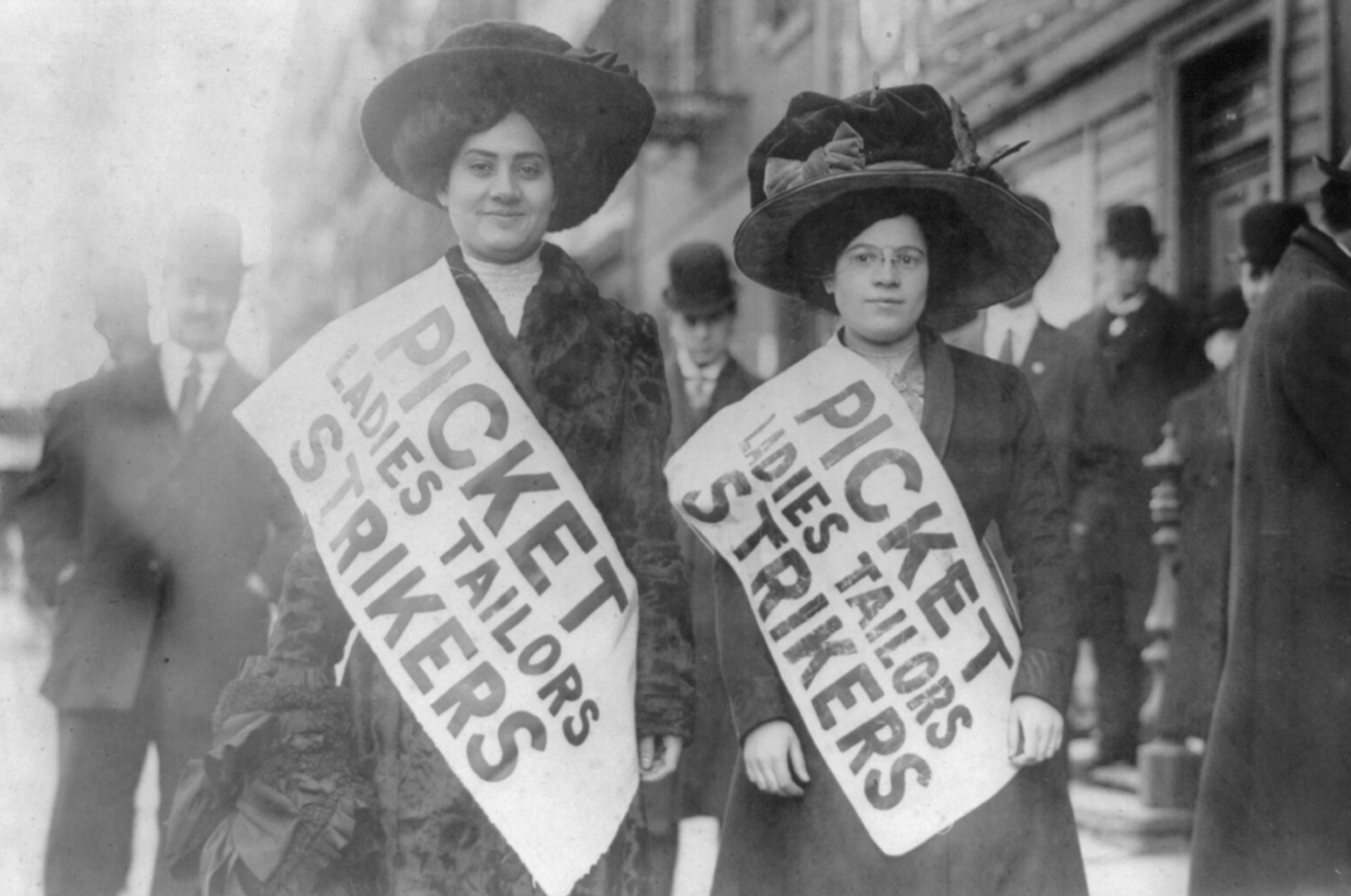

Two strikers during the Uprising of the Twenty Thousand, 1910. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, George Grantham Bain Collection.

