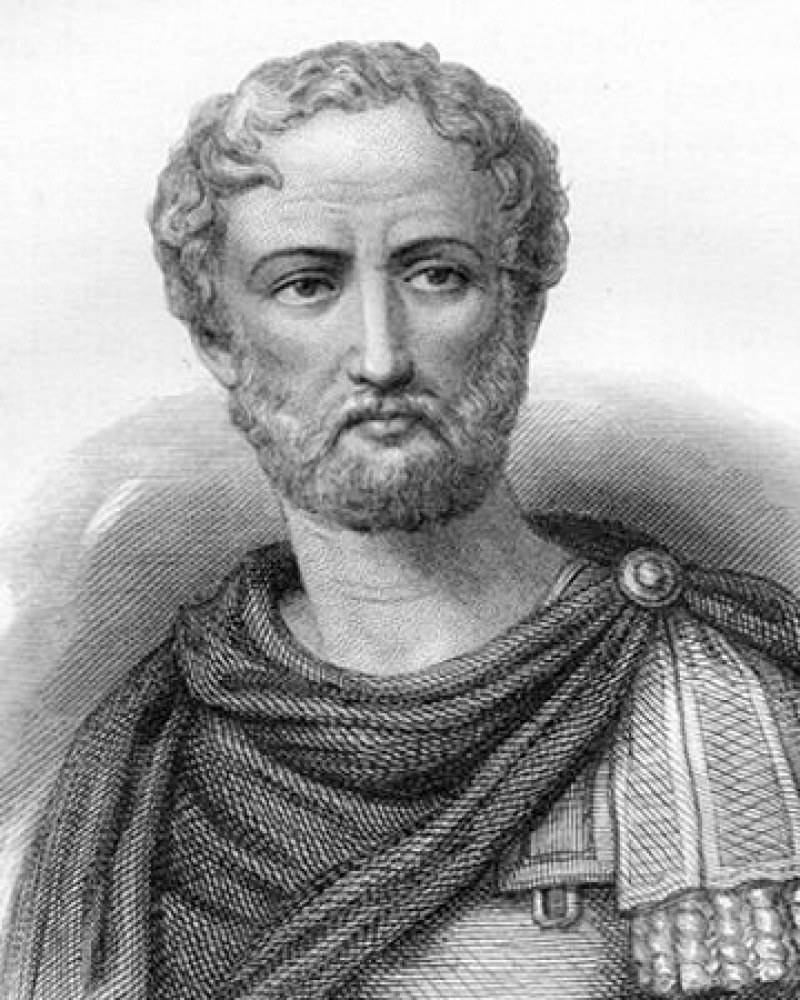

Pliny the Elder

The Natural History,

c. 77

The Natural History,

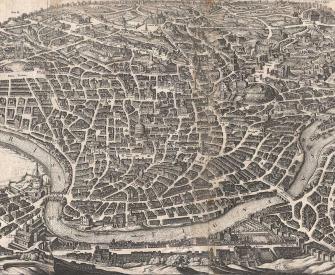

In the days of our ancestors, it was these that were to be seen in their halls, and not statues made by foreign artists, or works in bronze or marble: portraits modelled in wax were arranged, each in its separate niche, to be always in readiness to accompany the funeral processions of the family; occasions on which every member of the family that had ever existed was always present. The pedigree, too, of the individual was traced in lines upon each of these colored portraits. Their muniment rooms, too, were filled with archives and memoirs, stating what each had done when holding the magistracy. On the outside, again, of their houses, and around the thresholds of their doors, were placed other statues of those mighty spirits, in the spoils of the enemy there affixed, memorials which a purchaser even was not allowed to displace—so that the very house continued to triumph even after it had changed its master. A powerful stimulus to emulation this, when the walls each day reproached an unwarlike owner for having thus intruded upon the triumphs of another!