I love everyone now that I have gray hair.

—Polatkin, 1855All-Nighter

Walt Whitman tends to the wounded the best he can.

December 21, 1862

Began my visits among the camp hospitals in the Army of the Potomac. Spent a good part of the day in a large brick mansion, on the banks of the Rappahannock, used as a hospital since the battle—seems to have received only the worst cases. Outdoors, at the foot of a tree, within ten yards of the front of the house, I notice a heap of amputated feet, legs, arms, hands, etc., a full load for a one-horse cart. Several dead bodies lie near, each covered with its brown woolen blanket. In the dooryard, toward the river, are fresh graves, mostly of officers, their names on pieces of barrel staves or broken board, stuck in the dirt. (Most of these bodies were subsequently taken up and transported north to their friends.)…The large mansion is quite crowded, upstairs and down, everything impromptu, no system, all bad enough, but I have no doubt the best that can be done; all the wounds pretty bad, some frightful, the men in their old clothes, unclean and bloody. Some of the wounded are rebel soldiers and officers, prisoners. One, a Mississippian—a captain—hit badly in leg, I talked with some time; he asked me for papers, which I gave him. (I saw him three months afterward in Washington, with his leg amputated, doing well.)…I went through the rooms, downstairs and up. Some of the men were dying. I had nothing to give at that visit, but wrote a few letters to folks home, mothers, etc. Also talked to three or four, who seemed most susceptible to it, and needing it.

(Everything is quiet now, here about Falmouth and the Rappahannock, but there was noise enough a week or so ago. Probably the earth never shook by artificial means, nor the air reverberated, more than on that winter daybreak of eight or nine days since, when General Burnside ordered all the batteries of the army to combine for the bombardment of Fredericksburg. It was in its way the most magnificent and terrible spectacle, with all the adjunct of sound, throughout the war. The perfect hush of the just-ending night was suddenly broken by the first gun, and in an instant all the thunderers, big and little, were in full chorus, which they kept up without intermission for several hours.)

December 23–31

The results of the late battles are exhibited everywhere about here in thousands of cases, (hundreds die every day), in the camp, brigade, and division hospitals. These are merely tents, and sometimes very poor ones, the wounded lying on the ground, lucky if their blankets are spread on layers of pine or hemlock twigs or small leaves. No cots; seldom even a mattress. It is pretty cold. The ground is frozen hard, and there is occasional snow. I go around from one case to another. I do not see that I do much good, but I cannot leave them. Once in a while some youngster holds on to me convulsively, and I do what I can for him; at any rate, stop with him and sit near him for hours, if he wishes it.

Besides the hospitals, I also go occasionally on long tours through the camps, talking with the men, etc. Sometimes at night among the groups around the fires, in their shebang enclosures of bushes. These are curious shows, full of characters and groups. I soon get acquainted anywhere in camp, with officers or men, and am always well used. Sometimes I go down on picket with the regiments I know best…As to rations, the army here at present seems to be tolerably well supplied, and the men have enough, such as it is, mainly salt pork and hardtack. Most of the regiments lodge in the flimsy little shelter tents. A few have built themselves huts of logs and mud, with fireplaces.

Washington, DC—January 21, 1863

Devoted the main part of the day to Armory Square Hospital; went pretty thoroughly through Wards F, G, H, and I; some fifty cases in each ward. In Ward F supplied the men throughout with writing paper and stamped envelope each; distributed in small portions, to proper subjects, a large jar of first-rate preserved berries, which had been donated to me by a lady—her own cooking. Found several cases I thought good subjects for small sums of money, which I furnished. (The wounded men often come up broke, and it helps their spirits to have even the small sum I give them.) My paper and envelopes all gone, but distributed a good lot of amusing reading matter; also, as I thought judicious, tobacco, oranges, apples, etc. Interesting cases in Ward I; Charles Miller, bed No. 19, Company D, 53rd Pennsylvania, is only sixteen years of age, very bright, courageous boy, left leg amputated below the knee; next bed to him, another young lad very sick; gave each appropriate gifts. In the bed above, also, amputation of the left leg; gave him a little jar of raspberries; bed No. 1, this ward, gave a small sum; also to a soldier on crutches, sitting on his bed near…(I am more and more surprised at the very great proportion of youngsters from fifteen to twenty-one in the army. I afterward found a still greater proportion among the Southerners.)

Summer of 1864

Dotting a ward here and there are always cases of poor fellows, long-suffering under obstinate wounds, or weak and disheartened from typhoid fever, or the like; marked cases, needing special and sympathetic nourishment. These I sit down and either talk to or silently cheer them up. They always like it hugely (and so do I). Each case has its peculiarities, and needs some new adaptation. I have learned to thus conform—learned a good deal of hospital wisdom. Some of the poor young chaps, away from home for the first time in their lives, hunger and thirst for attention. This is sometimes the only thing that will reach their condition.

In these wards, or on the field, as I thus continue to go around, I have to adapt myself to each emergency, after its kind or call, however trivial, however solemn—every one justified and made real under its circumstances—not only visits and cheering talk and little gifts—not only washing and dressing wounds (I have some cases where the patient is unwilling anyone should do this but me)—but passages from the Bible, expounding them, prayer at the bedside, explanations of doctrine, etc. (I think I see my friends smiling at this confession, but I was never more in earnest in my life.)

Gifts—Money—Discrimination

As a very large proportion of the wounded still come up from the front without a cent of money in their pockets, I soon discovered that it was about the best thing I could do to raise their spirits, and show them that somebody cared for them, and practically felt a fatherly or brotherly interest in them, to give them small sums, in such cases, using tact and discretion about it. I am regularly supplied with funds for this purpose by good women and men in Boston, Salem, Providence, Brooklyn, and New York. I provide myself with a quantity of bright, new ten-cent and five-cent bills and, when I think it incumbent, I give twenty-five or thirty cents, or perhaps fifty cents, and occasionally a still larger sum to some particular case.

