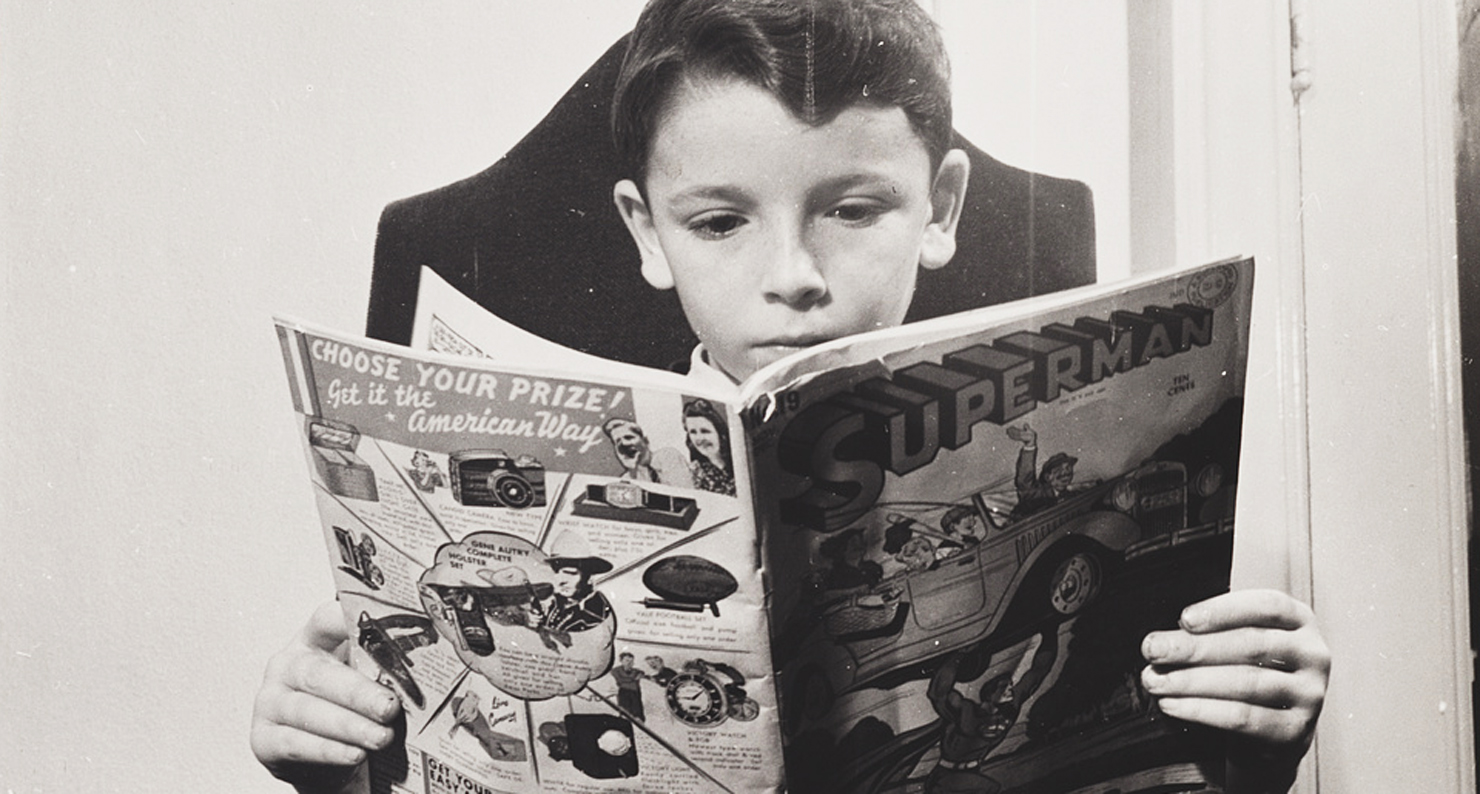

A German-refugee child reads a Superman comic, 1942. Library of Congress.

In October 1948, the students of Spencer Graded School in Roane County, West Virginia, gained national attention when thirteen-year-old David Mace led his classmates in “burial rites” for their comic books. Newspapers cast Mace, costumed in black slacks and a white shirt, as a grave and sober preacher figure. Mace solemnly reminded the school’s six hundred students that they were meeting “here today to take a step which we believe will benefit ourselves, our community and our country.” Comic books, he said, “are mentally, physically, and morally injurious to boys and girls, [and] we propose to burn those in our possession.”

