Sunday at the Church of Saint-Philippe-du-Roule, Paris (detail), by Jean Béraud, 1877. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. William B. Jaffe, 1955.

Paris was an embarrassment to Louis XIV. The criminal lieutenant of the police Jacques Tardieu had been murdered, and Civil Lieutenant François Dreux d’Aubray lay dead under suspicious circumstances as well. The king knew that a ruler who was unable to control his capital could be perceived as inefficient or, worse, weak.

He charged Jean-Baptiste Colbert, his trusted minister and controller-general of finance, with the gargantuan task of reforming the police. Nicknamed “le Nord” (the North) for his icy demeanor, Colbert had proved his unwavering dedication to the king when he uncovered a large stash of hidden assets that his predecessor, Cardinal Jules Mazarin, had left behind following his death. Not long after, the king appointed the financially cautious Colbert superintendent of buildings, giving him responsibility for all construction efforts in Paris and at Versailles. A year later, in 1665, his portfolio expanded to include the Ministry of Finance. Colbert had dominion over every area of royal administration except the military—a restriction that would eventually cause much infighting between Colbert and the marquis de Louvois, the minister of war.

Working from his house on the rue Vivienne, just a block from the Royal Library, Colbert built a massive archive that could be drawn on to help both the king and himself make key policy decisions. As “information master” he created a system of state intendants, or bureaucratic informants, who collected and curated reports of activities of interest to the Crown in every aspect of French political, economic, and social life.

Despite his thirst for information, Colbert recognized that there was no way that he could read every report and missive sent by his intendants. He instructed each intendant to distill intelligence into concise and meticulous summaries that he could scan quickly and, on occasion, share directly with the king. Colbert did not disguise his frustration when presented with disorganized or indecipherable reports. “You must make sure to write in large letters,” he told one intendant, “or have your dispatches transcribed, because I am having too much trouble reading them.” In addition to the external intendants, Colbert supported learned academies, such as the newly established Academy of Sciences, with the understanding that he would be the first to hear of their discoveries. He also enlisted an army of scribes, accountants, mapmakers, and couriers to ensure the efficient functioning of his information machine.

For several years Colbert had been impressed by the work of Nicolas de La Reynie, a lawyer from Limoges who had risen methodically through the ranks of the parlement, the highest royal court. The son of a long line of lawyers and magistrates, La Reynie was already well positioned for success in his chosen career. His marriage in 1645 to Antoinette de Barats, the daughter of another well-placed legal family in the region, had strengthened his standing. Still, given that Antoinette’s dowry was relatively small, the twenty-year-old La Reynie likely married her for love rather than social, political, or economic advantage. Whatever the case, the marriage brought good fortune. The following year La Reynie was appointed head of the Bordeaux courts, where he had the final say in the region’s most complex court cases.

While La Reynie set to work establishing his career, the couple wasted no time in starting a family. Within three years Antoinette bore four children. Of the four, only one survived past infancy. Their mother followed them in death in 1648, very possibly from complications in childbirth.

Whether heartbroken, driven, or both, La Reynie plunged himself into his work. It earned him many supporters, and many enemies, in the years following the country’s bitter civil war, the Fronde. The monarchy barely escaped intact from violent uprisings initiated by the nobility between 1648 and 1653 in its effort to take control of the country. To clamp down on dissent, the prime minister arrested three lawyers at the parlement who were leading the movement. The capital exploded with protests. Over the course of two days in late August 1648, Parisians put up more than twelve hundred barricades throughout the city. Soon after, the royal family fled from the Louvre to the safety of the royal residence in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, northwest of Paris.

Ten-year-old Louis was well aware that his life was in danger and could be ended by the frondeurs at any moment. During the five years of conflict that followed, watching his mother, the queen regent, Anne of Austria, and her prime minister, Cardinal Mazarin, fight to save the monarchy, left an indelible mark on the boy.

During the uprisings, La Reynie made his alliance to the Crown clear and refused to allow political troubles to cloud the work of his courts. The powerful duke of Épernon, also a royalist, offered support and protection. When riots broke out in Bordeaux, the two men had little choice but to flee or risk execution. They survived the mob and the Fronde, garnering rewards for their support of the monarchy. The duke of Épernon brought La Reynie’s loyalty to the attention of Cardinal Mazarin. Impressed, Mazarin soon offered La Reynie the position of master of requests (maître de requêtes), responsible for high-level judicial proceedings, in the Paris parlement.

