A man who exposes himself when he is intoxicated has not the art of getting drunk.

—Samuel Johnson, 1779Players Club

From Falstaff to Cassio, intoxication to addiction, a brief history of Shakespeare and alcohol.

By Rebecca Lemon

Falstaff with Pewter Jug and Wineglass, by Eduard von Grützner, early twentieth century.

On a June day in 1598, at about three o’clock in the afternoon, nearly three thousand patrons file into The Curtain, a London playhouse on the outskirts of the city, along the Shoreditch road. They wait for the actors of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men to take the stage for a hotly anticipated new play by William Shakespeare, the sequel to his enormously popular Henry IV. An instant hit in 1596 and one of the playwright’s most performed in the four hundred years following its premiere, the first part of Henry IV stages the history of England before the Wars of the Roses. King Henry IV struggles to hold on to his throne, in part because of political rebellion, but also because of concerns about his rogue son and heir, Prince Hal. While the play’s historical insights no doubt appealed to Shakespeare’s audience, the real reason for the play’s success lies with Sir John Falstaff, a “villainous, abominable misleader of youth” and Shakespeare’s best-loved comic creation. Falstaff, a portly, drunken knight, is corrupter of the young Prince Hal and hero of the play’s tavern underworld.

Known for his drunken antics, Falstaff eventually attracted as much scholarly attention as the solemn and tragic Hamlet. In the 1590s, though, his humor earned him royal, rather than scholarly, notice: Queen Elizabeth, captivated by the knight in Henry IV, Part 1, purportedly asked to see a play that showed Falstaff in love. Shakespeare spent the next year writing and producing The Merry Wives of Windsor to satisfy Her Majesty, delaying the appearance of a sequel to Henry IV. The wait has made this summer afternoon in 1598 all the sweeter. As the performance begins, the audience once again revels in Falstaff and the heir apparent avoiding the battlefield for the bar. In both plays, Hal initially shirks his princely duties to drink with Falstaff at his favorite haunt, the Boar’s Head Tavern. The audience relishes this cheeky rebellion, raising their pints in unison.

The character of Sir John Falstaff is the soul of wit, inspired by drink. As the long-awaited sequel draws to a close, rebels surround the king’s troops and Falstaff evades the fighting on a nearby battlefield, sucking on his flask instead. In one of the play’s last scenes, the abstemious and dutiful Prince John chides Falstaff for his drinking, and the knight responds with a famous soliloquy, his encomium to the dry (“sec”) white wine known as sack:

A good sherry sack hath a two-fold operation in it. It ascends me into the brain, dries me there all the foolish and dull and crudy vapors which environ it, makes it apprehensive, quick, forgetive, full of nimble, fiery, and delectable shapes, which, delivered o’er to the voice, the tongue, which is the birth, becomes excellent wit.

Wine, in short, produces wit, and as Falstaff goes on to argue, courage as well—sack lights up the face like a bright-red beacon, warning the drinker to arm himself to fight. Falstaff argues so strongly for the benefits of intoxication that he ends the speech declaring, “If I had a thousand sons, the first human principle I would teach them should be to forswear thin potations and to addict themselves to sack.”

With tankards in hand, the audience members watch Falstaff. Packed into the open-air theater, they are simultaneously enrapt by Shakespeare’s wit and diverted by the drinks and snacks on offer. While Falstaff tucks into his tavern fare—his famous bar bill in Henry IV, Part 1 included bread, anchovies, capon (a castrated rooster dish popular with Elizabethans), and two gallons of sack—the audience enjoys a feast of oysters, crabs, mussels, periwinkles, and cockles; some nibble on walnuts, hazelnuts, plums, cherries, peaches, dried raisins, or figs.

The Headache, by George Cruikshank, c. 1830.

But more than snacking, this audience joins Falstaff in drinking heavily, ordering up their ale and wine straight through the performance and the intermission. All playhouses have liquor on-site, and The Curtain is no exception. As Thomas Platter, a Swiss visitor to London, noted in his diary in 1599, “During the performance food and drink are carried round the audience, so that for what one cares to pay one may also have refreshment.” The distractions were many, not only from drunk patrons themselves: ale produced a hissing noise when tapped, and those opening it were shouted down by audience members annoyed by the sound.

