Niagara Falls mills district, c. 1900. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

William T. Love hoped to give his name to history as an epic city builder and energy titan. Hailing from parts unknown (perhaps Knoxville or Chicago), Love arrived at Niagara Falls in the early 1890s. Though he occasionally sounded like a starry-eyed naturalist, Love was equally entranced by the region’s industrial possibility. He saw Niagara’s rushing waters and abundant land resources as the foundation of an urban-industrial empire. Love called it Model City, a megalopolis that would dominate the region from Lake Ontario to Lake Erie. It would be, he repeated to anyone who might listen, the “most perfect city in existence.”

Although he often spoke in grandiose terms, Love saw himself as a hard-headed industrialist. “Ours is a rational business,” he observed, and “a conscientious endeavor to build a prosperous and booming city.” Love thought his plan fit perfectly with the times, an era when captains of industry built transcontinental railroads, steel plants, and hydroelectric power canals. But Love also saw himself as an industrial reformer. He offered free land to any businesses resettling in the Model City area; he also offered cheap housing to workers. By appealing both to laborers and business leaders, he hoped Model City would thrive socially as well as economically. Love believed his city should be founded on principles of “great architectural beauty.” “We aim at perfection on the broadest possible lines,” he wrote in his first promotional pamphlet.

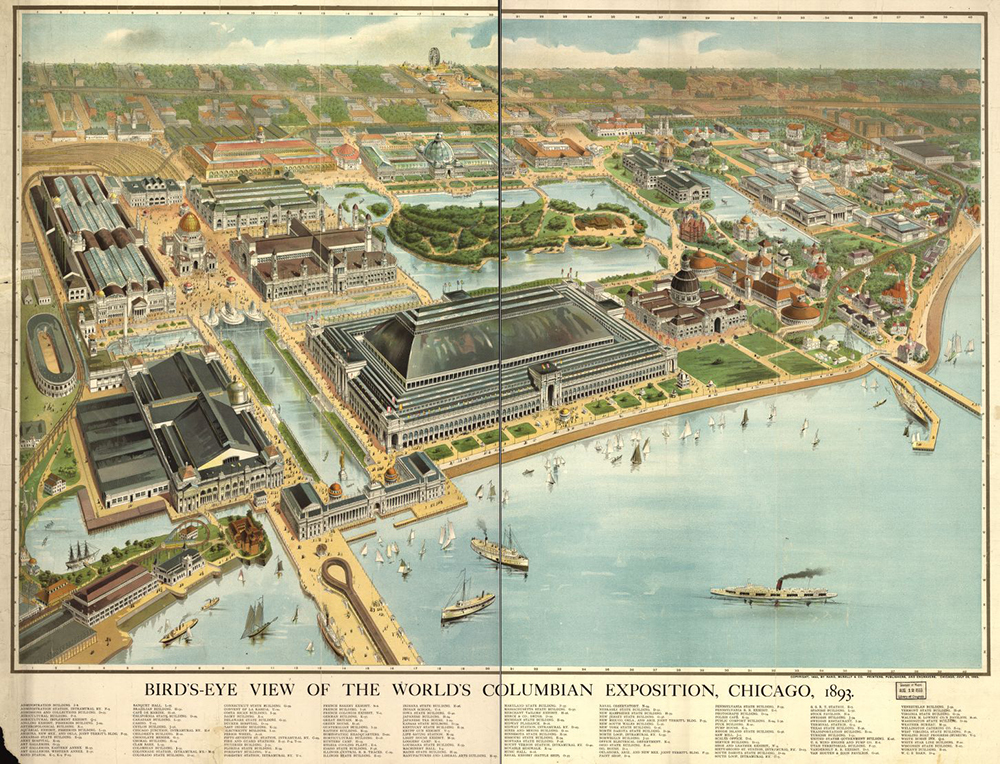

As his dream indicated, Love wanted to be known as an urban progressive. Love lived at a time when, as one scholar has put it, “the city stood at the vital center of transatlantic progressive imaginations.” Puritan John Winthrop had envisioned building a perfect “City Upon a Hill” in the colonial wilderness, and Progressive-era developers like Love sought to rebuild that crumbling edifice through efficient urban planning and management. Chicago’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 exerted a powerful pull on urban visionaries, who saw in Daniel Burnham’s gleaming White City a model environment of clean streets, efficient sanitation services, and little graft or crime. Love hoped Model City would be a well-planned and well-maintained megalopolis that still cared about average people.

