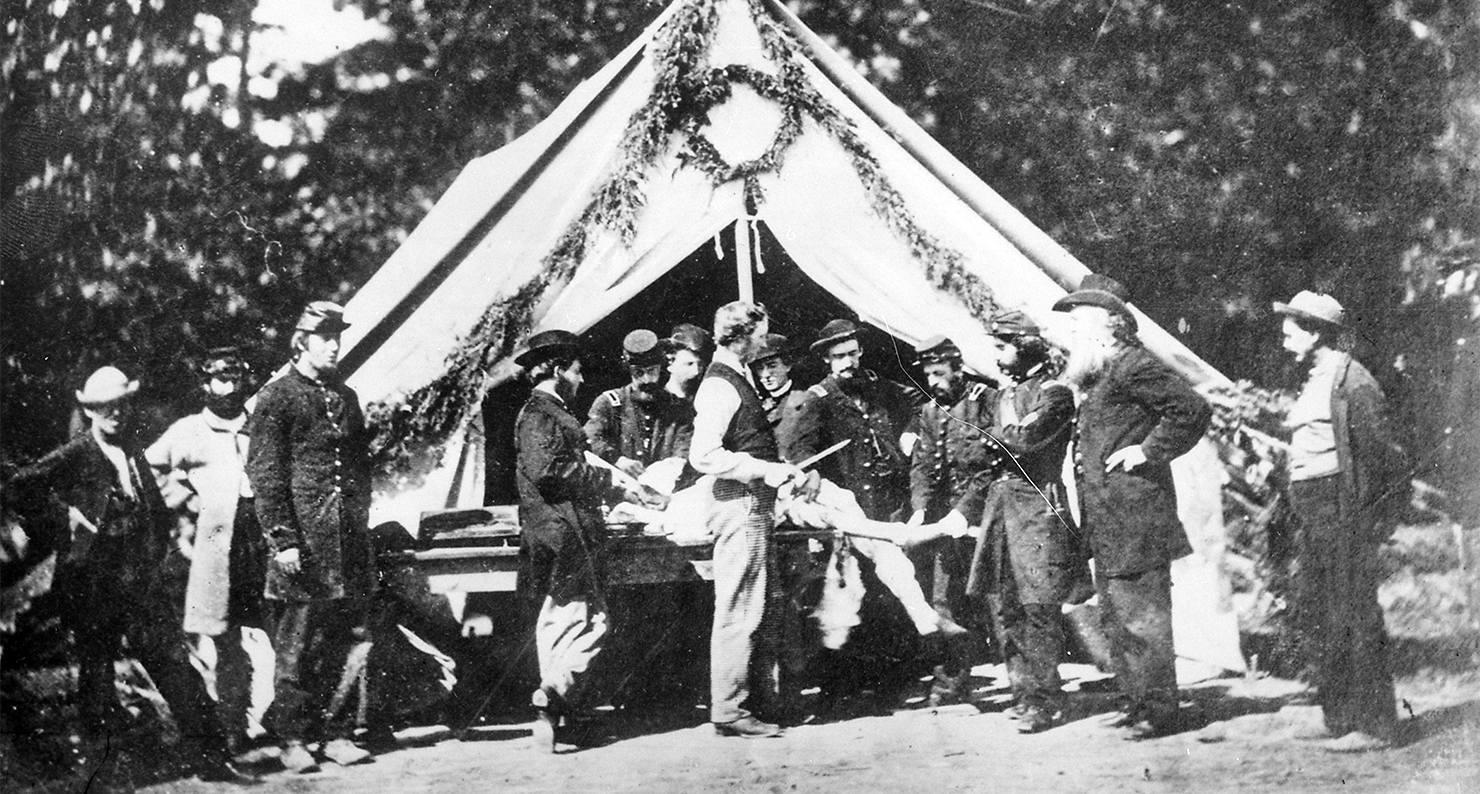

Amputation scene, general Hospital, 1863. Phtograph attributed to Charles J. and Isaac C. Tyson. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland.