Following the prime minister’s death in 1661, La Reynie’s merits also caught the eye of Mazarin’s successor, Colbert. In 1665, the same year as Tardieu’s murder, La Reynie wrote a meticulously detailed summary of what the country’s disgruntled farmers were saying about the king. “I have learned,” he wrote, “that to save time, you allow your staff to provide you with written reports about matters that you should know about...I would like to take the liberty to share other observations with you, if this is agreeable to you.” The report impressed Colbert. Shortly thereafter he charged La Reynie with the task of reviewing maritime trade and security protocols at the country’s most strategic ports: Marseille, La Rochelle, Nantes, and Rouen.

As La Reynie dug into the work with his characteristic dedication and quiet seriousness, Colbert tackled the problem of how to ensure the safety and security of the country’s most important city. Following the shocking deaths of Tardieu and d’Aubray, the king himself took action. Paris was out of control; it was time to “purge the city of what was causing its disorders”—starting with the archaic and labyrinthine system of policing.

On March 15, 1667, at Colbert’s urging, Louis created the position of lieutenant general of police. Its far-reaching powers included overseeing “city safety, gun control as prescribed by royal ordinances, street cleaning, flood and fire control.” He would police the city’s major markets as well as control any unsanctioned gatherings in Paris. The lieutenant general would also have full supervision of the prisons at the Châtelet complex.

The challenge lay in finding someone who was not so ingrained in the system as to be incapable of the creativity and determination required to assert control over an unruly city. Such a man, Colbert explained to the king, would have to be exceptional if not almost superhuman. The new lieutenant general of police must be “a man of the robe and a man of the sword and, if the doctor’s learned ermine must float upon his shoulder, on his foot must ring the strong spur of the knight.” Colbert continued, “he must be unflinching as a magistrate and intrepid as a soldier; he must not pale before the river in flood or plague in the hospitals, any more than before popular uproar or the threats of your courtiers.”

As Colbert scanned the list of possibilities for a lieutenant general of police, Nicolas de la Reynie’s name rose to the top. No person showed as much dedication to duty and loyalty to those he served as did La Reynie. Although the Fronde was long over, Louis stored in his memory the names of those anti-frondeur nobles who had dared to support the monarchy and stand firm against the uprising. He knew La Reynie had been one of them. The king swiftly approved Colbert’s recommendation, declaring that he could think of no “better man or a more hardworking magistrate” for the job.

Soon after meeting with Colbert on March 20, 1667, La Reynie was appointed lieutenant general of police. In June, La Reynie sat at his desk, quill in hand, and began a letter to Pierre Séguier, the king’s chief of staff. “We are making progress every day on police matters. Much good will come of it, even more so because it will be done without resistance. This will give all inhabitants of this city reason to be grateful that the king wanted to establish law and order in Paris.”

Eager to transform unruly Paris into an idyllic “new Rome” that would serve the glory of his image as the all-powerful Sun King, Louis XIV granted La Reynie unprecedented authority. Operating as police chief and as the equivalent of mayor, La Reynie reached into nearly every corner of late seventeenth-century Parisian life. In this once-dark world, whose inhabitants had been scared to leave their homes after nightfall, lanterns now dotted every throughway and intersection. Newly built fountains relieved residents from their daily trips to the Seine to siphon off its foul waters. A series of well-publicized and forceful police measures were put into place to stave off organized crime—including recently codified procedures for arrest and interrogation sufficiently painful to give even the most hardened criminals pause.

Much of La Reynie’s success came from a tireless work ethic, coupled with an insatiable thirst for information. At all hours of the day and night, couriers on foot and horseback arrived at his compound-like home near the Louvre, on the rue du Bouloi. The couriers delivered updates from the wardens in charge of supervising the city’s overflowing prisons, whose names—the Bastille, the Grand Châtelet, the dungeon of Vincennes—filled Parisians’ hearts with dread. They also brought handwritten accounts from each of the city’s forty-eight commissioners responsible for reporting the daily activities in their local quarter and for enacting La Reynie’s far-reaching orders.

La Reynie received daily updates from a web of civil servants, lawyers, judges, doctors, and merchants from whom he collected endless bits of information. But by far the most interesting missives came from the army of spies and informants that the police chief employed in his efforts to keep crime at bay. Their reports arrived written in invisible ink, stuffed into wigs, or sewn into jackets.

La Reynie reviewed all the reports personally, initialing each page in his unmistakable looping handwriting. He studied every report, deciding which crimes required further investigation and plotting a detailed plan of action for his officers. He also penned daily summaries of his efforts for the king—who studied the police chief’s briefs just as attentively.