Love also saw Model City as a technical wonder. He promised that all homes and businesses would have electrical, telephone, gas, water, and sewer services at a time when such things were far from universal in American life. “Pneumatic conveyers” would provide nearly instantaneous mail service to Model City residents, while pure drinking water would flow through new pipes. Love supported profit-sharing plans for workers, abundant parks for residents, and a brand of urban design that inspired rather than sapped the souls of city dwellers. Borrowing concepts from Henry George’s 1879 Poverty and Progress, which saw class division as the key problem in urban America, Love called for an affordable Model City. Yet where George saw taxation as the way to equalize class relations, Love believed technological innovation—hydroelectricity—combined with access to undeveloped land would spur egalitarianism.

Indeed, with businesses profiting from cheap power, and Model City leaders supporting low rents for workers, Love’s town would avoid the squalor, discontent, and rebellion associated with New York City, Chicago, and Pittsburgh. In those cities, Love claimed, high rent born of urban congestion pushed workers into ramshackle homes. Uprisings often followed. “The Census of 1890 shows cities of 200,000 to 250,000 inhabitants covering 6,000 to 23,000 acres,” he wrote. But Model City would be different, said Love, because the New York State legislature had granted him sway over 10,000 acres of unimproved land a few miles from Niagara Falls. That number was increased to 15,000 and eventually to 30,000 acres, or the equivalent of roughly 50 square miles. And there was the prospect of even more land after that. The company would have the power not only “to buy, sell, and deal land” but “to carry on the work of building a town or city in Niagara County” by any means available. In this famously unregulated era of American industrialization, Love had nearly unrivaled power to secure real estate, alter the land, and build a city ready-made for demographic as well as economic expansion. Love charmed the skeptical Governor R.P. Flower—who had previously vowed to veto the land grant—into supporting Model City. “There will be a city of 2 million inhabitants there,” Flower told a reporter after inking the Model City charter, which granted Love the largest tract of land in New York State history. Flowers’ confidence also gained Love advocates in the business world. J.M. Robinson, president of the First National Bank in Wellsboro, Pa., trumpeted Love’s plan. “I recently visited the Model City,” he wrote. “The site is a perfect one.” The enterprise, he continued, “will prove a great success.” C.M. Loring, head of the North American Telegraph Company of Minneapolis, predicted that Model City would “astonish the world.”

