overthrow of Republican control was greater and more decisive in Georgia than in any other part of the South. Within the state, the campaign of terror against Republicans, and especially black Republicans, reached its vicious “apotheosis” precisely where Gertrude and her husband Jefferson Thomas lived—in the black-majority districts in the eastern part of the state, including Richmond and Columbia Counties.

That campaign of political violence not only reached, but also radiated out from, Gertrude and Jefferson Thomas’ home plantation.

As Election Day approached and white Democrats prepared themselves for a pitched battle, “radicals” at Belmont, led by two men, Isaiah and Mac, were organizing on the plantation in preparation for voting the Republican ticket. They had plans to “meet at the creek tomorrow night,” Gertrude was informed, “to march to town the next day with Uncle Isaiah as captain.” “Things are rapidly approaching a crisis,” she noted two days before the election. “It is reported that all of the houses in the neighborhood are to be burnt up.” Her informant among the Belmont freed people, a teenager named Ned, told her that “Uncle Mac said if he had a son who was willing to be a Democrat he would cut his throat.”

Arrayed against each other, and amid rumors of violence and arson, white and black at Belmont prepared for the coming fight. The night before the election, Jefferson Thomas went out to patrol with the local militia company, “of which he is captain,” his wife noted proudly. Before he kissed her goodbye, he asked to have his guns brought up. There they sat, stacked in the corner of the kitchen. When her husband left, Gertrude expressed her hope that that there would be “no necessity for force…Only absolute necessity [would cause] Southern men to resort to force,” she noted that night. It was a claim refuted by a long history.

On Election Day, everyone girded for violence. “No wonder the great heart of the South throbs at the thought of how much will depend upon the vote of today,” Gertrude noted nervously that morning. “Mr. Thomas went to Pine Hill to vote,” she added. “Mr T.” would have a leading role to play, as she knew: he was “captain of the [militia] company in Augusta,” and in this neighborhood “president of the Democratic club.” It was a damning admission, as Virginia Burr, the editor of Thomas’ diary, was quite aware. Burr omitted that entry entirely from the published diary, as she did earlier references to Jefferson Thomas’ role as captain of the militia during the violent campaign of voter suppression and a later one to Gertrude’s brother Buddy, known by local black Republicans as “one of the Ku Klux.” The published diary has been scrubbed clean. Those critical entries lie buried among more than two thousand manuscript pages in the Rubenstein Library at Duke University.

But it is impossible to inoculate Gertrude Thomas from her family history. And it is impossible to inoculate family history from political history: the existential political battle of Reconstruction unfolded not just in public places and institutions but within the households and homes of Southern planters and laborers. The Klan was effectively “a terrorist arm of the Democratic party,” and it had been built up and organized around a network of “Democratic clubs” and rifle clubs such as the one Jefferson Thomas led. They had been formed after Republican victories in the April 1868 elections and were extremely active around Augusta, targeting black voters before the November elections. “Virtually every night prior to the election the Klan rode out in parts of Richmond, Warren, Columbia, Lincoln, and Greene Counties,” Trelease explains, “searching for guns among the freedmen, whipping and threatening death to any who voted Republican.”

Klan members wanted a violent overthrow of the state government and an abrogation of electoral democracy in the presidential contest. Jefferson Thomas played a leading part in his precinct as captain of the militia company and president of the Democratic club. In 1868, white militias, Democratic clubs, and the Klan were instrumental in Republican electoral defeat in Georgia. In Columbia County, the Republican candidate for governor, Rufus Bullock, garnered 1,222 votes in the April elections; in November, Republican presidential candidate General Ulysses S. Grant got exactly one. On Election Day companies of armed whites, with Jefferson Thomas commanding at Pine Hill, assembled around the polls, confiscating Republican ballots and intimidating voters. Black voters had to run the gauntlet just to get to the poll. “In Columbia County,” Trelease confirms, “they even intimidated the soldiers who had been sent there” as poll watchers. Notwithstanding the efforts of sharecroppers such as Isaiah and Mac, who marched to the polls en masse and armed, Republicans around Augusta could not match the firepower of men such as Jefferson Thomas.

