One should either be a work of art, or wear a work of art.

—Oscar Wilde, 1894When Women Ruled Fashion

In the late seventeenth century, haute couture was produced by women, for women.

By Joan DeJean

The Empress Eugénie Surrounded by Her Ladies-in-Waiting, by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, 1855. © Château de Compiègne, Oise, France/Bridgeman Images.

As the story is usually now told, Charles Frederick Worth (1825–1895), often described as a French couturier of British origin, created the institution of haute couture. This take on fashion history defines the most respected sector of the fashion world—the sector where the economic stakes are highest—as having always been what it largely is today: a male preserve.

It’s true that, despite such notable exceptions as Coco Chanel, beginning with the founding of the Maison Worth in 1858, the great fashion houses have been run by men. From today’s vantage point, it seems as if it’s always been the same scenario: men designing women’s clothing and dictating not only color and skirt length but the ideal shape for the female body—even the types of undergarments to be used to achieve perfect proportions.

But the history of haute couture is more than an all too predictable chronicle of famous tailors. At a crucial origin of the modern fashion industry, at the moment when individuals first became willing to travel long distances to have their clothing made by a designer with an international reputation, couture was neither exclusively nor even primarily a man’s game. It could be argued that fashion became an industry in large part because female designers decided it was time to take a leading role in the production of high-fashion garments. At that founding moment, couturières rather than couturiers dictated the rules of fashion.

Today, to the extent to which the fashion industry is regulated, the process is managed principally by multinational luxury-goods conglomerates that control many of the most prestigious fashion houses, and to some extent by national professional organizations such as the Council of Fashion Designers of America and the Fédération Française de la Couture. Prior to the French Revolution, the right to produce luxury garments was far more tightly controlled: each European country had a guild system; to make garments for the rich, it was necessary to be accepted into a prominent guild. In England men vied for admission to the Merchant Tailors Company; in France they sought positions as maîtres tailleurs, master tailors. These tailors worked for an elite and tiny clientele of nobles, who followed the fashions of the day. When Louis XIV appeared in a striking new outfit, for example, master tailors were sure to be asked to create a line-by-line copy.

In order to maintain the economic value of an appointment as master tailor, guild leaders controlled the number of positions. As part of this effort, for centuries, guilds in all countries fought off any attempt by women to win access to the highest ranks of fashion design. Officially, there were only tailors—and never seamstresses.

Autumn Zephyr, by Catherine Abel, 2001. © Private Collection / Bridgeman Images.

Then, in Paris in 1675, centuries of established practice were reversed. At Versailles on March 30, Louis XIV signed the statutes that created a new guild: the Corporation of the Maîtresses Couturières, or Mistress Seamstresses, a title that marked the official entrance of the vocabulary of couture onto the scene of high fashion. The corporation given legal status by these statutes was part of a rare development: a vast expansion of the French guild system spearheaded by Louis XIV’s chief economic adviser, Jean-Baptiste Colbert. In 1672, just before Colbert began his work, there were 60 trade corporations in Paris. By 1690, the number had more than doubled, to 129. Of that total, only five guilds and only two of the newly created guilds were reserved for women. (The second new trade organization gave legal status to a far less lucrative profession than the garment trade, the maîtresses bouquetières, women allowed to make and sell bouquets of fresh flowers in prominent locations such as the Pont Neuf.)

But the significance of the couturières’ association went beyond the role it afforded the female artisans who became its founding members. Their guild ushered in what was arguably women’s greatest moment of influence on the scene of high fashion—and the couturières’ influence was not limited to France but was soon felt all over Europe. Because of the combination of the seamstresses’ technical and commercial savvy, the unflagging support of their large and loyal clientele, and a measure of good luck, before the decade was out, a new age had begun for womenswear. Women dressing women in a manner that responded directly to those women’s desires and needs: this simple formula turned the fashion world inside out.

The opening couldn’t have come at a more opportune time: in the course of the next two decades, French high fashion began to reach a vastly expanded market. Foreign visitors were arriving in Paris in great numbers; they wanted to return home with garments in the latest French style. At the same time, the French market was growing rapidly, as more nonaristocrats acquired the means to live as nobles did. And a new, more public kind of shopping began, when tailors and shoemakers and hairdressers opened boutiques near the Louvre and such prime tourist destinations as the Tuileries gardens.

