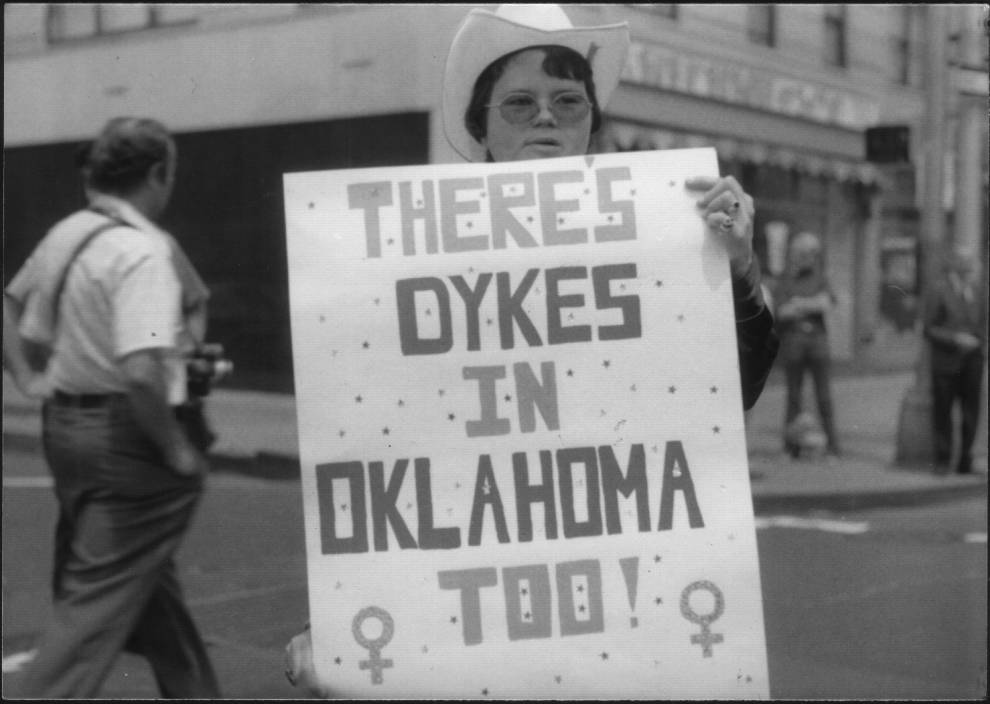

“There’s Dykes in Oklahoma,” 1972. Image courtesy of Lesbian Herstory Archives, Arcus Flynn folder.

In the mid-1970s, Joan Nestle was asked if the Lesbian Herstory Archives—which, in those days, was housed in the pantry of her Upper West Side apartment—would want the papers of a Nazi lesbian organization. Nestle, Jewish and involved in efforts to organize against Israeli occupation, said, “Of course!”

The Lesbian Herstory Archives wanted these papers, just as they wanted newspaper articles, the names of lesbian bars, pins, personal letters, pulp novels, diaries, and term papers. The archive was envisioned not simply as a repository for material that supported the values of lesbian feminists of the 1970s but as a home for sometimes contradictory stories.

In 1969 Betty Friedan, then the president of National Organization for Women, warned that it was necessary to keep the “lavender menace” out of the women’s lib movement. Since then, the way lesbians view themselves and are viewed by the culture at large has changed. In 2016 gay marriage is legal; lesbians, gays, and bisexuals can serve openly in the military; and Jill Soloway’s Transparent makes The L Word seem simplistic in its portrayal of queer culture. The archive has documented these changes and acted as a symbolic home for the diverse strengths and struggles of lesbians.

Today the collection fills a Brooklyn brownstone and is run collectively by a group of volunteers who call themselves coordinators or “archivettes.” These volunteers act as stewards of the world’s oldest and largest collection of material by and about lesbians. (There is another large active collection, June Mazer Lesbian Archive in Hollywood, as well as a smattering of other smaller and less formal collections.) The Lesbian Herstory Archives continues to dedicate itself to documenting the lives of lesbians. It acts as a resource for individuals to do research even as the definition of a lesbian—or, more broadly, a queer person—changes.