On March 25, 1911, a fire broke out at the Triangle Shirtwaist Company factory off Washington Square in Greenwich Village. The employers had locked the doors and blocked the emergency exits, supposedly to keep the workforce from leaving early, but now they were trapped. Because of that callous decision, 146 workers (primarily young women, but also including twenty-three men) lost their lives, many having jumped from the upper floors to escape the flames. Two years earlier, the labor organizer Rose Schneiderman had led many of those same workers on strike as part of the Uprising of the Twenty Thousand that swept through the sweatshops on the Lower East Side. The strikers won many of their demands, but the Triangle Shirtwaist Company was one of the shops that held out. If its owners had agreed to the strikers’ demands for a half day on Saturday, there would have been no workers inside when the fire broke out that fateful afternoon.

Rose Schneiderman lost several friends in the conflagration, but she hardly needed a personal connection to fuel her outrage. At a mass meeting the wealthy socialite Anne Morgan organized to demand stronger laws protecting the health and safety of New York garment workers, Schneiderman’s response was impassioned. Only ninety pounds and four and a half feet tall, with fiery red hair and the rhetoric to match, Scheiderman quickly shushed the restive audience at the Metropolitan Opera House. “I would be a traitor to these poor burned bodies if I came here to talk good fellowship,” she told the huge crowd. “This is not the first time girls have been burned alive in the city. Every week I must learn of the untimely death of one of my sister workers. Every year thousands of us are maimed. The life of men and women is so cheap and property is so sacred. There are so many of us for one job it matters little if 143 of us burned to death.” Then she drew this powerful conclusion: “I can’t talk fellowship to you who are gathered here. Too much blood has been spilled. I know from my own experience it is up to the working people to save themselves. The only way they can save themselves is by a strong working-class movement.”

Too often the images of the suffrage movement are of elite, white, native-born women, but that is an incomplete view. Working-class women played active and vibrant roles in the movement, especially in its last decade. These suffragists, coming out of the trade union movement and committed to organizing women into unions alongside men, were street-smart and politically savvy. They helped to revitalize the suffrage movement in its final years, and they contributed a broader theoretical perspective by arguing that class solidarity must always be prominent alongside gender.

Rose Schneiderman had traveled a long way to get to the stage of the Metropolitan Opera House. She was born to an Orthodox Jewish family in the small village of Saven, in Russian Poland, in 1882. Her father was a tailor and her mother was a skilled seamstress, who made sure that her oldest daughter had access both to public education and traditional Hebrew schooling. In 1890, the family migrated to New York City, settling on the Lower East Side. Although it was only a few miles from the Schneiderman’s tenement to the uptown enclave of successfully assimilated Jews like Maud Nathan and Annie Nathan Meyer, they lived in separate worlds. Two years after the family immigrated, her father died, leaving her mother pregnant with their fourth child. She tried to support the family by taking in boarders and doing piecework sewing, but for a time the three older children lived at a Jewish orphanage. When the family reunited, Mrs. Schneiderman went back to work, and young Rose took over running the household.

Rose first entered the paid labor force at the age of thirteen, working as much as seventy hours as a department store cash girl for the paltry wage of just two dollars a week. When she turned sixteen, she switched to industrial work, which was lower status but paid somewhat higher wages. Settling into the cap-making industry, she discovered not only the camaraderie of the shop floor but also the exploitation that workers, especially working women, faced at the hands of their male employers. In 1903, she and two other women organized the first female local of the Hat and Cap Maker’s Union. Two years later, she emerged as a leader during a successful thirteen-week strike in which the workers resisted employers’ attempts to introduce an open shop (that is, a nonunion factory). For the rest of her life, she was involved in broader questions of trade unionism and working women, primarily through the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) and the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL).

The WTUL, founded in 1903, brought together working-class activists and middle- and upper-class reformers in a single organization devoted to unionizing working women and securing labor legislation to improve their lives both on and off the job. Margaret Dreier Robins, the president of the New York branch, recruited Schneiderman to the organization in 1905. She was dubious at first, fearing she would just be a token, but Robins convinced her that this was a unique opportunity to participate in a true cross-class coalition. By then, Schneiderman had grown weary of male union leaders’ total lack of interest in organizing women in the trades. Hoping that this new organization offered a different way to work for social change, she threw her lot in with the women reformers, an association she maintained for the rest of her professional life. Being a young, working-class woman in an organization where she was expected to interact with older, middle- and upper-class allies was challenging. For one thing, unlike elite women who could volunteer their time, Schneiderman needed a salary to live on. The NYWTUL put her on the payroll, her salary made possible by contributions from wealthy women; no doubt there were times she had to tone down her outspoken socialism in order not to offend her wealthy benefactors. Other working-class activists got caught in this trap as well. This divide between the majority of reformers, who could contribute their time and energy to the cause, and the minority that needed to earn a living often complicated the union’s internal organizational dynamics. As a general rule, the leadership of the woman suffrage movement was almost exclusively in the hands of those who could afford to forgo a salary.