Women had long marketed their needlework skills—the new guild statutes openly acknowledge the fact that because many women “of all ranks” preferred to have their clothing made by seamstresses, female professionals were already working in the garment trade. A handful of them had even managed to secure positions at court by being named the official couturière of a queen or the wife of an heir to the throne. But until 1675 women’s participation in the guild system had never been legally authorized, which confined them to the trade’s lower echelons: they produced basic garments for a less elite clientele; they redesigned garments for secondhand sale. Their work had also often been dangerous. Many of the best-paying jobs were outsourced by tailors. Yet when women tried to collect their fees, police records show that sometimes rather than payment seamstresses received a beating.

Guild status afforded these women new legal protection. Tailors were ordered to cease the methods they had been using to put their female rivals out of business: the statutes speak of “raids” on seamstresses’ workshops, “seizures” of their goods, and “fines” imposed on them for illegal work.

In addition, since clandestine workshops lacked the resources necessary to produce true luxury garments, official status also made the couturières’ work far more lucrative. The statutes divided high fashion into two segments: one the preserve of tailors, the other controlled by couturières. The royal proclamation made it possible to establish what were in essence the first maisons de couture run by women.

And there were seamstresses, twenty-four of them to be precise, who were waiting for the chance to do just this. The thick register that contains seventeenth-century records of all Parisian guilds is today housed in the French National Archives of Paris, where I came across the first signs of the new guild’s life. Barely a month after the royal proclamation, on May 2, 1675, an entry in that register records that the new corporation had admitted its founding cohort. Marie Desprast became the first woman to sign the guild record books as a maîtresse couturière, the first woman to attain official status in the world of high fashion.

In late July five more couturières gained admission; by the end of 1675, 46 seamstresses had won the legal right to practice their trade. By the end of 1676, 99 female high-fashion professionals were officially active in Paris. When they met to elect guild officials in June 1680, 75 seamstresses showed up to vote. Even though the fledgling guild was only about a third as large as the mightiest fashion corporations, such as those of hat makers and embroiderers, it was already slightly larger than guilds such as the gainiers, who produced small leather goods.

It’s hard to know why the French state chose to give women this prominent status in the highest end of the garment trade in 1675. The royal decree offers but one justification for such a major reorganization of the French fashion scene: the king had “taken into account” the fact that “the decency and the modesty of women and young girls made it appropriate to allow them to have their clothing made by persons of the same sex.” At a moment when they were eager to expand the luxury-goods industry, the Sun King and his hard-nosed financial adviser explained their decision to take on that powerful economic motor, the guild system, in terms that had nothing to do with finance: they were simply making it possible for women to feel at ease when they chose high-fashion garments.

But the rest of the lengthy document tackles head-on the economic stakes of such a move in terms that seem designed to pacify master tailors. The seamstresses’ territory was carefully limited: women were not allowed to make garments for men, or even for boys over the age of eight. They were also excluded from the most lucrative sector of women’s wear: the most intricate, elaborate, and expensive garments then made, the outfits owned by women who frequented the court. According to their founding statutes, maîtresses couturières could make only habits de commodité, comfortable or casual dress.

The tailors could have been seen as having come away with the biggest prizes. Not only had they retained total control over men’s wardrobes—and this in the kind of age that just may be dawning again, when a man’s high-fashion outfit was every bit as elaborate and expensive as a woman’s and when men were just as avid consumers of high fashion as women. Tailors also had kept complete rights to what the statutes refer to as “robes.”

In French today the word robe refers to that basic staple of a woman’s wardrobe, a one-piece dress. But in seventeenth-century terms, robe designated the robe de cour, court dress, a two-piece affair composed of bodice and skirt. In court dress, the bodice was elaborately boned and painstakingly fitted to a woman’s body so that her torso would be tightly bound in. Such labor-intensive and technically demanding work guaranteed that the bodice was among the most expensive items in a noblewoman’s wardrobe. In addition, since robes were obligatory dress for all court occasions and for all formal visits, they also featured the most expensive fabrics and richest ornamentation, factors that drove up their price still more.