After the performance, fresh from hearing Falstaff’s advice to “addict themselves to sack,” the audience members, as well as the actors and playwrights, head to one of the taverns or inns scattered throughout Shoreditch or lining London’s Bankside. Even if in 1598 the actors could boast an engagement at a permanent theater such as The Curtain, they still remember inn yards, the sites of their first performances—ale and theater have always been yoked together in the history of English playing. Tripping past the Puritans railing against their art, actors and their devoted audiences file into the Mermaid, the Devil, the Falcon, or perhaps even the Boar’s Head itself, an actual establishment in Eastcheap near the playhouse where Shakespeare had Falstaff run up his bar bill.

Settling in with a glass of wine or a tankard of ale, the wealthy and middling sort of patrons enjoy community and poetic inspiration at the tavern. Less-well-to-do patrons—including the porters, apprentices, servingmen, and the prostitutes who attempted to engage them—head to an unlicensed alehouse, visible by not a sign but a broom outside or a red lattice painted on the wall. Here the oft-derided alewife—a profession declaimed by poets as “scurvy” and “lowsy,” diseased and lice-infested—might cut short measures or serve stale home-brew. But despite such detractions, the alehouse offers cheaper drinks and freedom from the sack-drinking elite packing the tavern or inn. Since one’s choice of beverage helped to signify one’s class status, drink functioned as a mode of recognition. Elite poets could unite in their consumption of sack while the groundlings enjoyed the poorer beverages of ale or beer. If Falstaff spent five shillings and eight pence on his two gallons of sack at the Boar’s Head Tavern—more than $140 in today’s dollars—the actor who played him, who earned a shilling a day ($25), might instead opt for two-thirds of a gallon of beer for a penny ($2) at the nearby alehouse.

Gathered around cups or tankards, the theater’s increasingly intoxicated patrons debate well into the night the two-hours’ traffic of the stage. Justices of the Peace were meant to regulate “inordinate haunting and tippling” of inns and alehouses and could fine patrons who lingered for too long: three to four shillings for a first offense ($75 to $100); this was nearly a week’s wages for an actor and would be a steep fee for most folks. Any tavern haunter unable to pay the fine would be set in the stocks. But more likely, some eager patrons might ignore such social conventions and the threats of the magistrates (who themselves were just as likely to be drinking as arresting other patrons). It is, after all, more pleasurable to follow the example of Falstaff, who haunts his beloved tavern at every opportunity.

Elevated and inspired, these men participate in a carnivalesque world, turning the established order on its head—the impoverished drinkers become kings for a day. The tavern patrons raise a glass to the errant, earthy, and appetitive Sir John Falstaff, their hero and muse: “Banish plump Jack, and banish all the world.”

William Shakespeare knew the delights of the tavern well. Ben Jonson’s gathering at the Mermaid was a fraternal union of drink, pleasure, and convivial conversation; the tavern was a place where Shakespeare and Jonson could exchange barbs and jests, fueling their friendship and theatrical rivalry. Here the Bard honed his craft, and fantasies prompted by intoxication could flourish into art; drunken delirium offered Elysium, and illusion turned to Illyria, the setting of one of Shakespeare’s most famous comedies, Twelfth Night.

Shakespeare didn’t just enjoy the interplay of drinking, fantasy, and theater at his favorite taverns, he also enacted this productive relationship onstage. Shakespeare began his popular comedy The Taming of the Shrew with a curious framing device, one that bears little relation to the famous barbs of the lovers’ plot. The play opens with the drunken tinker Christopher Sly arguing with a tavern hostess. He has broken beer glasses and refuses to pay. As she heads to fetch the constable, Sly falls into a stupor; upon waking, he finds himself dressed and pampered as a nobleman. This transformation has occured because a passing Lord, who stopped at the tavern for refreshment, saw the drunken Sly and came up with a plan for his own amusement: he would take the tinker to his “fairest chamber” to be pampered with “wanton pictures” and “rose water.” Sly then struggles comically to adjust to his dramatically changed circumstances. The prologue ends as the Lord insists that Sly enjoy himself and take in a play.