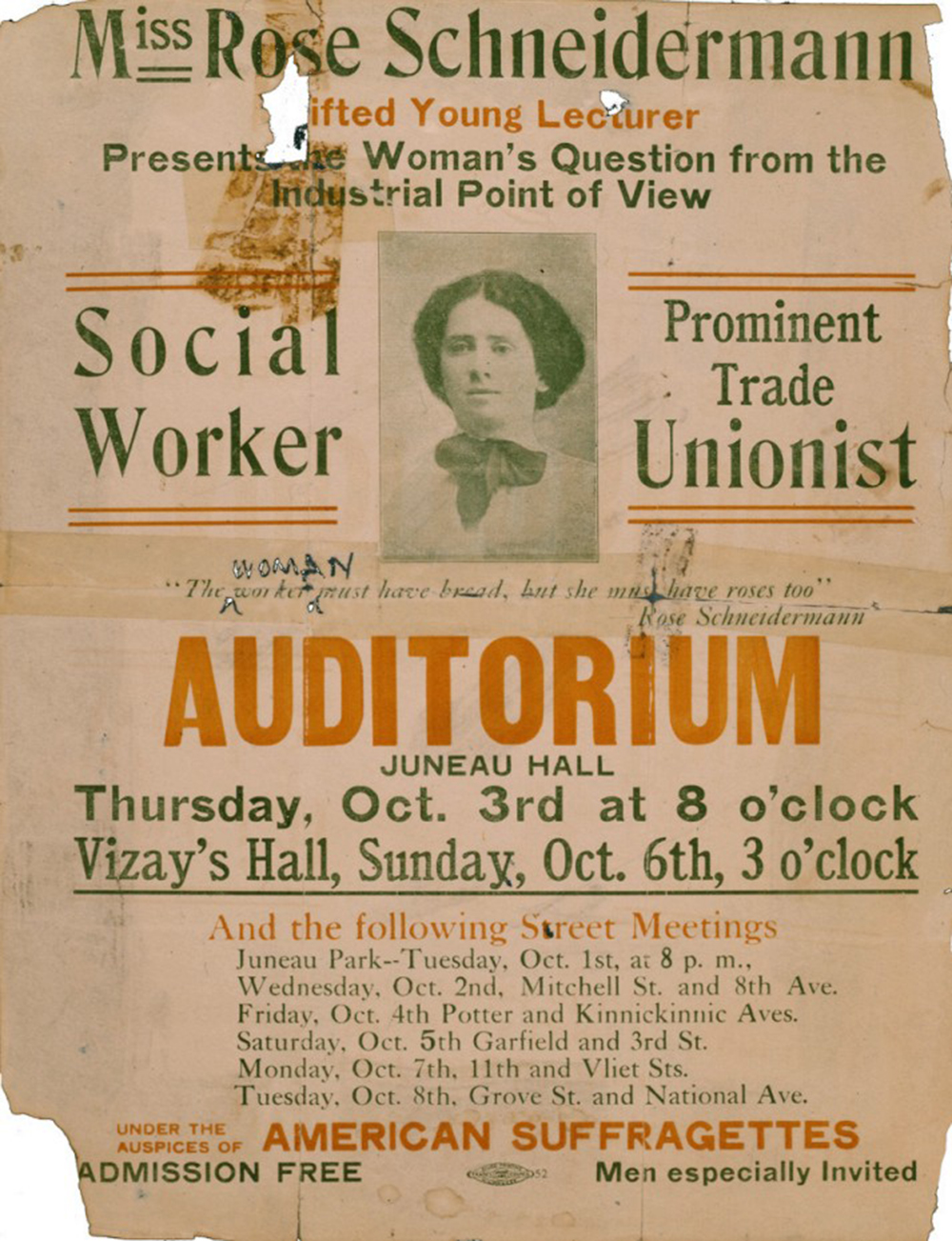

Schneiderman’s suffrage activism began in 1907, when she joined the newly established Equality League of Self-Supporting Women. She made her first public speech for suffrage at an April 1907 meeting at Cooper Union and quickly became the Equality League’s most popular speaker. She was especially at home as an impromptu street speaker, drawing directly on her years of union organizing to spontaneously attract a crowd when a factory let out for the day or wherever strollers congregated in public parks and squares. Besides being a good way to reach working people, these impromptu meetings were basically free, and certainly much cheaper than hiring a hall and distributing fliers.