But if master tailors were reassured by any of this, that feeling was short-lived.

A few years later, the tide had turned completely in the couturières’ favor. Robes were on their way out, and the more casual styles that were the exclusive preserve of the new female guild were carrying the day. The kind of phenomenon much talked about but only rarely encountered in the world of style had begun: a true fashion revolution. The radical change of the 1670s was comparable to the 1920s, when under the impetus of American female designers, sportswear, a ready-to-wear look comprising combined separates, captured the imagination of female clients all over the globe.

Both these fashion phenomena, the informal dress of the 1670s as much as sportswear, were created by designers and for clients expressly seeking to turn away from the stiff look that dominated high fashion at the time of their creation. Both sought to cater to a new lifestyle among contemporary women: more active and more casual. In both cases, the new look offered an alternative to the tightly fitted and constraining fashions imagined by male designers. It was still high fashion, but couture on a different wavelength. During both these fashion revolutions, luxurious practicality was the order of the day.

And in both cases, the new casual look made outfits that only a few years earlier had been the height of elegance seem old-fashioned and stuffy. In 1675 the robe with which the master tailors were rewarded would have been seen as the ne plus ultra in luxury fashion. But by 1678 the robe was no longer fashion, that is, a style that changed and evolved with the seasons and the needs and whims of consumers. It was becoming instead a frozen, timeless entity. The robe continued for decades to be required dress for women at court. But over time it survived increasingly as a relic, a faded reminder of the glory days of Versailles during Louis XIV’s reign. And during all those decades, it was the object of growing hatred on the part of women of the court, who prided themselves on owning as few robes as possible and on wearing them as seldom as they could.

The casual dress that the 1675 statutes handed over to couturières continued to change and morph, both in France and all over the continent. Compared with the tight precision of court dress, the casual look of the 1670s was a breeze to fit and alter; it could be handily adapted to different occasions and suited to different looks.

It is also the first high-fashion style to have been extensively documented at the time of its creation—and this is where the couturières got lucky. Just when the guild system was being expanded, a periodical named Le Mercure galant (the Gallant Mercury) was being launched in Paris: it covered a wide range of subjects related to the French court and Parisian life. One early reader wrote a letter to its editor, Jean Donneau de Visé, praising the periodical’s “urbanité,” the way it managed to capture the air of high society and the tone of the talk of the town.

Reproduction of the “Ladies in Blue” fresco, Crete, Minoan Greece, Late Bronze Age (c. 1500 BC). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dodge Fund, 1927.

In January 1678, in addition to monthly issues, the periodical began to print special issues, known as extraordinaires, on a quarterly basis. The extraordinaires were the first publication in the periodical press devoted to fashion. It also marked the first time men’s and women’s fashions were discussed together. The Mercure’s coverage contained the earliest fashion illustrations ever published alongside articles discussing the outfits they depicted. Prior to this time, only occasional single prints showing off an individual outfit had circulated.

In Paris in 1678 luxury fashion became news, and contemporary fashion began to be taken seriously enough to be discussed in detail in print. The modern marketing of fashion had begun. The couturières were suddenly front and center in breaking fashion news.

None of this would have developed—not the print coverage, not the illustrations, not the spotlight on female fashion professionals—without the garment that the 1675 statutes made “the exclusive preserve” of couturières: the royal decree called it a robe de chambre, a dressing gown. One-piece dresses with a basic cut in general much like that of a kimono, dressing gowns had arrived in Europe as a byproduct of trade with the Indies. Some early dressing gowns sold in Paris were described as Indian—which could have meant they had been imported from Japan via India, or that they had been created by Indian craftsmen copying Japanese styles.

But the original couturières produced dressing gowns unlike any seen before. They were loosely fitted gowns, loose coat dresses if you will, without stays to limit women’s movement. Worn over a bodice (which usually did contain stays, though readily adjustable ones) and a skirt of either matching or contrasting fabric, much in the spirit of what are now called separates, the casual dress of the 1670s often showed off textiles and trim just as luxurious as those used for court dress. But while robes de cour were designed to be imposing and formal, robes de chambre were easygoing and relaxed. The couturières had transformed the kimono into Western high fashion. Parisiennes took their casual wear—all of it designed by couturières—out into the world, even the world of high society—everywhere, that is, but to court. And on this fashion dichotomy, court versus city, the sector of the modern fashion industry known as couture was founded.