Sly’s transformation initially is alarming; but ultimately it brings to life the fantasy of a downtrodden Elizabethan. First encountering his new aristocratic surroundings, Sly demands, “For God’s sake, a pot of small ale,” but a servant counsels a more class-appropriate beverage: “Will’t please your lordship drink a cup of sack?” Unnerved by his dramatic metamorphosis, the tinker responds: “I am Christopher Sly. Call me not ‘honor’ nor ‘lordship.’ I ne’er drank sack in my life.” The servants insist he is noble, causing Sly to ask:

What, would you make me mad? Am not I Christopher Sly—old Sly’s son of Burton Heath, by birth a pedlar, by education a cardmaker, by transmutation a bearheard, and now by present profession a tinker? Ask Marian Hacket, the fat alewife of Wincot, if she know me not. If she say I am not fourteen pence on the score for sheer ale, score me up for the lying’st knave in Christendom.

Sly’s speech perfectly rehearses drinking rituals of Elizabethan life. Trying to make ends meet during a time of poverty, famine, and plague, Sly was born poor and moves from job to job: he makes metal combs, he tames bears, and now he mends pots. He spends what little money he earns in the tavern, seeking escape. In tight times, he relies on the alewife to supply him beer on credit; she marks his debts on the chalk tally called a score and may, like the hostess who opens the play, need to call the constable to force him to pay up.

In Shakespeare’s plays, alcohol doesn’t merely comfort the poor, it transforms them, and nowhere is the transformative power of alcohol more profound than in the case of Christopher Sly. He opens the play in snarling prose, demanding beer and escaping the law, but as he comes to terms with his newly acquired aristocratic status he begins to speak in lyrical verse. Believing the three servingmen who tell him of his glorious estate and his beautiful wife, he asks,

Am I a lord, and have I such a lady?

Or do I dream? Or have I dreamed till now?

I do not sleep. I see, I hear, I speak.

I smell sweet savors, and I feel soft things.

Upon my life, I am a lord indeed,

And not a tinker, nor Christopher Sly.

Well, bring our lady hither to our sight,

And once again a pot o’ th’ smallest ale.

The crowning moment of this scene of luxury comes when a troop of players enter, offering “a pleasant comedy” prescribed by doctors to cure melancholy: “They thought it good you hear a play/And frame your mind to mirth and merriment,/Which bars a thousand harms and lengthens life.” By advertising the benefits of not only alcohol but of theater itself, Shakespeare suggests this audience will receive the kind of transformative experience offered to Sly for a fraction of the cost; even those who pay a penny to stand in the yard will experience “mirth and merriment,” transported from “a thousand harms” toward a longer life. Social climbing might prove impossible for most theatergoers, but in the tavern and on the stage one might set one’s worries aside and dream, if only for a little while. As Christopher Sly proclaims when settling in to watch the play within a play, “Well, we’ll see’t. Come, madam wife, sit by my side/And let the world slip. We shall ne’er be younger.”

In the end, Sly’s drunken dream is fleeting. From the moment he is addressed as a nobleman, the audience realizes that Sly is the butt of a joke played by the Lord. On seeing Sly asleep in his drunkenness, the Lord berates him, “O monstrous beast! How like a swine he lies./Grim death, how foul and loathsome is thine image.” The Lord views Sly as no more than an animal, one he might “practice” or play a trick on, and such a joke would be, he declaries, “a flatt’ring dream or worthless fancy.” The change will be insubstantial; like Prospero’s pageant, it will fade to airy nothing. Once The Taming of the Shrew proper begins, after this opening prologue, Christopher Sly appears again only briefly: he interjects, as the first scene unfolds, that the play “’Tis a very excellent piece of work, madam lady/Would ’twere done.” This ambivalent statement proves his last, and the audience neither hears from nor sees him again; the tinker turned nobleman slinks back into the anonymous mass of tipplers who haunt London society.