The new reformer began to make a name for herself during the 1909–10 garment workers’ strike in New York. As the historian Annelise Orleck has argued, the Uprising of the Twenty Thousand represented “a moment of crystallization, the sign of a new integrated class and gender consciousness among U.S. working women.” By 1919, half of all women garment workers in the country belonged to labor unions. The strike was notable for the cross-class alliances it supported, with wealthy women—the so-called Mink Brigade of Alva Belmont, Anne Morgan, and others—marching on picket lines and raising money for bail and strike support, a harbinger of the roles wealthy women would play in the final stages of suffrage.

Schneiderman’s strong sense of class solidarity undergirded much of her suffrage advocacy. As a self-supporting working woman, she was able to point out how far women’s lives had already strayed from the domestic sphere. For example, she often poked fun at the idea that voting would somehow “unsex” women, especially in comparison to the rigors of industrial work. “Surely…women won’t lose any more of their beauty and charm by putting a ballot in a ballot box once a year than they are likely to lose standing in foundries or laundries all year round.” Or as she said on another occasion, “What does all this talk about becoming mannish signify? I wonder if it will add to my height when I get the vote. I might work for it harder if it did.”

In October 1915, New York was gearing up for a massive suffrage referendum. By now, Schneiderman was channeling her suffrage work through the Industrial Section of the New York Woman Suffrage Party. Vast resources of money and energy poured into this 1915 campaign, and hopes were high. But once again, the referendum went down to defeat, a discouraging turn of events for New York suffragists. At this point, a consensus was emerging that passing a national constitutional amendment to enfranchise women in one fell swoop was likely to be quicker than the state-by-state approach. A victory in a state like New York, with its large congressional delegation and forty-five electoral votes, could play a significant role in the amendment’s chances of passage in Congress. So New York suffragists decided to try again with a second referendum in 1917.

Schneiderman had spent most of the prior two years organizing for the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union, but in 1917, she was back in the suffrage fold for this one last battle. This time, the New York suffragists prevailed.

Rose Schneiderman’s suffrage story differs from other suffrage stories, and not simply because of class, although that is a major factor. Rather than a single thread or story line, her suffrage activism was part of a broad palette of social justice issues, mainly driven by her concern for empowering working-class women.

She never had any illusions that suffrage would be a solution or panacea to their problems, but she was convinced that the vote would be an important tool to confront the class and gender discrimination that belied the American dream of freedom and equality for all. Since so much organizational energy and momentum was gravitating toward woman suffrage, Schneiderman deliberately allied herself with this progressive movement, but because of her class consciousness, her vision was always broader than just the vote—something that was not true for all suffragists, many of whom saw the vote solely through the lens of gender. Like African American suffragists, Schneiderman anticipated the modern intersectional approach which posits that oppressions cannot be singled out or ranked, because they operate in tandem with each other. She knew from her own experience that class could not be separated from gender, and that awareness informed her entire political career.

The “race” leg of the intersectional triangle was less well-developed, even though she proved quite forward-looking in trying to organize African American laundry workers in the 1920s, a time when the labor movement totally ignored them. In the early twentieth century, however, especially on the Lower East Side of New York, where most of the working-class suffragists lived and worked, their world was predominantly white. The factories were white, the neighborhoods were white, and the suffrage organizations were white. That was the world that Schneiderman inhabited, for better or worse.

Rose Schneiderman once said, “The woman worker needs bread, but she needs roses, too.” Bread stood for basic human rights, such as decent wages and hours, safe working conditions, and respect for labor. Roses meant friendship, education, leisure, and recreation—what she called “the spiritual side of a great cause that created fellowship.” In Schneiderman’s view, working women deserved both. In 1916, twenty-six years after her family arrived on Ellis Island, she took out citizenship papers in anticipation of women’s enfranchisement.

Excerpt adapted from Why They Marched: Untold Stories of the Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote by Susan Ware, published by Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2019 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College.