Citizens of Paris Offering Their Jewels to the National Convention, by Jean-Baptiste Lesueur, c. 1790. © Musee de la Ville de Paris, Musee Carnavalet, Paris, France/Archives Charmet/Bridgeman Images

My supplies, altogether voluntary, mostly confidential, often seeming quite providential, were numerous and varied. For instance, there were two distant and wealthy ladies, sisters, who sent regularly, for two years, quite heavy sums, enjoining that their names should be kept secret. The same delicacy was indeed a frequent condition. From several I had carte blanche. Many were entire strangers. From these sources, during from two to three years, in the manner described, in the hospitals, I bestowed, as almoner for others, many, many thousands of dollars. I learned one thing conclusively—that beneath all the ostensible greed and heartlessness of our times there is no end to the generous benevolence of men and women in the United States, when once sure of their object. Another thing became clear to me—while cash is not amiss to bring up the rear, tact and magnetic sympathy and unction are, and ever will be, sovereign still.

May 28–29, 1865

I stayed tonight a long time by the bedside of a new patient, a young Baltimorean, aged about nineteen years, (Second Md. Southern) very feeble, right leg amputated, can’t sleep hardly at all—has taken a great deal of morphine, which, as usual, is costing more than it comes to. Evidently very intelligent and well bred—very affectionate—held on to my hand, and put it by his face, not willing to let me leave. As I was lingering, soothing him in his pain, he says to me suddenly, “I hardly think you know who I am—I don’t wish to impose upon you—I am a rebel soldier.” I said I did not know that, but it made no difference…Visiting him daily for about two weeks after that, while he lived (death had marked him, and he was quite alone), I loved him much, always kissed him, and he did me.

In an adjoining ward I found his brother, an officer of rank, a Union soldier, a brave and religious man (Col. Clifton K. Prentiss, Sixth Md. Infantry, Sixth Corps, wounded in one of the engagements at Petersburg, April 2—lingered, suffered much, died in Brooklyn, August 20, 1865). It was in the same battle both were hit. One was a strong Unionist, the other Secesh; both fought on their respective sides, both badly wounded, and both brought together here after absence of four years. Each died for his cause.

June 9–10

I have been sitting late tonight by the bedside of a wounded captain, a friend of mine, lying with a painful fracture of left leg in one of the hospitals, in a large ward partially vacant. The lights were put out, all but a little candle, far from where I sat. The full moon shone in through the windows, making long, slanting, silvery patches on the floor. All was still, my friend too was silent, but could not sleep; so I sat there by him, slowly wafting the fan, and occupied with the musings that arose out of the scene, the long shadowy ward, the beautiful ghostly moonlight on the floor, the white beds, here and there an occupant with huddle form, the bedclothes thrown off.

Unfortunately, humanitarianism has been the mark of an inhuman time.

—G.K. Chesterton, 1932October 3

There are only two army hospitals now remaining. I went to the largest of these (Douglas) and spent the afternoon and evening. There are many sad cases, some old wounds, some of incurable sickness, and some of the wounded from the March and April battles before Richmond…Few realize how sharp and bloody those closing battles were. Our men exposed themselves more than usual; pressed ahead, without urging. Then the Southerners fought with extra desperation. Both sides knew that with the successful chasing of the rebel cabal from Richmond, and the occupation of that city by the national troops, the game was up. The dead and wounded were unusually many…Of the wounded, both our own and the rebel, the last lingering driblets have been brought to hospital here. I find many rebel wounded here, and have been extra busy today tending to the worst cases of them with the rest.

Three Years Summed Up

During my past three years in hospital, camp or field, I made over six hundred visits or tours, and went, as I estimate, among from eighty to a hundred thousand of the wounded and sick, as sustainer of spirit and body in some degree, in time of need. These visits varied from an hour or two, to all day or night; for with dear or critical cases I always watched all night. Sometimes I took up my quarters in the hospital, and slept or watched there several nights in succession. Those three years I consider the greatest privilege and satisfaction (with all their feverish excitements and physical deprivations and lamentable sights) and, of course, the most profound lesson and reminiscence of my life. I can say that in my ministerings I comprehended all, whoever came in my way, Northern or Southern, and slighted none. It afforded me, too, the perusal of those subtlest, rarest, divinest volumes of humanity, laid bare in its inmost recesses, and of actual life and death, better than the finest, most labored narratives, histories, poems in the libraries. It aroused and brought out and decided undreamed-of depths of emotion.

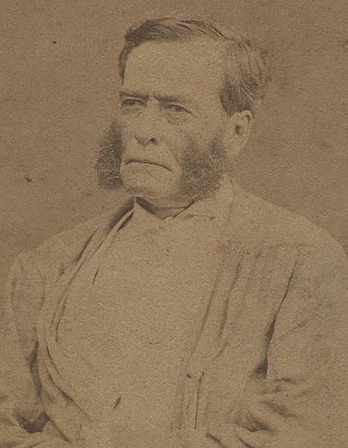

Walt Whitman

From Memoranda During the War. In 1862 Whitman left his bohemian life in New York to search for his brother George, a Union soldier whose name he had read in a list of casualties; he feared the worst but found him in Falmouth, Virginia, nursing only a wounded cheek. Whitman decided to offer his services in field hospitals and to document some of the war’s “interior history,” writing to Ralph Waldo Emerson in 1863, “This thing I will record—it belongs to the time, and to all the states—(and perhaps it belongs to me).”