The “cremation” represented the culmination of a month-long campaign in which Mace, an eighth grader recruited to the cause by his reading teacher, Mabel Riddel, who devoted one class each week to Bible study, had led more than 250 students in a door-to-door collection drive that netted two thousand comic books. The pile was six feet high, but it likely didn’t represent the entirety of the schoolchildren’s comics; one student recalled that he had “selected my oldest, most worn, least valuable comic books to bring,” leaving “all of them that were any good at home.”

Before he started the blaze with a Superman comic, Mace first led the assembled students in a dramatic call and response:

“Do you, fellow students, believe that comic books have caused the downfall of many youthful readers?”

We do.”

“Do you believe that you will benefit by refusing to indulge in comic book readings?”

“We do.”

“Then let us commit them to the fire.”

The fire lasted over an hour, the flames reaching more than twenty-five feet. While Mrs. Riddel stared into the flames, some of the children cried.

The invective against comic books followed a well-worn rhetorical pattern. In 1883, anti-obscenity crusader Anthony Comstock called dime novels, introduced shortly before the Civil War, “boy and girl devil-traps [that] are ruining hundreds of youth.” A U.S. postal inspector and founder of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, Comstock was responsible for the 1873 law that made illegal the distribution of “obscene, lewd, or lascivious” material through the mail. Comstock forcefully argued that dime novels “stimulated ambition” in young readers to “imitate deeds of bloodshed and desperation” and were related to every case of violent juvenile crime.

Such logic was fueled by the sensational trial of dime novel enthusiast Jesse Pomeroy a fifteen-year-old Bostonian who brutally murdered two small children in 1874. Observers claimed that the cheap Western novels he loved had inspired his crimes. Generally, though, such claims were largely a matter of tenuous correlation: dime novels were widely circulated, cheap, and readily available to teenagers like Pomeroy; teenagers sometimes committed heinous crimes; therefore a teenager like Pomeroy must have found inspiration in the novels.

Like dime novels, comics were also extraordinarily popular. The genre took off in the late 1930s, embraced by both children and adults; during World War II, comics made up a quarter of the reading material available at American military exchanges. By the end of the decade, between eight and ten million comics were sold each month, most of them priced at ten cents (about one dollar today). Their circulation was often far greater than sales figures indicated; one popular crime comic sold around one million copies a month, and each copy was passed around to “another six to ten readers.”

The 1948 conflagration at Spencer Graded School was one of fifteen comic-book burnings that took place in post-war communities throughout the United States, which are examined in great detail in David Hadju’s 2008 book The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America. They were part of a moral panic over comic books that occupied Americans through the mid-1950s. Comics were a convenient target for a range of anxieties prompted by the war and its aftermath, particularly an apparent juvenile delinquency crisis, fueled by unreliable crime statistics from both the FBI and the U.S. Children’s Bureau, and by rhetoric that emphasized moral and social erosion. J. Edgar Hoover himself was “shocked and alarmed.”

The arrests of teenage boys and girls all over the country are staggering. Some of the crimes youngsters are committing are almost unspeakable. Prostitution, murder, rape. These are ugly words. But it is an ugly situation. If we are to correct it, we must face it.

Mass media would increasingly be blamed for growing juvenile crime rates. But on the ground, its influence was negligible. In a pair of papers published in 1938, sociologist Paul Cressey had already demonstrated that “movies did not have any significant effect in producing delinquency,” and similar findings emerged for radio, television, and the comics. In 1950, a Senate subcommittee investigation into organized crime would find “no direct connection between the comic books dealing with crime and juvenile delinquency.” But the solution to the panic would be mustered not from scientific study or government oversight, but fueled by popular media itself.

The first reported comic-book burning took place in November of 1945 in Wisconsin Rapids, Wisconsin, a town of eleven thousand located about a hundred miles north of Madison. The children of Saints Peter and Paul School torched 1,567 comic books accumulated during a school-sponsored collection drive, all titles which a Catholic censor had classified as “condemned” (Batman, The Green Hornet, Wonder Woman) or “questionable” (Dick Tracy, Orphan Annie, L’il Abner). Two years later, students at Chicago’s St. Gall’s School burned three thousand comics after a collection drive organized at the impetus of a ten-year-old student.