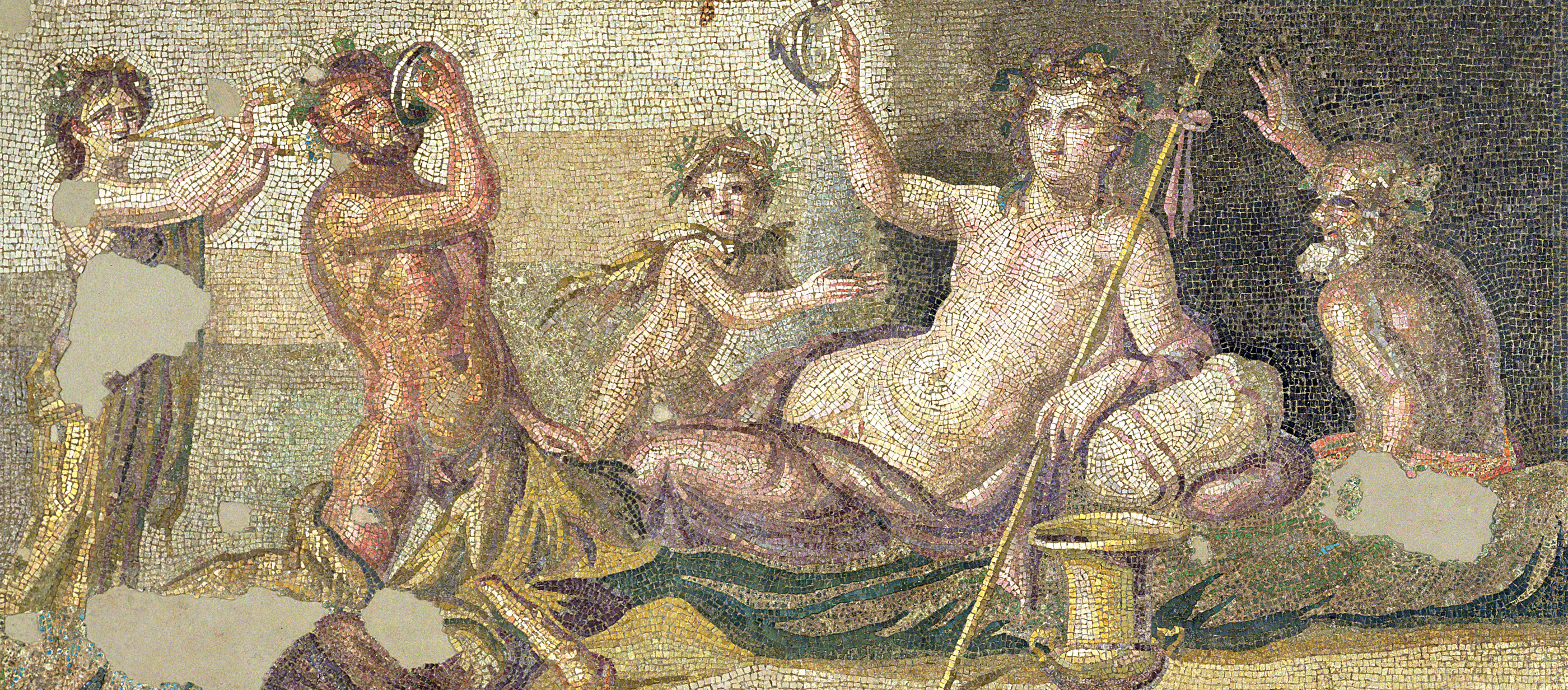

Drinking contest between Dionysos and Heracles, mosaic, Antioch, c. 100.

Even though its effects were temporary, drinking offered a much-needed form of escape from the myriad of difficulties facing early modern audiences, at a time when poverty, sickness, disaster, and sudden death were prominent features of life. An outbreak of the plague in London in 1592 led to the closing of the theaters and nearly seventeen thousand deaths. The average life expectancy at the beginning of the seventeenth century was thirty-six years, and around 10 percent of infants died in their first year of life. Childbirth accounted for nearly 20 percent of deaths for women between the ages of twenty-five and thirty-four. Smallpox and typhus were especially deadly; poor water and unsanitary food-preparation led to dysentery and salmonella. Famine came with grain shortages and inadequate distribution of food. Finally the pox, namely, syphilis and other venereal diseases, caused acute pain (“bone ache”), disfigurement, and eventual death. In managing the emotional and physical pains brought on by diseases and epidemics, alcohol proved an essential narcotic. It was an anesthesia available to all and especially valuable to the very poor.

