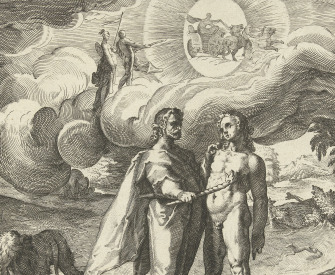

Messenger: Pentheus, king of Thebes,

I come from Cithaeron where the gleaming flakes of snow

fall on and on forever—

Pentheus: Get to the point.

What is your message, man?

Messenger: Sir, I have seen

the holy Maenads, the women who ran barefoot

and crazy from the city, and I wanted to report

to you and Thebes what weird fantastic things,

what miracles and more than miracles,

these women do. But may I speak freely

in my own way and words, or make it short?

I fear the harsh impatience of your nature, sire,

too kingly and too quick to anger.

Pentheus: Speak freely.

You have my promise: I shall not punish you.

Displeasure with a man who speaks the truth is wrong.

However, the more terrible this tale of yours,

that much more terrible will be the punishment

I impose upon that man who taught our womenfolk

this strange new magic.

Messenger: About that hour

when the sun lets loose its light to warm the earth,

our grazing herds of cows had just begun to climb

the path along the mountain ridge. Suddenly

I saw three companies of dancing women,

one led by Autonoë, the second captained

by your mother, Agave, while Ino led the third.

There they lay in the deep sleep of exhaustion,

some resting on boughs of fir, others sleeping

where they fell, here and there among the oak leaves—

but all modestly and soberly, not, as you think,

drunk with wine, nor wandering, led astray

by the music of the flute, to hunt their Aphrodite

through the woods.

But your mother heard the lowing

of our horned herds, and springing to her feet,

gave a great cry to waken them from sleep.

And they, too, rubbing the bloom of soft sleep

from their eyes, rose up lightly and straight—

a lovely sight to see: all as one,

the old women and the young and the unmarried girls.

First they let their hair fall loose, down

over their shoulders, and those whose straps had slipped

fastened their skins of fawn with writhing snakes

that licked their cheeks. Breasts swollen with milk,

new mothers who had left their babies behind at home

nestled gazelles and young wolves in their arms,

suckling them. Then they crowned their hair with leaves,

ivy and oak and flowering bryony. One woman

struck her thyrsus against a rock and a fountain

of cool water came bubbling up. Another drove

her fennel in the ground, and where it struck the earth,

at the touch of god, a spring of wine poured out.

Those who wanted milk scratched at the soil

with bare fingers and the white milk came welling up.

Pure honey spurted, streaming, from their wands.

If you had been there and seen these wonders for yourself,

you would have gone down on your knees and prayed

to the god you now deny.

We cowherds and shepherds

gathered in small groups, wondering and arguing

among ourselves at these fantastic things,

the awful miracles those women did.

But then a city fellow with the knack of words

rose to his feet and said, “All you who live

upon the pastures of the mountain, what do you say?

Shall we earn a little favor with King Pentheus

by hunting his mother Agave out of the revels?”

Falling in with his suggestion, we withdrew

and set ourselves in ambush, hidden by the leaves

among the undergrowth. Then at a signal

all the Bacchae whirled their wands for the revels

to begin. With one voice they cried aloud,

“O Iacchus! Son of Zeus!” “O Bromius!” they cried

until the beasts and all the mountain seemed

wild with divinity. And when they ran,

everything ran with them.

It happened, however,

that Agave ran near the ambush where I lay

concealed. Leaping up, I tried to seize her,

but she gave a cry: “Hounds who run with me,

men are hunting us down! Follow, follow me!

Use your wands for weapons.”

At this we fled

and barely missed being torn to pieces by the women.

Unarmed, they swooped down upon the herds of cattle

grazing there on the green of the meadow. And then

you could have seen a single woman with bare hands

tear a fat calf, still bellowing with fright,

in two, while others clawed the heifers to pieces.

There were ribs and cloven hooves scattered everywhere,

and scraps smeared with blood hung from the fir trees.

And bulls, their raging fury gathered in their horns,

lowered their heads to charge, then fell, stumbling

to the earth, pulled down by hordes of women

and stripped of flesh and skin more quickly, sire,

than you could blink your royal eyes. Then,

carried up by their own speed, they flew like birds

across the spreading fields along Asopus’ stream

where most of all the ground is good for harvesting.

Like invaders they swooped on Hysiae

and on Erythrae in the foothills of Cithaeron.

Everything in sight they pillaged and destroyed.

They snatched the children from their homes. And when

they piled their plunder on their backs, it stayed in place,

untied. Nothing, neither bronze nor iron,

fell to the dark earth. Flames flickered

in their curls and did not burn them. Then the villagers,

furious at what the women did, took to arms.

And there, sire, was something terrible to see.

For the men’s spears were pointed and sharp, and yet

drew no blood, whereas the wands the women threw

inflicted wounds. And then the men ran,

routed by women! Some god, I say, was with them.

The Bacchae then returned where they had started,

by the springs the god had made, and washed their hands

while the snakes licked away the drops of blood

that dabbled their cheeks.

©1959 by the University of Chicago. Used with permission of the University of Chicago Press.

From The Bacchae. “Maenad” derives from the Greek word for “mad” or “demented”; the women were thought to be possessed by the god of wine who had the power to tear men into pieces, a fate suffered by Orpheus. The last of the great tragedians after Aeschylus and Sophocles, Euripides is known to have written ninety-two plays; only nineteen are extant. According to Plutarch, some Athenian prisoners held in the Syracusan quarries after the Sicilian expedition of 415 bc were given their freedom if they could recite passages of Euripides from memory.

Back to Issue