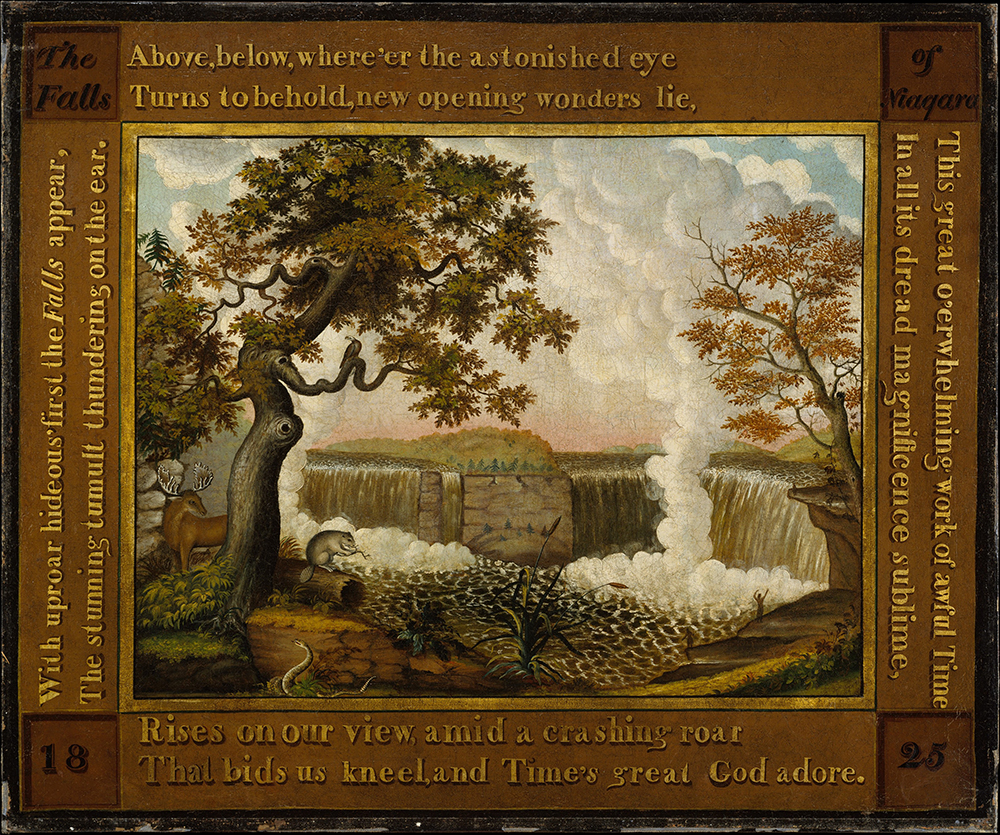

In making such predictions, Love joined other urban visionaries who saw Niagara Falls as a vanguard locale. With clean-burning hydroelectric power, Niagara’s factories would be the antithesis of William Blake’s “dark satanic mills.” One turn-of-the-century industrial agent called Niagara “the coming manufacturing city of America.” Though the city was younger than most metropolises, he observed, its proximity to renewable water resources provided “brighter prospects than any spot in the world.” Lured by the success of several hydroelectric producers, including the Niagara Power Company and the Hydraulic Power Company, hundreds of industrial concerns moved to the region by the early 1900s. Nikola Tesla, the father of alternating current (which allowed companies to get hydroelectric power from farther away), observed in 1897 that the powerhouses lining the Niagara River epitomized nothing less than the human triumph over nature. “We have many monuments of past ages,” he wrote. “The temples of the Greeks and cathedrals of Christendom exemplified the power of man, the greatness of nations, the love of art and religious devotion.” But “that mighty unit at Niagara has something of its own, more in accord with our present thoughts and tendencies.” For Tesla, hydroelectric power meant “the subjugation of natural forces to man.” As he saw it, Niagara Falls was an embodiment of American will.

William Love agreed that the Niagara region already offered the “greatest water power in the world.” But he predicted that his artificial waterfall would soar above every other hydroelectric power project in existence. By diverting water inland over the Lewiston Ledge, Love bragged that he could “double” Niagara’s power. “We are building a canal,” he wrote, “to take water out of the upper and return it into the lower Niagara.” One of Love’s most ardent backers, New York State assemblyman E.T. Ransom, told Love, “What you have already accomplished…satisfies me of the great merit and vitality of the Model City.” So keen was he on Love’s vision that Ransom even recommended this “investment opportunity to my personal friends as an extraordinary one, and am backing it with my own money.”

With so much riding on what became known as Love’s Canal, it is significant that the only surviving picture of William Love shows him not at Model City but at the artificial waterway’s groundbreaking ceremonies on May 23, 1894. The photo captures Love standing proudly at the head of a delegation of politicians, investors, and well-wishers about to turn the first shovel of land for his canal. After the ceremonial dig, Love’s company began excavating the seven-mile river. The big dig held eight contiguous sections, with excavators starting at the Lasalle end of the power canal; another section was soon created near the end of Love’s Canal. But the Lasalle portion would be the most important—that is where Love took would-be investors to show them the progress of his industrial dream. In this way, Love’s grandiose vision took shape almost exactly where the Sieur de Lasalle built the Griffon in 1679; it followed a pathway surveyed in 1835 by William Williams for the ill-fated Niagara Ship Canal. Love was sure town-building glory loomed in the distance.

Using a combination of excavators, derricks, men, and mules, Love’s company plowed a groove of earth about a mile long, 80 feet wide, and 15 feet deep. To continue cutting the canal path, Love had to secure land options from farmers. He also had to maintain funding on the canal itself, as well as on Model City infrastructure: sewers, roads, telephone lines, and buildings. Love always faced funding shortages but his men kept working on the canal. “Signs are not lacking that the enterprise is going to land squarely on its feet,” a reporter wrote of Love’s canal six months after excavations began.