Patients might turn to apothecaries for some relief from “bone ache” or other infirmities; there were as many as 150 apothecaries in London in Shakespeare’s day, and they supplemented the work of more expensive university-trained physicians by offering diagnoses and potential cures. A visit to a physician could run anywhere from ten shillings ($250) to a pound ($500), while a trip to the apothecary was considerably cheaper, as with a visit to the pharmacist today. Apothecaries worked out of storefronts much like those of modern drugstores, and their ailing customers might watch the mixing of medicines. These early modern druggists offered products made with herbs, plants, and roots, but also with exotic substances ranging from gold to opium. One could purchase a pound of opium for twelve shillings ($300); rose water ran sixteen pence a pint ($32); minerals and stones, including topaz and sapphire, might be purchased for around twelve shillings ($300) per pound. Other medicines included moss, smoked horse testicle, May dew, and henbane.

But these drugs could be unreliable and dangerous, as Romeo acknowledges when he approaches an impoverished apothecary, while carrying a small fortune to pay for the fatal poison that he will use to kill himself:

Come hither, man. I see that thou art poor.

Hold, there is forty ducats. Let me have

A dram of poison—such soon-speeding gear

As will disperse itself through all the veins,

That the life-weary taker may fall dead,

And that the trunk may be discharged of

breath

To this the apothecary responds, “Such mortal drugs I have, but Mantua’s law/Is death to any he that utters them.” Need of money, of course, overcomes the apothecary’s hesitation, and he sells the fatal draught to Romeo.

In the dark and crowded streets of London, any draught could be fatal. If an ale lover or mummy sipper tippled into the path of a wagon on Cheapside they would be headed straight into Satan’s pocket, at least according to the exasperated shouts of godly Puritans lining the street who railed against lechery, swearing, and drinking; they also condemned the theater and alehouse as ground zero for the Antichrist. Thanks to the efforts of the Puritans, intoxication was a two-faced creature: elevation by the spirit of God and grace was acceptable and often ecstatic; elevation by other spirits was questionable and likely evil. The Puritans undertook what historians have called a reformation of manners, attempting to corral unruly audiences at theaters, patrons at taverns, and other populations away from dens of iniquity into the joys of Sunday worship. (The Puritan threats of hellfire and damnation seemed to come true on June 29, 1613: the Globe Theater went up in flames when wadded paper from a cannon shot during a performance of Henry VIII hit the theater’s thatched room and started a raging fire. Perhaps to the chagrin of the godly, a bottle of ale saved one man, who doused his burning trousers with his drink.)

A reliance on drink worried Puritans deeply. If one might be transported to rapture by drink and theater, one might be transported in the other direction: toward hell and the beasts within. Gods Judgements upon Drunkards, Swearers, and Sabbath-Breakers (1659) was a book that offered forty-seven pages on the horrors of drunkenness, with many specific examples of drunkards who stabbed themselves, fell off horses, drowned to death, or stumbled only to die in ditches. “Excessive drinking,” Thomas Beard cautions in The Theatre of Gods Judgements (1597), “is one principal cause why men are now so short lived.” The intoxicating power of drinking is akin to that of a magical charm or potion:

Drunkards, being the devil’s deputies to turn others into beasts, will make themselves devils, wherein they have a notable dexterity; making the alehouse or tavern their study; their circle, the pot; themselves, the conjurers; men’s souls, the hire; reputation of good fellowship, the charm; the characters, healths.

Like the Lord who deems Sly a monstrous beast, The Odious, Despicable, and Dreadfull Condition of a Drunkard (1649) decries the drinker as “half a man, half a beast; or one that was born a man, lives a beast; or one that hath a beastial heart in a case of human flesh.” As for the theater, playing brought too much “pleasure, sloth, sleep, sin, and without repentance to death and the Devil.” Moralizing concerns about the theater at the end of the sixteenth century, like those attacks on the National Endowment for the Arts at the end of the twentieth, exposed conservative fear of the power of art. The permanent London theater was a new phenomenon, one that had not been fully digested into the culture and whose spectacles still had the power to overwhelm and shock. When Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, intoxicated by magic, summons the devil onstage, does he teach the audience how to do the same? Faustus enjoys twenty-four years of luxury before hurtling to hell in the play’s last moments; perhaps some audience members might find this a fair bargain. When theater patrons hear Falstaff trumpeting the joys of sack, might they raise a glass in solidarity, running from Sunday sermons to the alehouse instead?