These incidents at first received little national attention. The fervor for destroying comic books only caught fire when Frederic Wertham brought the issue to the fore in the spring of 1948. Wertham, the German-born director of psychiatry at Queens Hospital, had also founded the Lafargue Clinic, the first mental health clinic in Harlem. Basing his claims on his extensive study of the children and teenagers he treated there, Wertham debuted as an expert on the subject in Collier’s in March 1948 in an interview titled “Horror in the Nursery.” Two months later, his essay “The Comics—Very Funny!” appeared in the Saturday Review of Literature; a condensed version appeared in the widely read Reader's Digest in August.

Wertham named many cases in which comic books had inspired violent juvenile crimes—though his argument was merely one of correlation. In Collier’s he named the case of seventeen-year-old Francis Muskavitch, sentenced to twenty-five years to life for the murder of a Bronx storekeeper, expressing astonishment that “judges and district attorneys nevertheless tolerate the invitation of and inspiration to armed robbery offered in millions of comic books.” But none of the reports on Muskavitch’s apprehension and conviction mention comics; a more likely influence was that he was intoxicated during the holdup.

A rash of widely circulated news items convinced many Americans that Wertham was right. In May, two fifth grade boys in Oklahoma City, claiming they “learned to fly by reading comic books,” absconded with a two-engine Cessna and safely completed a 150-mile flight. Days before the Spencer comic book burning, an AP story reported that sixteen-year-old Joseph Manuel committed eight armed robberies and murdered a forty-year-old man because the youth “read comic books and listened to gangster stories on the radio all the time when he was at home.”

In May 1948, fourteen-year-old David Wigransky responded to Wertham’s piece in the Saturday Review with an eloquent letter to the editor. In late July, after contacting his high school principal to confirm that the letter was real, the magazine devoted a page and a half to the doctor’s lengthy essay. “I sincerely doubt,” the teenager wrote,

if the children and adolescents interviewed by Dr. Wertham would even bring up the subject of comic books at all if he did not first bring it up himself. Being a psychiatrist, he must be able to do an expert job of leading them on, mixing them up, getting them excited, and generally unnerving them. He stirs them up over the subject…just as he has the ability to do on any subject, and then records their nervously blurted-out remarks to use in his attacks on comic books.

While some readers wrote in to question the veracity of the letter, others were “delighted” that the young man reminded “some rather smug adults that they allow their own literature to be ‘vulgar…vicious…depraving…’”

The fourteen-year-old’s elegant reminder that “any who starts to raise his voice in protest to this generation [should] first compare it with any preceding one” fell on deaf ears, as did evidence that mass media was not responsible for juvenile crime. That fall Mrs. Riddel, David Mace and the students of Spencer Graded School in West Virginia would cleanse their comic book anxiety with fire.

Public alarm bore little relationship to reality. After the panic of the 1950s, public concern over mass media fell to new lows after 1960, despite a significant jump in juvenile crime rates. Dr. Wertham would return as the star of the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency’s 1954 hearings about comic books. He reiterated his old arguments in a new book, The Seduction of the Innocent, which went into a second printing later that year. Though the committee sheepishly conceded that there was no clear relationship between juvenile crime rates and comic book content, one senator told a television interviewer that he believed comics were “directly responsible for a substantial amount of juvenile delinquency and public crime.”

The moral panic over mass media is an old story we revive when we need to make sense of a seemingly brutal and unstable world, one that stubbornly resists reality. Six weeks after twenty-year-old Adam Lanza killed twenty children and six adults at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, in December 2012, Senator Christopher Murphy laid the blame on video games. Speaking at a conference introducing legislation to ban assault weapons, he suggested that the massacre might not have happened if Lanza hadn't had “access to a weapon that he saw in video games that gave him a false sense of courage about what he could do that day.” There was, of course, no evidence that they played any role. These fearful narratives about mass media are as outlandish and fantastic as the cartoon goons, comic book villains, and video game monsters blamed for damaging “the children” in a very real war of good versus evil.

The 1954 Senate committee hearings would establish a Comics Code Authority that would monitor the content in comic books according to a strict set of rules, beginning with the following:

1. Crimes shall never be presented in such a way as to create sympathy for the criminal, to promote distrust of the forces of law and justice, or to inspire others with a desire to imitate criminals.

2. In every instance good shall triumph over evil, and the criminal shall be punished for his misdeeds.