Law and order: From his first days as lieutenant general of police in the spring of 1667 to his retirement thirty years later, this was and would remain La Reynie’s prime objective. He started his campaign with a series of ordinances designed to establish unequivocally who was now in charge of cleaning up the streets of Paris. To the grumbling of citizens, La Reynie imposed a “mud tax” on every Parisian who had a lodging or a business within the city—from shops to churches to counts and countesses to the king himself. The tax was intended to offset the substantial costs related to street maintenance. Officials calculated the mud tax based on the length of the facade of the building in which principal owners and renters lived or worked. The tax was paid, in advance, twice a year. There were swift and steep penalties for late payment or refusal to pay, including the immediate confiscation of the inhabitant’s furniture.

La Reynie reached out to well-placed nobles across the city and encouraged them to demonstrate their support. In return the police chief appointed them directors of their quarters. The strategy played into what La Reynie knew to be two common characteristics among the upper classes: a need for recognition and a need for power. The job was more than honorary. Once a year each director submitted a detailed list of all homeowners and their property. It was on the basis of these lists that their fellow inhabitants were taxed and daily expenses for an area’s street cleaning paid.

But what fully set La Reynie’s efforts apart from prior attempts to keep the streets clean was the requirement that every inhabitant of Paris participate. At precisely seven o’clock every morning, hundreds of men ringing large bells moved through the city announcing that it was time for collective cleaning efforts. Parisians young and old, some still rubbing the sleep from their eyes, stumbled out of their houses, brooms in hand, to sweep the filth in front of their homes into the middle of the street. Thirty minutes later thousands of trash collectors were deployed to collect the refuse and haul it outside the city walls.

To aid street-cleaning efforts, new ordinances forbade residents from tying animals outside their homes or leaving the carcasses of dead beasts in public pathways. The long practice of emptying chamber pots from windows was also prohibited. A first offense earned a fine; a second resulted in a beating.

However, La Reynie soon learned with frustration that what residents could no longer throw into the streets they kept in their houses. A commissioner surveying the neighborhoods to the north of the Louvre described the “infection and stink” permeating the insides of homes. They were full of “fecal material and dead animals, a putrefaction that was as large in their homes as it was in the countryside.” Inhabitants continued to relieve themselves on walls, in the streets, and even in the well-populated halls of the Louvre. The call of nature knew no social hierarchies, as some theatergoers learned in 1670 when two noblewomen chucked the contents of a chamber pot from their balcony loge onto the public below “in order to rid their box of the unpleasant smell.”

Still, La Reynie claimed victory over filth a mere three months into his appointment. He crowed that the mud tax had been extraordinarily successful: “Horses are slipping around on the pavement because the streets are so clean now.” It was perhaps a bit of an exaggeration, but no one could argue that the streets weren’t much cleaner.