The Mercure galant’s January 1678 quarterly opened with a letter from the editor dedicating it to his female readers on the grounds that “it is all about what you have made yourselves or what you have had others make for you.” Nowhere does this dedication read more clearly than in the section devoted to new trends in high fashion; there, editor Donneau de Visé focused attention on the women who made robes de chambre and on the women who wore them.

One should either be a work of art, or wear a work of art.

—Oscar Wilde, 1894He explained that in Paris, styles had begun to change as quickly as the weather. Henceforth, he predicted, women would begin to follow the latest trends and would update their wardrobes every season. Then began his coverage of the latest fashions by writing off court dress completely: “Since today in France people want to be comfortable, they rarely get formally dressed anymore…Robes are now worn only for ceremonial visits; no one puts them on to visit with their friends or to go out walking.” So what had replaced the tailors’ costly preserve, the robe? “Almost no one today wears anything but what is known as a manteau.” The manteau (“coat” in modern French) was the other name that began to be used in the 1670s to designate the dressing-gown style, the same habits de commodité that the royal statutes had reserved for the couturières.

According to the article, which was reprinted and read throughout Europe, a new age had dawned for couture. Parisian high fashion was now dictated by women—by women designers taking their lead from their clients and producing high-fashion garments suited to the way these women wanted to live. For the first time, luxury fashion aimed to do more than make its clients look wealthy and grand: designers began to take their clients’ lifestyles into account.

The January 1678 extraordinaire included extended coverage of the dressing-gown style, from illustrations to a point-by-point discussion of the details that made the look distinctive. The fashion plates were engraved from drawings by Jean Berain, who had sketched dressed mannequins provided by fashion designers. Berain was none other than Louis XIV’s official designer and chief decorator for the Paris Opera Ballet. His participation in the new project suggests that the king and Colbert had approved the Mercure galant’s initiative, that they were hoping it could increase the economic potential of French fashion.

Like all fashion publications ever since, the special quarterly issue gave designers a prominent role in its pages. It included a section in which the editor described the work of the most important couturières. Donneau de Visé reserved his highest praise for Madame du Creux, whose shop was on the rue Traversine (today’s rue Molière), not far from the Louvre and near some of Paris’ wealthiest neighborhoods. He advised readers that, in order to secure a manteau “made exactly as they are styled for women of the court,” they had to become a client of du Creux, “who dresses the greatest number of women of the highest rank.” Du Creux was an early member of the new guild; in March 1679 her daughter Louise also joined the ranks of maîtresses couturières, making the shop on rue Traversine the first fashion house to be run by two generations of female designers.

“In a Sweat Shop,” by Jacob A. Riis, c. 1890. © The Museum of the City of New York / Art Resource, NY.

Le Mercure galant was once again a harbinger: in the following decades, promotions for individual designers proliferated. The most prominent example occurred in the early 1690s: when Nicolas de Blégny published his best-of guides to Paris, he included sections on both master tailors and mistress seamstresses. Among the couturières he ranked as the finest in the city were Madame Villeneuve, whose shop was situated near the Place des Victoires, and Madame Rémond, on the rue des Petits-Champs—in 1679 Rémond had been chosen by her fellow couturières as one of the fledgling guild’s original officers.

Notices such as these indicate that in France luxury fashion had begun to reach the kind of clientele that had been inconceivable in earlier periods. During all the centuries when tailors’ rule was unchallenged, high-fashion garments had been produced exclusively for courtiers and individuals of the highest rank, clients who showed off their expensive finery in restricted circles and who renewed their wardrobes only infrequently. The style of dress worn at court remained confined to court circles, rather than being copied far and wide.

In order to serve as the springboard for an industry worthy of the name, luxury fashion had to become less high and mighty. A larger segment of the population had to own high-fashion garments, and they had to be encouraged to own more of them than ever before. It is not surprising that French luxury fashion began to be promoted when the couturières came on the scene with their robes de chambre. It was a style likely to encourage more frequent purchases. If women in Paris eagerly adopted the casual style, women elsewhere were likely to follow suit.