Local newspapers reported that “excavators have already made quite a hole and a big pile of dirt” in Lasalle. To capitalize on this publicity, Love offered public tours of the site. Special trains in downtown Buffalo deposited passengers at a Lasalle depot. Before embarking for Model City, visitors shuffled around the steam excavators plying the canal bed. Each of these machines could do the work of dozens of men, Love said, impressing would-be investors with their manufacturing prowess.

With the canal cutting across the landscape and potential investors touring Model City, Love’s confidence grew. He moved to an affluent Buffalo neighborhood where other industrialists lived. Even though his project was far from finished, Love also listed himself as a “manufacturer” in a city directory. He leased an office in downtown Buffalo and began circulating among bankers and other businessmen. Love was on his way to becoming the greatest industrialist the region had yet seen.

Excavations at Love’s Canal became the measure of Model City’s success. “Everything is reported to be lovely with the Model City Project,” newspaper reporter E.T. Williams wrote in September 1894. The landscape bore the unmistakable signs of a great environmental transformation. Excited by reports of a grand canal being dug outside Niagara Falls, one New York City paper mistakenly claimed that Love’s Canal would be 400 feet wide.

In the wake of his canal-building efforts, Love sold thousands of dollars in bonds, secured options on more Model City land, and began developing residential lots in Model City. Love claimed he had secured bids from “nearly one hundred [firms] from every part of the United States” to build the rest of the canal. Things looked especially bright in December 1894, when two out-of-towners gave Model City a glowing report after “inspecting the canal” and various Model City sites. Thomas Hersey, representing a London syndicate, and Charles Cramer of Louisville, “drove to Lasalle and inspected work already done on the Model City canal,” wrote Williams. Hersey told Love that he should have “no problem” attracting support from London financiers. That was enough for Love. By February 1895, he was in England to meet with British moneymen. “Love is not peddling smoke nor shoveling fog by a long shot,” Williams wrote.

Yet major problems loomed. Investors were worried about the lingering impact of the Panic of 1893, which put as many as 40,000 people out of work in New York and created financial chaos nationally. Many investors wanted surefire investments, not Love’s promise of future returns. Love failed to see that his own land-based dreams often conflicted with his salesmanship, further tipping the scales against the power canal’s completion. Love did not own a single acre of western New York land. Rather, he had license to bargain for any land he sought to transform. Love thus had to attract investors while dealing with Niagara’s farmers. And other companies were looking for real estate along the Niagara Frontier: railroad companies wanting routes to the Falls, new industries searching for access to hydroelectric power grids, investors hoping to flip land for a quick profit.

Niagara’s land boom hit even the sleepiest of locales. A headline in one Buffalo paper proclaimed a Lasalle “real estate boom,” pointing readers’ attention to land speculation in the small town where Love’s Canal was being built. Soon a double-track trolley line would bisect the canal, the paper explained, further increasing property values. “The option men are hustling themselves” in Lasalle, E.T. Williams noted. Others called them “option sharks,” investors who bought land only to charge exorbitant sums for it later. “It is getting to be about like Southern California,” wrote Williams, “where in response to the question, what was raised principally in the section, one was told, the price of land.”

High land prices undercut the funding of Love’s Canal. Land that previously went for $50 per acre now sold for $200, $500, even $1,000 an acre. The minimum amount was $150 per acre. Love expressed particular concern about land values on his trip to London. British investors, he wrote, would underwrite much of the canal and Model City project, but only if William Love could secure big chunks of cheap land. Investors did not want “a checkerboard” of land deals, with some farmers holding out for even higher prices. Love did not have enough money to follow through on his grand plan.