The Headache, by George Cruikshank, c. 1830.

The danger, then, isn’t simply that the audience watched an intoxicating spectacle; it was that they became intoxicated themselves. Thus theatrical spectacle works as a kind of drug, transforming the viewer both mentally and physically—the round theater embraces them as part of the event, leaving them forever changed.

In the final scenes of Henry IV, Part II, when Falstaff, avoiding the battlefield, counsels his imaginary sons “to addict themselves to sack,” the audience can plainly see that his health has deteriorated over the course of the two plays and that sack is offered up as a last effort at a better life, a pleasing beverage that might solve all ailments.

Throughout Henry IV, Falstaff has been described—in comic yet telling terms—as a “bolting hutch of beastliness,” a “stuffed cloak bag of guts,” a “swollen parcel of dropsies,” a “huge bombard of sack”; his ailments include being “fat kidneyed,” “short winded,” and “rheumatic”; one who “sweats to death,” suffers from “diseases” and an incurable “consumption of the purse.” At the end of Part I, Falstaff had sworn off sack: “I’ll purge, and leave sack, and live cleanly, as a nobleman should do,” but his attempt at reform is short lived. As the doctor’s page at the start of Part II claims, Falstaff’s “water itself was a good healthy water, but, for the party that owed it, he might have more diseases than he knew for.” Falstaff’s “cloak bag of guts” might have caused the audience to howl with laughter, but early modern pamphleteers chronicled a precise link between intoxication and infirmity. In A Looking Glasse for Drunkards (1627), the author describes how drunkenness creates “multitudes of diseases in the body of man, as apoplexies, falling sicknesses, palsies, dropsies, consumptions, giddines of the head, inflammation of the blood and liver.” These diseases plague Falstaff. Henry IV ends not with Falstaff leaving drink, then, but instead promoting addiction. Part I concludes with hope for Falstaff, Part II with despair and habitual drunkenness.

In the final scene of Henry IV, Prince Hal is now King Henry V. Hearing of Hal’s ascension to the throne, Falstaff initially celebrates, imagining that England will now be a carnival with no rules or regulations. He hurries to London, shouting out as the new king passes by on his coronation march. But King Henry V turns to Falstaff and delivers a chilling speech to his old friend,

I know thee not, old man. Fall to thy prayers.

How ill white hairs become a fool and jester!

I have long dreamt of such a kind of man,

So surfeit-swelled, so old, and so profane;

But being awaked, I do despise my dream.

Make less thy body hence, and more thy grace.

Leave gormandizing; know the grave doth gape

For thee thrice wider than for other men.

Henry banishes Falstaff from his company, deeming his addiction to sack neither comical nor inspired; their once bosom friendship is now poisoned.

The hopes and fears about intoxication staged in Henry IV stress the bifurcated nature of the word: at its root, intoxication (in-toxicare) means to ingest toxic, physically altering substances. Shakespeare often registers these double meanings of intoxication in his plays—as poison and cure, as a toxin and a pleasure. Intoxication might indeed lead, as suggested in Taming of the Shrew and Henry IV, to theatrical inspiration. But more often, intoxication is associated with poison, disease, and treason.

In Othello a crucial turn of the plot depends upon the solider Cassio’s intoxication: thanks to the lieutenant’s drunkenness, Iago is free to snare the title character with his poisonous lies. Cassio laments being dismissed for drunkenness, but refuses to approach Othello, saying:

I will ask him for my place again. He shall tell me I am a drunkard. Had I as many mouths as Hydra, such an answer would stop them all. To be now a sensible man, by and by a fool, and presently a beast! O, strange! Every inordinate cup is unblessed, and the ingredient is a devil.

