May 8

Senate formed. The secretary, as usual, had made some mistakes, which were rectified, and now Mr. Elsworth moved for the report of the joint committee to be taken up on the subject of titles to add to “President.” It was accordingly done. Mr. Lee led the business. He took his old ground—all the world, civilized and savage, called for titles; that there must be something in human nature that occasioned this general consent; that, therefore, he conceived it was right.

Mr. Elsworth rose. He had a paper in his hat, which he looked at constantly. He repeated almost all that Mr. Lee had said, but got on the subject of kings—declared that the sentence in the primer of fear God and honor the king was of great importance; that kings were of divine appointment; that Saul, head and shoulders taller than the rest of the people, was elected by God and anointed by his appointment.

I sat, after he had done, for a considerable time, to see if anybody would rise. At last I got up and first answered Lee as well as I could with nearly the same arguments, drawn from the Constitution. I mentioned that within the space of twenty years back, more light had been thrown on the subject of governments and on human affairs in general than for several generations before; that this light of knowledge had diminished the veneration for titles, and that mankind now considered itself as little bound to imitate the follies of civilized nations as the brutalities of savages; that the abuse of power and the fear of bloody masters had extorted titles as well as adoration, in some instances from the trembling crowd; that the impression now on the minds of the citizens of these states was that of horror for kingly authority.

The vice president repeatedly helped the speakers for titles. Elsworth was enumerating how common the appellation of “President” was. The vice president put him in mind that there were presidents of fire companies and of a cricket club. Mr. Lee at another time was saying he believed some of the states authorized titles by their constitutions. The vice president, from the chair, told him that Connecticut did it. At sundry other times he interfered in a like manner.

I collected myself for a last effort. I read the clause in the Constitution against titles of nobility; showed that the spirit of it was against not only granting titles by Congress but against the permission of foreign potentates granting any titles whatever; that as to kingly government, it was equally out of the question, as a republican government was guaranteed to every state in the Union; that they were both equally forbidden fruit of the Constitution. I called the attention of the house to the consequences that were like to follow; that gentlemen seemed to court a rupture with the other house. The representatives had adopted the report and were this day acting on it, or according to the spirit of the report. We were proposing a title. Our conduct would mark us to the world as actuated by the spirit of dissension, and the characters of the houses would be as aristocratic and democratic.

The report of the Committee on Titles was, however, rejected. “Excellency” was moved for as a title by Mr. Izard. It was withdrawn by Mr. Izard, and “Highness,” with some prefatory word, proposed by Mr. Lee. Now long harangues were made in favor of this title. “Elective” was placed before. It was insisted that such a dignified title would add greatly to the weight and authority of the government both at home and abroad. I declared myself totally of a different opinion; that at present it was impossible to add to the respect entertained for General Washington; that if you gave him the title of any foreign prince or potentate, a belief would follow that the manners of that prince and his modes of government would be adopted by the president. (Mr. Lee had, just before I got up, read over a list of the titles of all the princes and potentates of the earth, marking where the word “Highness” occurred. The Grand Turk had it, all the princes of Germany had it, sons and daughters of crowned heads, etc.) That particularly “Elective Highness,” which sounded nearly like “Electoral Highness,” would have a most ungrateful sound to many thousands of industrious citizens who had fled from German oppression; that “Highness” was part of the title of a prince or princes of the blood and was often given to dukes; that it was degrading our president to place him on a par with any prince of any blood in Europe, nor was there one of them that could enter the list of true glory with him.

But I will minute no more. The debate lasted till half after three o’clock, and it ended in appointing a committee to consider a title to be given to the president. This whole silly business is the work of Mr. Adams and Mr. Lee; Izard follows Lee, and the New England men, who always herd together, follow Mr. Adams. Mr. Thompson says this used to be the case in the old Congress. I had, to be sure, the greatest share in this debate and must now have completely sold (no, sold is a bad word, for I have got nothing for it) every particle of court favor, for a court our house seems determined on, and to run into all the fooleries, fopperies, fineries, and pomp of royal etiquette; and all this for Mr. Adams.

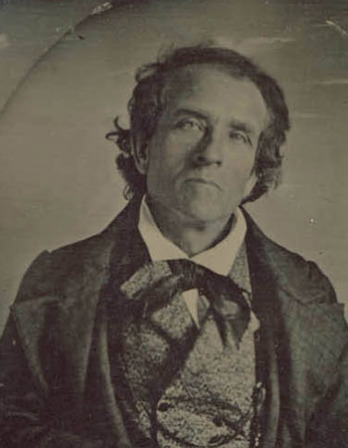

From his Journal. Maclay fought in the French and Indian and Revolutionary wars, later serving in the Pennsylvania state legislature in the early 1780s and in the first U.S. Senate under the Constitution, from 1789 to 1791. His journals were first published in 1880 and are now thought to be the only continuous record of the early federal period. In them he notes that George Washington, when asked to take his oath of office as president, “seemed to have forgot half what he was to say, for he made a dead pause and stood for some time, to appearance, in a vacant mood.”

Back to Issue