In Augusta, there was violence on Election Day, a riot with “the white men” (as Gertrude put it) lined up on one side facing down the black men who were attempting to come to town to vote. “Yankee” soldiers, fittingly, were in the middle. The deputy sheriff was shot. Mac, the sharecropper at Belmont, came back and proudly reported that he had voted the Republican ticket. When he was asked to name the candidate he had voted for, Gertrude claimed he turned to her son Turner and asked whom he had voted for. Hearing the answer, Mac said, “Then I voted for the other side.”

By that point any fiction of mutual interest was gone. We trusted ourselves to “the coloured people” earlier “during the war,” Gertrude Thomas wondered. “Why not now?” But the answer was clear: because black laborers were now free to express their views of the relationship, opinions that had been violently silenced under slavery. Freed people were no longer required to maintain the pose of devoted family servants. They had staked out their own position in the conflict between capital and labor. And they had given political force to their interests as newly freed African Americans and enfranchised male citizens through the Republican Party.

Relationships Gertrude Thomas had always regarded as internal to the household, as personal bonds of attachment—hierarchical but mutual—were nakedly exposed as public economic relations—antagonistic and defined by power. These relations were now compensated with a wage and regulated by the market. Emancipation made visible the violence that had always characterized the relationship of master and slave, turning social and political life into an armed struggle. As Thomas’ perspective on the election of 1868 confirms, political violence was as much a household as a public affair. Thomas would continue to denounce federal interference in Southerners’ “domestic affairs,” but really, there was nothing domestic about them anymore.

Gertrude Thomas’ sense of personal loss as she fiercely clung to white power and privilege cannot be disentangled from her husband’s violent contribution to the so-called redemption of the state from “black” Republican rule. They were all manifestations of the desperation to forge a new kind of white supremacy equal to the new terms of social and political life. Gertrude Thomas shared—though not entirely—her husband’s racist perspective on the political revolution of Reconstruction. The one difference was that she understood why “the Negroes vote the radical ticket” because, disfranchised herself as they were formerly, she knew the value of the vote:

Think of it, the right to vote, that right which they have seen their old masters exercise with so much pride and their young masters look forward to with so much pleasure is within their very grasp—they secure a right for themselves, which it is true they may not understand, but they have children whom they expect to educate. Shall they secure this right for them or sell their right away?…Who can guarantee that right will ever have it extended to them again.

From her perspective as a woman denied political rights, Gertrude Thomas could see the issue from the other side. “If the women of the North once secured to me the right to vote whilst it might be ‘an honor thrust upon me,’ I should think twice before I voted to have it taken from me,” she declared. And by this point Gertrude Thomas had good reason to think about the value of self-representation.

For Gertrude Thomas Reconstruction proved much harder to survive than war. For her, Reconstruction was more like deconstruction—a relentless process of loss, subtraction, and diminution in wealth and class distinction. The year 1868 was the turning point, the moment when she was first “brought to bankruptcy” and began to grasp the extent of her husband’s financial troubles. The following year, the Thomases went under the sheriff’s hammer for the first time—and the dunning did not stop until they had lost everything. Their personal history paralleled that of the region and reveals its new political powerlessness within the national and global financial order. Gertrude knew times were hard for all cotton planters, but she also knew that many managed better than her husband. Jefferson Thomas was pursuing the usual course of action for the planter class, but there was something different about their condition. “In my own conscience, I think a great deal of what we call bad luck is bad management,” she noted bluntly. In the midst of their financial crisis, she observed that “this is infinitely worse than Sherman.” Then “it was so general a loss that we could sympathize with each other but this trial I am undergoing now is lonely.”

Excerpt adapted from Women’s War: Fighting and Surviving the American Civil War by Stephanie McCurry, published by Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2019 by Stephanie McCurry.