The Battle of Gettysburg, fought 150 years ago this week, saw the deaths of more Union and Confederate soldiers than in any other Civil War battle. An estimated 9,000 men were killed during the fight, and another 40,000 were injured. The victorious Union Army, after driving Confederate forces south, stopping their northward advance had much to celebrate and many to mourn, but for those who survived the immediate fighting, a second battle lay ahead in the struggle of the wounded to survive.

Civil War medicine could often be more of a hazard than enemy ambushes. Germ theory, a new-fangled idea that involved hand-washing and instrument sterilization, wasn’t yet in fashion with America’s medical professionals, and keeping bone saws clean on a bloody battlefield was a minor concern.

With limited knowledge and even more limited resources, doctors and surgeons often turned to amputation when a soldier suffered any kind of significant wound. Before the war’s end, some 60,000 men would have a limb removed. Tillie Pierce Alleman, a fifteen-year-old girl whose recollections of Gettysburg during the battle would be published in 1889, observed a grisly scene outside a local home:

To the south of the house, and just outside of the yard, I noticed a pile of limbs higher than the fence. It was a ghastly sight! Gazing upon these, too often the trophies of the amputating bench, I could have no other feeling, than that the whole scene was one of cruel butchery.

Surgeons weren’t just cutting and hoping for the best, though—Samuel Cooper’s The first lines of the practice of surgery was a must-read for any army doctor working on the front lines. Here, we’ve excerpted some of Cooper’s most helpful advice for amputation of the arm, leg, and smaller extremities. It goes without saying—we do not encourage you try this at home:

Arm: The patient may either sit on a chair, or lie near the edge of a bed, and an assistant is to hold the arm in a horizontal position, if the state of the limb will allow it. The pad of the tourniquet is to be applied to the brachial artery, as high as convenient… Instead of making a short stump, when the arm must be taken off very high up, Dr. Larrey thinks it more advisable to amputate at the shoulder joint. He says, that if the humerus is sawn through higher than the insertion of the deltoid muscle, the stump becomes retracted towards the arm-pit by the pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi; the ligatures on the vessels irritate the brachial plexus of nerves; great pain and nervous twitchings are apt to be excited; tetanus is frequently brought on; the stump is affected with considerable swelling; and at length, an anchylosis of the shoulder follows…

Thigh: The thigh should be amputated as low as the disease will allow. The patient is to be placed on a firm table, with his back properly supported by pillows, and assistants, who are also to hold his hands, and keep him from moving too much during the operation. The ankle of the sound limb is to he fastened, by means of a garter, to the nearest leg of the table. An assistant firmly grasping the thigh with both hands, is to draw upward the skin and muscles with some force, while the surgeon makes a circular incision, as quickly as possible, through the integuments, down to the muscles. When the integuments are sound in the place of the incision and above it, their retraction by the assistant as soon as they are cut through, and a very slight division of the bands of cellular substance with the edge of the amputating knife towards the point, will generally preserve a sufficient quantity for covering, in conjunction with the muscles cut in a mode about to be described, the extremity of the bone; and the painful method of dissecting up the skin from the fascia, and turning it back, previously to dividing the muscles, may be considered useless and improper in all amputations of the thigh, where the skin retains its natural movableness and elasticity…

Fingers and Toes: The operation may be done in various ways. Sometimes a small semilunar incision is made on the back of the finger or toe to be amputated, extending across the part with its greatest convexity about half an inch beyond the joint. The Rap is next raised, and reflected. The skin on the other side directly opposite the joint, is divided by a second cut, extending across the finger, or toe, and meeting the two ends of the first semilunar incision. The joint is now bent, and the capsular ligament opened. One of the lateral ligaments is then divided, which allows the head of the bone to be dislocated, and the surgeon has nothing more to do, than to cut such other parts, as still attach the part, about to be removed, to the rest of the limb. When the arteries bleed profusely, they must be tied; but, in general, the hemorrhage will stop without a ligature, as soon as the flap is applied to the end of the stump, and the edges of the wound have been brought together with adhesive plaster. Of the plan of stopping the bleeding by pinching the vessels, sometimes recommended, I can say nothing from my own experience.