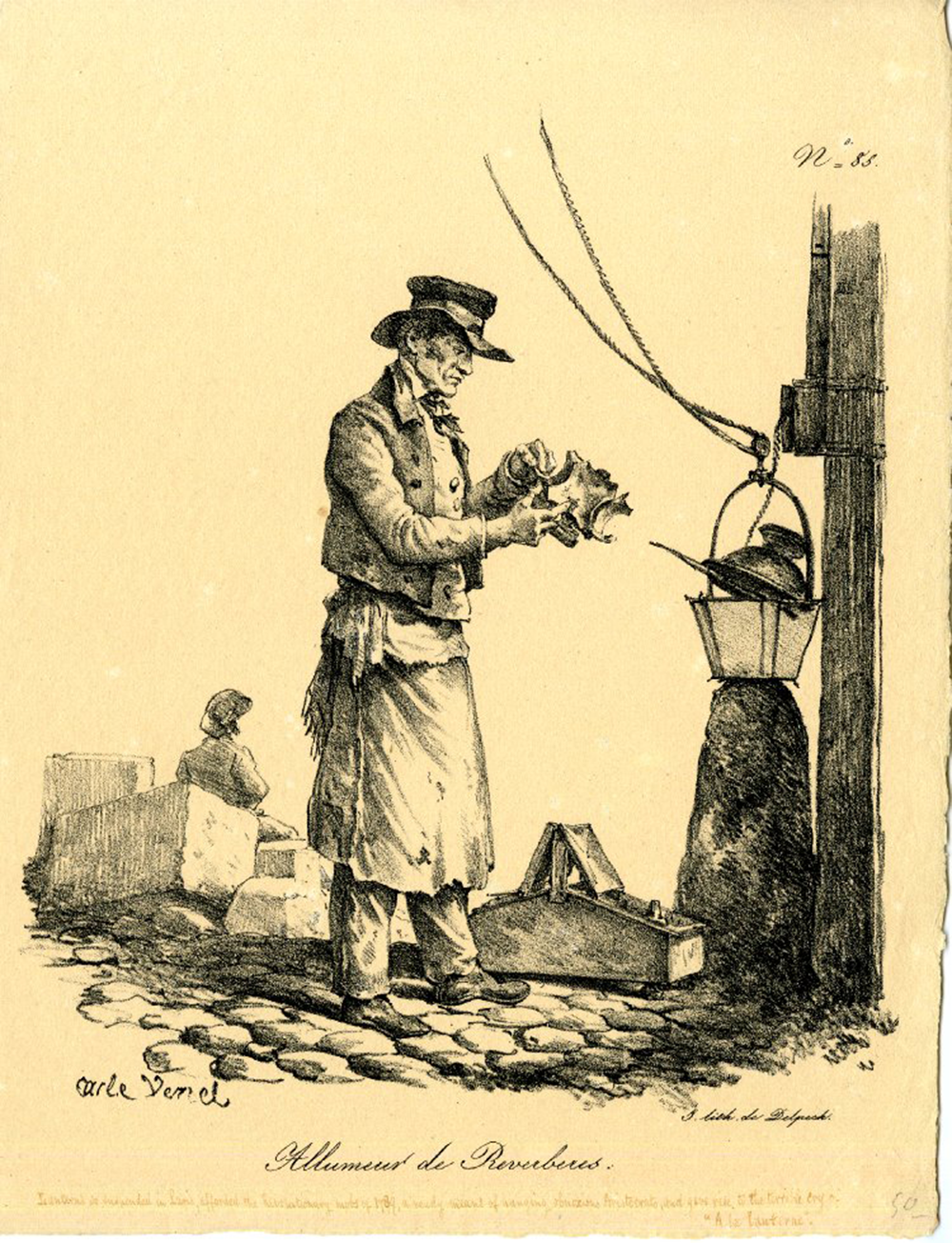

La Reynie’s first months as lieutenant general coincided with the summer, when the long days kept the nights at bay. But with fall approaching and the dark days of winter to come, the police chief faced another problem: Where there was dark, there was crime. La Reynie decided the time had come to end the saga of nighttime thefts and murders occurring throughout the fall and winter. His first course of action was to issue an ordinance imposing public lighting in the city.

In the new ordinance, written in capital letters, La Reynie declared: “We order that, starting the last day of this coming October, candles will be lit in all streets and public places of the city and its surroundings. To this effect, commissioners of each quarter will determine...where lanterns shall be installed and determine the amount that each person in the quarter shall contribute.”

Wanting to leave nothing to chance or misunderstanding, La Reynie provided detailed instructions. The lanterns, which were to be made of sturdy glass in metal housing and stocked with enormous multiwicked candles, should be mounted on the facades of buildings on a flagpole mechanism, allowing for lighting and extinguishing. Once the location and the cost of the lanterns had been decided, each quarter would hold elections to select those responsible for installing and maintaining them. Failure to perform elected duties would result in a stiff fine, which would increase after each instance of neglect. Moreover, property owners would be required to place a lamp in each of their windows and ensure that it remained lit—even on nights when a full moon shone brightly.

“We order,” La Reynie further declared, “that the present ordinance be read and posted everywhere, so that no one can ignore it.” The police chief knew that in a short time his declaration would be typeset and hundreds of copies printed. Within hours, the sounds of drumbeats would fill every quarter as the populace gathered in the streets to listen to public criers read aloud the declaration, which would be on public kiosks, pasted over ever-thickening layers of other official decrees. Members of La Reynie’s police force also fanned out to deliver the ordinance to each of the city’s churches and ordered priests to recite it in their Sunday sermons.

In just a few months, more than one thousand lanterns were installed on the city’s busiest streets. An ornate rooster was painted on each lantern, the symbol of timely vigilance. When La Reynie was done, 2,736 lanterns illuminated the majority of Paris’s streets.

The new lanterns quickly became a target for vandals. In many cases theft or damage was the result of the negligence by a member of the lighting brigade, who had not raised the lantern high enough up and out of reach after lighting the candle. Still, even when they could be raised as high as possible, the lanterns functioned as convenient marks for lackeys, pages, and carriage drivers who saw a tempting target for their whips, canes, and swords. Deeply frustrated by the vandalism, La Reynie issued another ordinance in January 1669 giving anyone who witnessed the destruction of a lantern the right to make a citizen’s arrest. The offense would be considered a felony and punished to the fullest extent of the law.

