I humbly submit that Buddhism is but one of the religious systems obtaining among the barbarian tribes, that only during the later Han dynasty did it filter into the Middle Kingdom, and that it never existed in the golden age of the past.

It was not until the reign of Mingdi of the Han that Buddhism first appeared. His reign lasted no longer than eighteen years, and after him disturbance followed upon disturbance, and reigns were all short. From the time of the five dynasties, Song, Qi, Liang, Chen, and Yuan Wei onward, as the worship of Buddha slowly increased, dynasties became more short-lived. Wudi of Liang alone reigned as long as forty-eight years. During his reign he three times consecrated his life to Buddha, made no animal sacrifices in his ancestral temple, and ate but one meal a day of vegetables and fruit. Yet in the end he was driven out by the rebel Hou Jing and died of starvation in Tai-cheng, and his state was immediately destroyed. By worshipping Buddha he looked for prosperity but found only disaster—a sufficient proof that Buddha is not worthy of worship.

When Gaozu succeeded the fallen house of Sui, he determined to eradicate Buddhism. But the ministers of the time were lacking in foresight and ability, they had no real understanding of the way of the ancient kings, nor of the things that are right both for then and now. Thus they were unable to assist the wise resolution of their ruler and save their country from this plague. To my constant regret the attempt stopped short. But you, your majesty, are possessed of a skill in the arts of peace and war, of wisdom and courage the like of which has not been seen for several thousand years. When you first ascended the throne you prohibited recruitment of Buddhist monks and Daoist priests and the foundation of new temples and monasteries and I firmly believed that the intentions of Gaozu would be carried out by your hand, or if this were still impossible, that at least their religions would not be allowed to spread and flourish.

And now, your majesty, I hear that you have ordered all Buddhist monks to escort a bone of the Buddha from Fengxiang and that a pavilion be erected from which you will in person watch its entrance into the Imperial Palace. You have further ordered every Buddhist temple to receive this object with due homage. Stupid as I am, I feel convinced that it is not out of regard for Buddha that you, your majesty, are praying for blessings by doing him this honor, but that you are organizing this absurd pantomime for the benefit of the people of the capital and for their gratification in this year of plenty and happiness. For a mind so enlightened as your majesty’s could never believe such nonsense. The minds of the common people however are as easy to becloud as they are difficult to enlighten. If they see your majesty acting in this way, they will think that you are wholeheartedly worshipping the Buddha, and will say, “His majesty is a great sage, and even he worships the Buddha with all his heart. Who are we that we should any of us grudge our lives in his service?” They will cauterize the crowns of their heads, burn off their fingers, and in bands of tens or hundreds cast off their clothing and scatter their money and from daylight to darkness follow one another in the cold fear of being too late. Young and old in one mad rush will forsake their trades and callings and, unless you issue some prohibition, will flock round the temples, hacking their arms and mutilating their bodies to do him homage. And the laughter that such unseemly and degenerate behavior will everywhere provoke will be no light matter.