Over email, I asked Nestle how she understands the term. “Lesbian,” she writes, “was always a word large enough to encompass all the queerness I have known.” A wide view of lesbianism and the value of inclusion has been necessary in building the archive. She would not have worked for some forty years to form a “role model archives” committed to preserving unblemished stories of lesbian heroes. The idea is an oxymoron. “Let the archive be a place where researchers come to understand how a reactionary queer political class came into being, and what role gay marriage played in turning outlaws into law-and-order voters,” Nestle continued. Quoting a letter she had recently written to the collective, she added: “The archive must be a collector of conversations, not a controller of them. At 76, I know we cannot predict what future communities under siege will need from us. Let us give them all the tracings we can.”

In November 1973 the Gay Academic Union, which advocated for the inclusion in academic institutions of gay individuals and for courses on gay subject matter, held its first conference at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City. Four years after the Stonewall riots, three hundred participants—mostly professors and graduate students—gathered to strategize. During the conference, a woman’s caucus formed to ensure that the voices of lesbians—who were often on the margins of both gay and feminist liberation groups—were heard. The caucus broke into working groups, one of which included Nestle as well as Deborah Edel, Sahli Cavallo, Pamela Oline, and Julia Stanley. The women discussed the trouble they had understanding their own experiences as well as how hard it was to find material about lesbians in libraries. The need to remember the lives of lesbians was clear to them, and a community-based archive was their solution. An archive would act as a repository for stories long ignored by academic and cultural institutions. It would be a resource for lesbians interested in tracing their cultural legacy.

In Imagined Communities, anthropologist Benedict Anderson wrote about how large groups of people—most of whom will never meet—can share experiences and identity. Anderson emphasized how print can transform isolated events into collective experience. The Lesbian Herstory Archives documents both intimate experiences—which are often shrouded in secrecy and shame—and public activism. This documentation helps form an intergenerational consciousness.

The lesbians of the 1970s were largely without a legacy. There are frequent references to Sappho and Amazons in newsletters and magazines from this era. In a 2010 interview Sarah Chinn, the executive director of the Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies at the City University of New York (which, in conjunction with the historian Jonathan Ned Katz, runs OutHistory.org), explained that the 1970s were a key decade in the development of lesbian culture and identity. Women were “learning how to be lesbians in a way that never existed before,” Chinn said. “After that, we had a vocabulary around what it meant. There was a history of women who had been out.”

Without understanding how lesbians had lived in the past, it was difficult to comprehend how it would be possible to navigate the complexities of the present. In an interview that appeared in the fall 1979 issue of the lesbian quarterly Sinister Wisdom, Nestle explained that she understood being a lesbian in the United States meant being trapped in the present without knowledge of a communal past:

I read Albert Memmi’s Colonizer and the Colonized and I started to change the pronouns to she. There was one incredible paragraph about how the colonized are ruled out of time, and how they lose their sense of lineage. The last sentence in the paragraph was, “The colonized are condemned to lose their memory.” It was the word condemned. Condemned. It’s the image of imprisonment to death. Without our memories we are in an endless prison. It became the banner of the Archives, to reverse the condemnation.

At first the archive was just a couple of boxes in Nestle and Edel’s Upper West Side apartment. Volunteers would gather to sort and catalogue the growing collection of periodicals, pulp novels, and photos. When lesbians visited the archive they would find ways to contribute. In that 1979 interview, Nestle said, “‘Oh, you need stationery?’ they’d say, ‘OK, I’ll rip it off from my office,’ or ‘You need Xeroxing? I’ll do that.’”

In 1975, the Lesbian Herstory Archives began sending out a newsletter that included bibliographies, letters, budgets, pictures, and solicitations for donations. Furthermore, it provided information about the archive to lesbians outside the New York area. Lesbians who would never visit the archive could help expand—and be a part of—the collection.

One newsletter offered a memorial for lesbians with “no known survivors.” The phrase frequently appears in obituaries of lesbians, isolating individuals from their communities and their lovers. The archive remembers these women; it saves what it can of what has been left behind—diaries, artifacts, books—and leaves room in its conception of the past for unrecorded lesbian lives. In its newsletter, the Lesbian Herstory Archives encourages lesbians to draw up wills to ensure that their belongings do not end up being destroyed.