Follow they did, and as a result high fashion began to generate an unprecedented volume in sales. The dressing-gown style quickly spread from Paris to the French provinces, and Le Mercure galant reported on its sightings in Strasbourg and elsewhere. It also spread through the ranks of society: soon, as Blégny’s guides attest, shops in Paris sold both secondhand robes de chambre—which purchasers could take to a couturière for alteration—and ready-made ones: the new haute couture had spawned prêt-à-porter.

Between 1681 and 1683, the number of couturières in the fledgling Parisian guild more than doubled, a rapid increase that testified to the manteau’s immediate success. And by 1690 their ranks were 300 strong: there were as many couturières as hat makers or goldsmiths. They were far outnumbered by the tailors’ guild, which had 2,000 members, but it was still a remarkable success story.

The striking new garment they had championed changed the look of French society in many ways. By the late seventeenth century, foreign visitors to Paris frequently remarked that, because every woman in the city seemed to be wearing dressing gowns, it had become hard to distinguish shopgirls from great ladies.

The new look immediately spread beyond French borders, to begin with to England, where it was known as a mantua. (In Italy, where French fashion prints depicting the new style were soon pirated, the manteau was called a manto.) The word mantua first appeared in print in The London Gazette in 1678, the year when Le Mercure galant began promoting it. In 1712 The Spectator informed readers about “the most celebrated mantua makers in Paris.” Before long, the term mantua maker was so popular that it became a synonym for dressmaker. On February 22, 1776, in the opening moments of the American Revolutionary War, The Boston News-let devoted space to publicizing “all the mantua makers in town.” A full century after Le Mercure galant had sung the praises of couturières and their manteaus, female fashion designers were still providing good copy for the periodical press.

In the wake of the Parisian couturières, their English counterparts mounted a successful challenge to tailors’ long monopoly over the production of women’s fashion. By the 1690s, Merchant Tailors in York and other provincial cities were fighting to stop women from making that popular new garment, the mantua. In 1704 the York Merchant Tailors finally admitted a limited form of defeat; they accepted the first woman into their ranks—on the condition that a Mrs. Johnson limit her work strictly to mantuas.

Through the eighteenth century in Paris, the same basic style—a coat dress without stays worn over separates—remained the height of fashion. The train usually found on the earliest models was eliminated early in the century, and the dress then often became known as robe volante, or flying dress: when it was made in newly popular silk or cotton fabrics, the yards of light textile swirled and seemed to fly through the air when women walked. Flying dresses are featured in all the great paintings of the age, such as Antoine Watteau’s celebrated scenes of Parisians at leisure.