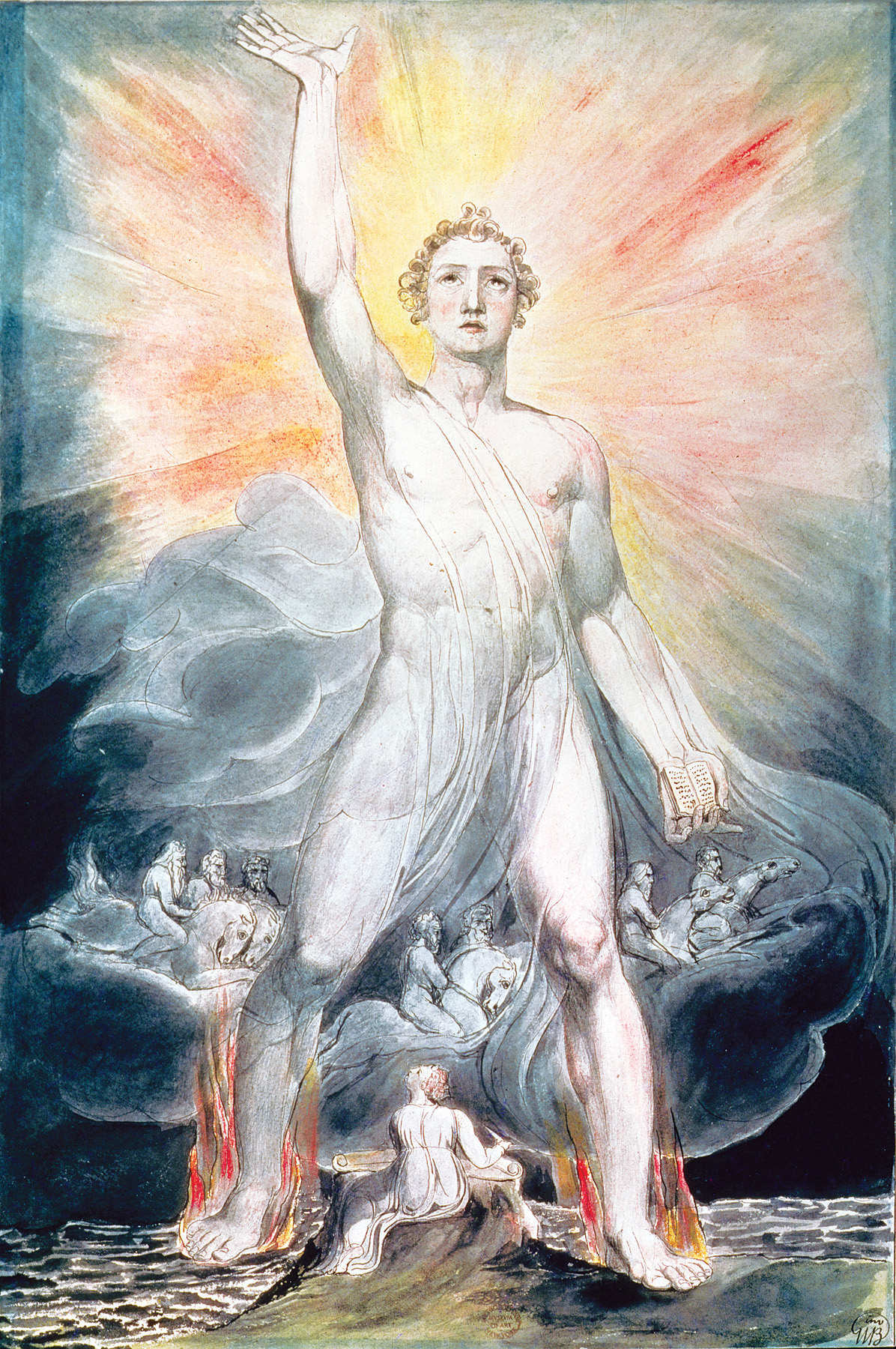

Angel of the Revelation, by William Blake, c. 1803–05. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1914.

The Buddha was born a barbarian; he was unacquainted with the language of the Middle Kingdom, and his dress was of a different cut. His tongue did not speak nor was his body clothed in the manner prescribed by the kings of old; he knew nothing of the duty of minister to prince, or the relationship of son to father. Were he still alive today, were he to come to court at the bidding of his country, your majesty would give him no greater reception than an interview in the Strangers’ Hall, a ceremonial banquet, and the gift of a suit of clothes, after which you would have him sent under guard to the frontier to prevent him from misleading your people. There is then all the less reason now that he has been dead so long for allowing this decayed and rotten bone, this filthy and disgusting relic to enter the Forbidden Palace. “I stand in awe of supernatural beings,” said Confucius, “but keep them at a distance.” And the feudal lords of olden times when making a visit of condolence even within their own state would still not approach without sending a shaman to precede them and drive away all evil influences with a branch of peach wood. But now and for no given reason your majesty proposes to view in person the reception of this decayed and disgusting object without even sending ahead the shaman with his peach-wood wand—and to my shame and indignation none of your ministers says that this is wrong, none of your censors has exposed the error.

I beg that this bone be handed over to the authorities to throw into water or fire, that Buddhism be destroyed root and branch forever, that the doubts of your people be settled once and for all and their descendants saved from heresy. For if you make it known to your people that the actions of the true sage surpass ten thousand times ten thousand those of ordinary men, with what wondering joy will you be acclaimed! And if the Buddha should indeed possess the power to bring down evil, let all the bane and punishment fall upon my head, and as heaven is my witness I shall not complain.

In the fullness of my emotion, I humbly present this memorial for your attention.

From Memorial on the Bone of Buddha. For his spirited attack on Buddhism, Han Yu nearly lost his life; the emperor’s request for capital punishment was commuted to a one-year banishment to South China. A poet, essayist, and early proponent of neo-Confucianism, Han Yu received the official honorary epithet “Master of Letters” upon his death.

Back to Issue