In the archive’s early years, archivettes put together a traveling exhibit to present at synagogues, at bars, at universities, and in homes. The exhibit soon transformed into a slideshow. In one iteration, the presentation was made up primarily of photographs of lesbians in their daily lives. “If you have the courage to touch another women,” Nestle and other presenters would tell their audiences, “you are a famous lesbian”—famous for courage, beauty, and intellect. At the end of the presentation, the coordinators would take photos of the women present. These images would become part of the archive and of future presentations.

By the mid-1980s, the collection had moved out of the Upper West Side pantry, expanded throughout Nestle’s apartment, and required space in a nearby apartment and then in offsite storage units. Nestle and Edel always had a vision of the archive surviving past their active participation; they established the Lesbian Herstory Archives as a nonprofit so it would have the protections and privileges (such as lower postal rates) of an independent 501(c)(3). (Nestle has lived in Melbourne for the past ten years but continues to be actively involved in the archive’s decision making.)

In April 1986 more than seven hundred women gathered to raise money for the archive. During the fundraiser, it was announced that the organization would begin saving money to buy a building that would have space for the entire collection as well as room for events. The September 1986 newsletter expanded the campaign. “The national and international lesbian community are our people,” it declared, “and we are making a people’s appeal. Help us raise the funds our home needs. Our dream will come into being not because two or three women give us thousands of dollars, but because thousands of lesbians each give us one dollar.”

A group of women—with Nestle and Edel at its center—had created an archive to record stories. They were now asking those who recognized themselves in these stories to ensure the survival of the collection and its ethos. Buying a building for the collection, rather than just donating the collection to a museum or library, would allow the archive to continue to be overseen by a collective of lesbians and remain open to those without institutional credentials.

Ten years after that initial fundraiser, Edel, the archive’s treasurer, announced that a building—the Park Slope brownstone where the archive is today—had been purchased. A wheelchair lift had been installed, inspections done, floors shined, and curtains hung. In the newsletter Edel tabulated how much it would cost to relocate—a total of $451,168—and announced, “The building is now all of ours.” In a video of the archive’s grand opening in its new location, a women with short hair and sunglasses stands on the steps addressing a joyous crowd: “We will never ever allow ourselves to be hidden, undervalued, diminished, stepped on, disparaged, or forgotten.” Beside her a woman interprets in sign language. Purple balloons blow in the wind behind them.

In the front room of the archives, there are bookcases up to the ceiling, lace curtains, lamps with peach shades and fringe, and a window-unit air conditioner. Throughout are signs saying, “Please no drinks on the shelves.” When I visited in May, Rachel Corbman, an archive coordinator and a gender studies PhD student, showed me around and then let me wander.

On the ground floor, beside the wooden table where Corbmann works, is a file cabinet that holds part of the archive’s photo collection. I opened it and looked at picture upon picture: lesbians on couches and chairs and park benches, lesbians with arms around one another, lesbians protesting and lesbians in bathing suits, lesbians laughing and in love. I was struck by how many lesbians there are and how many there were, and I struggled to understand how these diverse lives coalesce into one identity. How do they fit into a single archive?

In 2011 Flavia Rando founded the Lesbian Studies Institute, which offers the opportunity to study—to make sense of—all the archive holds. The Institute offers a semester-long class taught by Rando. But the institute, like the archive as a whole, does not suppose that any one person can be the ultimate authority on the material. As part of the course, each student is expected to do a project that draws on the archive’s collection. Past projects have included a comic about queer history, a twelve-hour marathon reading of Audre Lorde and Adrienne Rich, and an Instagram account. Each project interprets anew the material in the archive—the endeavors recapitulate the past and allow what was to inform what is.

In a 2013 interview, Rando talked about how archive’s ethos of valuing the knowledge that lesbians have when they come to the archive is important, especially during a time where access is so often determined by wealth and credentials. The determination of the Lesbian Herstory Archives to hold a wide variety of stories and allow anyone to access to—and so to interpret—the collection stands as its own statement: the past was vast, complicated, and filled with paradoxical possibility.