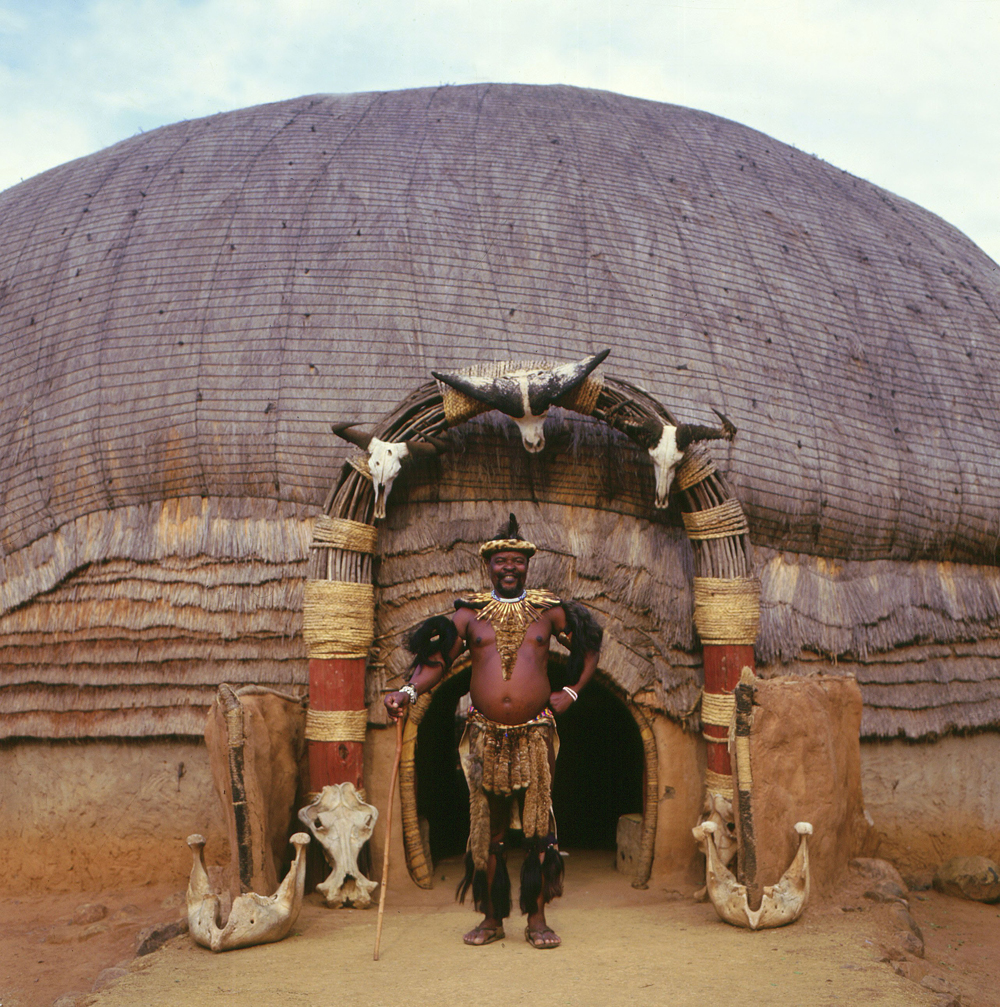

Zulu man standing outside his beehive hut, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Photograph by Stephanie Colasanti. © Stephanie Colasanti / The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY.

The robe met a much harsher fate. Beginning with Louis XIV, every French monarch banned dressing gowns from court and tried to impose official court dress, the tailors’ preserve. But women of the French court were not to be confined. Already in 1686, their revolt began: the wife of the king’s son and heir was having a difficult pregnancy; she complained about the robe’s rigidity. An official decree soon came down: “From now on, Madame la Dauphine will wear only robes de chambre.” And once that door had been opened, it couldn’t easily be shut again. By the 1690s, the Duchesse de Bourgogne—wife of Louis XIV’s grandson, a darling of the aging Sun King, and a young woman famous for her sense of style—was making appearances at court balls, with “the ladies of the court” following after her “in robes de chambre.” And by 1721 the Marquise de Balleroy reported to a friend in the provinces that the women of the French court considered court dress “absolutely useless.”

One should either be a work of art, or wear a work of art.

—Oscar Wilde, 1894In France the guild system was still another casualty of the Revolution: a 1791 law abolished all corporations. Then, in the early nineteenth century, guild systems gradually disappeared all over Europe.

In the postguild world of modern high fashion, women no longer enjoyed official protection of any kind. The couturières quickly lost the status they had enjoyed since 1675. At the same time as they were losing status, the word couturier was becoming magic, with connotations of design genius. And today the feminine form, couturière—such a proud, revolutionary term in the seventeenth century—is reserved for the bottom rung of the vestimentary ladder. Most couturières currently working on French soil toil away in Aubervilliers, the banlieue of Paris that is the center of the illegal textile trade in France.

But the original couturières left a legacy: the manteau.

The manteau, the creation of the combined efforts of female designers and their clients, swept the French court and the Western world and went on to become one of the most influential garments of all time. In fact, as I was putting the finishing touches to these remarks, sitting at a desk only a few hundred yards from the French National Archives, a photo in the International New York Times caught my eye. In it, Pharrell Williams, described by the Times as “a widely embraced icon of casual luxury,” is depicted in a long, loose-fitting coatlike garment—definitely neither outerwear designed for warmth nor a suit jacket. It’s the couturières’ manteau, still going strong 350 years later, still easily adapted for other times and other clienteles.