Cassio echoes Puritan pamphleteers: a drunkard is a beast, and drink a devil. Iago calls Cassio’s drinking an “infirmity” and Montano agrees, “And ’tis a great pity that the noble Moor/should hazard such a place as his own second/With one of an engraffed infirmity.” While Iago tricked Cassio and slandered him as a habitual drunkard, nevertheless the play hinges on the lieutenant’s weakness for drinking and thus teaches the audience the dangers of such intoxication. It transports Cassio away from merriment toward condemnation, a sobering spectacle for a heavy-drinking audience.

In Hamlet Claudius also uses drink as a weapon: the play ends with a poisoned cup of wine, prepared by the king for Hamlet but mistakenly and fatally ingested by Queen Gertrude. If drinking kills characters in Hamlet, even the most comic scenes of Macbeth and The Tempest mingle drunken characters with treason and death: the Porter pitches the joys of inebriation as the Macbeths clean their hands of the king’s blood; Stefano and Trinculo guzzle a keg and plot to kill Prospero. The love potion in Romeo and Juliet kills rather than cures. Cleopatra hides away her own special draught to facilitate suicide; Antony gets drunk on a barge. Draughts and potions—these substances produce scenes of intoxication tainted by dark desires and threats of death. Even as Shakespeare created uplifting portraits of the “merry” drunkard, he equally illuminated what was clear to the Puritan: addiction was a growing problem in early modern England.

The scientific story of addiction wasn’t developed until the early nineteenth century, when two pioneering physicians—Founding Father Benjamin Rush in America and Thomas Trotter in Scotland—performed the first studies of alcoholism. But the problem of addiction already had begun to emerge by the turn of the seventeenth century, as Shakespeare’s audience, watching Henry IV, was no doubt keenly aware. The dangers of intoxication, palpable in 1598, would only increase over the next two hundred years. The high offered by beer and wine, while significant, would pale in comparison to the stupor brought on by harder substances.

Head of Dionysos, terracotta sculpture, ancient Gandhara region, Pakistan, c. 400. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Uzi Zucker, 1979.

Gin drinking exploded at the end of the seventeenth century when a politically motivated embargo on French brandy led William of Orange to encourage the distillation of spirits instead. The much higher alcohol content of gin, nicknamed “mother’s ruin,” produced an epidemic of excessive drunkenness, leading to five new acts passed by parliament in response to the gin craze of the 1720s and 1730s. William Hogarth’s Gin Lane features gin drinkers, a stupified bunch compared to the cheerful drinkers of Beer Street.

From 1830 on, opium became more available in England, through trade with India. Opium eaters consumed larger and more potent quantities of the intoxicant. A series of physicians trumpeted the drug’s curative powers, only later discovering the dangers of addiction. Opium had been available in the form of laudanum through the medieval and early modern periods, but after trade with China in the 1860s introduced the practice of smoking it, that became the primary method in England. Doped on gin and opium, the drinker and smoker were no longer elevated into sociability and wit; they were pulled into antisocial behavior. Gin drinkers were accused of abandoning their families to fight in the streets; the grain provoked violence. Opium eaters burrowed into dens, sleepily oblivious to the world around them. Intoxication had tipped into addiction.

Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, the merry intoxicant migrated from the Elizabethan alehouse to the Victorian opium den; from a daytime gathering of thousands in an open theater, cheering the wit of their favorite players, to a solitary chamber in the dead of night. Shakespeare’s fairy-tale fantasies of wealth, love, and happiness transformed into fever dreams, typified by Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem “Kubla Khan." As Coleridge recounts in the preface to the poem, after taking an anodyne of opium, he fell into a feverish hallucination; upon awaking from his dream, he vaguely recalled his poem, composed while asleep, but lost once interrupted: “All the rest had passed away like the images on the surface of a stream into which a stone had been cast.” The writer no longer haunts the taverns of the Bankside, surrounded by the men who enact his characters and the audiences who love them. Shakespeare’s beer drinker turns into Coleridge’s opium eater, intoxication becomes addiction. Falstaff’s advice to his imaginary sons—“to addict themselves to sack”—is a tantalizing remnant of a merrier, theatrical time, and an astute warning about the isolating dangers to come.