Initially, Love crafted one-year options with local landowners. But before he could attract enough investors, the options expired, and Love had to renegotiate. Work could not proceed fast enough for Love to attract new investors, which meant he could not buy land or continue work on the canal. Finally, in 1896, Love announced that he had signed five-year options with some farmers. But he still had to win farmers’ (and capitalists’) faith. In March 1896, William Love announced he would begin paying farmers in the Lewiston-Porter area of Niagara County a 5 percent down payment for their land. Because he had now secured 30,000 acres, Love promised to pay $750,000. This meant that, in 1896 dollars, Love intended to pay local farmers $15 million—$500 per acre. Land boom or not, no one had yet seen a purchase the size of William Love’s. Yet few people had seen Love’s money, either.

The project still moved forward. In spring 1896, Love sent out a new prospectus to potential investors promising big returns. In one stretch, he dispatched more than 175,000 pieces of mail. In March, he held a lavish banquet for over fifty businessmen at a swank Buffalo hotel, the Iroquois, at which Love “explain[ed] the Model City enterprise” all over again. “Love Conquers All,” one headline read, calling the soirée “a very successful affair.” Love told the audience that he had netted big finances for the scheme, that options had been secured on nearly 30,000 acres of Niagara County land, and that work on the canal would soon restart. A similar jamboree in May 1896, which attracted two dozen national investors, traveled out to the canal, where skeptics would see more than a hundred men working in teams to finish the artificial waterfall. As summer approached, Love bragged that he had over $1 million of investments, with half of that amount pouring in over the last few months.

This time, it really was all hype. Whether he intended to or not, Love essentially ran a Ponzi scheme to pay back investors and farmers whose land options had to be renewed. By August 1896, Love could no longer forestall the obvious: his plan was doomed. Creditors seized items from Love’s Model City office: a printing press, tables, and copies of his company newspapers. Work finally stopped on the power canal. By the following year, all that remained of the Model City dream was the partially finished waterway. It turned out that Love could not conquer all.

For a time, others tried to revive Love’s scheme. F.W. Moore, an original agent for William Love, took over the company newspaper in February 1897. The Niagara Power and Development Company, which held official title to the canal for decades, also underwent reorganization, with different teams of investors seeking to complete a power canal. But nothing definite ever took shape.

Environmental ruin piled on top of financial failure. Even E.T. Williams had to declare that all William Love left Niagara was “a Big Hole in the Ground.” According to a 1908 map of Lasalle, the old power canal was being used by the Niagara County Irrigation and Water Supply Company, perhaps to divert water to area farmers. A few houses took shape in the abandoned canal zone over the next few decades. In summer, local kids used Love’s Canal as a swimming pool; in winter, they skated on it. Few gave any thought to the visionary who once saw the power canal as a gateway to Model City.

After yielding leadership of the company in 1897, William Love headed west. “It will be sometime before Model City will see him again,” a former associate wrote. Love would now help a Canadian businessman run “ten valuable 40 acre tracts of mining land” for the “Manitou and Seine River gold mining company.” Capitalized at $2 million, Love’s new interest was called a “most promising one, now causing great excitement in Canada.” Some Model City backers, including state legislator E.T. Ransom, vowed to purchase stock in it. And many people wished Love well in his new venture. But a few chuckled when they discovered that Love’s new home would be in a small town in western Ontario called Rat Portage.

Love tried to erase his notoriety years later in one last grasp at fame. In 1931, he wrote to President Herbert Hoover about ways to overcome the Great Depression. Now a New Jersey resident, Love hoped to convince Hoover that public works programs were the only way to save the economy and American democracy too. Ever the promoter, he claimed that such schemes would propel America “to the greatest prosperity ever known.” Love then authored a series of articles under the heading, “Prosperity—A Plan to Achieve It.” Yet fame eluded Love again, and he died soon thereafter. As the Niagara Falls Gazette put it, Love was still remembered for his abandoned waterway, which stood as “a monument to dead hopes” in the sleepy town of Lasalle.

Karl Marx said that history is a twice-told tale—the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce. The saga of Love’s Canal reversed that dictum. For William Love’s city-building endeavors became a nearly comedic morality play on big dreams leading to even bigger failures. The next time Love Canal entered the nation’s public consciousness, it was as one of the greatest environmental hazards in modern American history.

Adapted from Love Canal: A Toxic History from Colonial Times to the Present by Richard S. Newman with permission from Oxford University Press. Copyright © 2016 by Richard S. Newman.