La Reynie cleaned the streets; he conquered the night. His legacy continues today in Paris’s reputation as the City of Light. The first major European city to be illuminated at night, Paris inspired awe. “Until two or three in the morning,” marveled the journalist François Colletet, “it’s almost as light as daytime.”

Despite the transformation of the Paris night, La Reynie still needed to rein in the thieves, thugs, and other undesirables who made movement around the city a dangerous proposition. The challenge lay in changing the city’s culture of violence. Deadly fights still broke out between carriage drivers jockeying for space in the congested streets, or as packs of men—drunk, armed, and looking for trouble—roamed the city after the taverns closed.

La Reynie issued still more new ordinances to reduce the number of weapons on the streets. He forbade coachmen and other servants from carrying swords, and watched eagerly for opportunities to make an example of offenders. He didn’t have to wait long. When the duke of Roquelaure’s coachman and one of the duchess of Chevreuse’s pages stabbed a student to death on the Pont Neuf, the police chief swiftly had the two men apprehended. They were tried and condemned to a public death by hanging. La Reynie’s intervention met with outrage on the part of the nobles, who complained that the police chief had ignored their long-held rights to control and punish their own servants. The executions took place anyway. As a result La Reynie demonstrated that he held the sole power, with the support of the monarchy, to make all decisions when it came to the collective good of the city.

Like the king, La Reynie was a devout Catholic. He supported, fully and with fervor, the king’s growing interest in policing the morality of his subjects. He imposed a system of fines on the “morally corrupt,” offering up to one-third of the fines as finders’ fees to anyone who reported questionable activities of their fellow city dwellers. One simply had to go to the home of the neighborhood commissioner and make a formal complaint. The commissioner then interviewed witnesses, questioned the accused, and determined guilt. The offenses ranged from swearing to public intoxication and prostitution. In many cases La Reynie got directly involved.

In one of his daily reports to the king, La Reynie shared the case of a man named Orléans who had shouted “execrable blasphemies” after being hit, in his tender parts, during a handball match. Witnesses reported his actions to a local commissioner, who forwarded the case to La Reynie. Knowing that their friend was in trouble, several men raced to La Reynie’s headquarters at Châtelet to offer excuses on the man’s behalf. La Reynie said he would take the matter to the king. However, the man’s fate was by then all but sealed. In his letter La Reynie recommended “a long stay in prison, ordered by His Majesty, [to] allow the man to recognize his error and give him an opportunity to repent.” No record of the ultimate outcome survived, but the odds are very good that the king approved the recommendation.

As part of his effort to address Parisian morality, La Reynie similarly showed no sympathy for the homeless. The earliest forms of hospitals—the hôtels-Dieu (houses of God), as they were called—had originally been established to heal tired and sick Christians traveling on religious pilgrimages. Now, the hôtels-Dieu provided a convenient place to incarcerate the poor, the mentally ill, and prostitutes in order to “reform” them. Living in cramped and unhygienic spaces, they received only minimal sustenance and were threatened with beatings if they did not obey the rules. To ensure full police involvement, La Reynie appointed himself to the board of directors overseeing hospitals, public charities, and orphanages.

Despite some grumbling about La Reynie’s heavy-handedness, the early years of his work as police chief earned him much praise and goodwill throughout the city. “Thanks to your talents,” an appreciative Parisian wrote La Reynie, “everyone feels more secure in Paris...we don’t hear ‘Catch that thief’ anymore. Valets, who are sometimes so insolent, don’t carry swords, don’t insult anymore, and don’t hit people. The number of assassins, poisoners, prostitutes, and blasphemers has decreased, and the streets are much less muddy.” The Mercure Galant, France’s most influential society paper, also praised La Reynie: “Monsieur de la Reynie attempts nothing that does not pass; he has done things since he has been Lieutenant of the Police that were thought impossible, and which many ages attempted in vain. No judge could be more equitable, uncorrupt, or zealous in the service of his King. The populace is so obliged to him, they ought to contrive a way to eternalize his memory.”

Louis XIV agreed, making his own contributions to the praiseworthy propaganda of La Reynie’s work. Two years after the police chief’s appointment, he commissioned a commemorative medal. It featured a woman, the allegorical representation of Paris, holding one of La Reynie’s lanterns in her hand, with the inscription “Security and Clarity of the City 1669.”

Excerpted from City of Light, City of Poison: Murder, Magic, and the First Police Chief of Paris by Holly Tucker. Copyright © 2017 by Holly Tucker. With permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.