Anyone who doesn’t know foreign languages knows nothing of his own.

—Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, 1821Last Stand

Nicholson Baker tries to stop Wikipedia deletions.

The first thing I did on Wikipedia (under the username Wageless) was to make some not-very-good edits to the page on bovine somatotropin. I clicked the “edit this page” tab, and immediately had an odd, almost lightheaded feeling, as if I had passed through the looking glass and was being allowed to fiddle with some huge engine or delicate piece of biomedical equipment. It seemed much too easy to do damage; you ask, Why don’t the words resist me more? Soon, though, you get used to it. You recall the central Wikipedian directive: “Be Bold.” You start to like life on the inside.

After bovine hormones, I tinkered a little with the plot summary of the article on Sleepless in Seattle, while watching the movie. A little later I made some adjustments to the intro in the article on hydraulic fluid—later still someone pleasingly improved my fixes. After dessert one night, my wife and I looked up recipes for cobbler, and then I worked for a while on the cobbler article, though it still wasn’t right. I did a few things to the article on periodization. About this time I began standing with my computer open on the kitchen counter, staring at my growing watchlist, checking, peeking. I was, after about a week, well on my way to a first-stage Wikipedia dependency.

But the work that really drew me in was trying to save articles from deletion. This became my chosen mission. Here’s how it happened. I read a short article on a post-Beat poet and small-press editor named Richard Denner, who had been a student in Berkeley in the sixties and then, after some lost years, had published many chapbooks on a hand press in the Pacific Northwest. The article was proposed for deletion by a user named PirateMink, who claimed that Denner wasn’t a notable figure, whatever that means. (There are quires, reams, bales of controversy over what constitutes notability in Wikipedia: nobody will ever sort it out.) Another user, Stormbay, agreed with PirateMink: no third-party sources, ergo not notable.

Denner was in serious trouble. I tried to make the article less deletable by incorporating a quote from an interview in the Berkeley Daily Planet—Denner told the reporter that in the sixties he’d tried to be a street poet, “using magic markers to write on napkins at Cafe Med for espressos, on girls’ arms and feet.” (If an article bristles with some quotes from external sources these may, like the bushy hairs on a caterpillar, make it harder to kill.) And I voted “keep” on the deletion-discussion page, pointing out that many poets publish only chapbooks: “What harm does it do to anyone or anything to keep this entry?”

An administrator named Nakon—one of about a thousand peer-nominated volunteer administrators—took a minute to survey the two “delete” votes and my “keep” vote and then killed the article. Denner was gone. Startled, I began sampling the “AfDs” (the Articles for Deletion debate pages) and the even more urgent “speedy deletes” and “PRODs” (proposed deletes) for other items that seemed unjustifiably at risk; when they were, I tried to save them. Taekwang Industry—South Korean textile company—was one. A user named Kusunose had “prodded” it—that is, put a red-edged banner at the top of the article proposing it for deletion within five days. I removed the banner, signaling that I disagreed, and I hastily spruced up the text, noting that the company made “Acelan” brand spandex, raincoats, umbrellas, sodium cyanide, and black abaya fabric. The article didn’t disappear: wow, did that feel good.

So I kept on going. I found press citations and argued for keeping the Jitterbug telephone, a large-keyed cell phone with a soft earpiece for elder callers; and Vladimir Narbut, a minor Russian Acmeist poet whose second book, Halleluia, was confiscated by the police; and Sara Mednick, a San Diego neuroscientist and author of Take a Nap! Change Your Life; and Pyro Boy, a minor celebrity who turns himself into a human firecracker on stage. I took up the cause of the Arifs, a Cyprio-Turkish crime family based in London (on LexisNexis I found that the Irish Daily Mirror called them “Britain’s No. 1 Crime Family”); and Card Football, a pokerlike football-simulation game; and Paul Karason, a suspender-wearing guy whose face turned blue from drinking colloidal silver; and Jim Cara, a guitar restorer and modem-using music collaborationist who badly injured his head in a ski-flying competition; and writer Owen King, son of Stephen King; and Whitley Neill Gin, flavored with South African botanicals; and Whirled News Tonight, a Chicago improv troupe; and Michelle Leonard, a European songwriter, co-writer of a recent glam hit called “Love Songs (They Kill Me).”

All of these people and things had been deemed nonnotable by other editors, sometimes with unthinking harshness—the article on Michelle Leonard was said to contain “total lies.” (Wrongly—as another editor, Bondegezou, more familiar with European pop charts, pointed out.) When I managed to help save something I was quietly thrilled—I walked tall, like Henry Fonda in Twelve Angry Men.

At the same time as I engaged in these tiny, fascinating (to me) “keep” tussles, hundreds of others were going on all over Wikipedia. I signed up for the Article Rescue Squadron, having seen it mentioned in Broughton’s manual: the ARS is a small group that opposes “extremist deletion.” And I found out about a project called WPPDP (for “WikiProject Proposed Deletion Patrolling”) in which people look over the PROD lists for articles that shouldn’t be made to vanish. Since about fifteen hundred articles are deleted a day, this kind of work can easily become life-consuming, but some editors (for instance a patient librarian whose username is DGG) seem to be able to do it steadily week in and week out and stay sane. I, on the other hand, was swept right out to the Isles of Shoals. I stopped hearing what my family was saying to me—for about two weeks I all but disappeared into my screen, trying to salvage brief, sometimes overly promotional but nevertheless worthy biographies by recasting them in neutral language, and by hastily scouring newspaper databases and Google Books for references that would bulk up their notability quotient. I had become an “inclusionist.”

That’s not to say that I thought that every article should be fought for. Someone created an article called Plamen Ognianov Kamenov. In its entirety, the article read: “Hi my name is Plamen Ognianov Kamenov. I am Bulgarian. I am smart.” The article is gone—understandably. Someone else, evidently a child, made up a lovely short tale about a fictional woman named Empress Alamonda, who hated her husband’s chambermaids. “She would get so jealous she would faint,” said the article. “Alamonda died at 6:00 pm in her room. On August 4, 1896.” Alamonda is gone, too.

Still, a lot of good work—verifiable, informative, brain-leapingly strange—is being cast out of this paperless, infinitely expandable accordion folder by people who have a narrow, almost grade-schoolish notion of what sort of curiosity an online encyclopedia will be able to satisfy in the years to come.

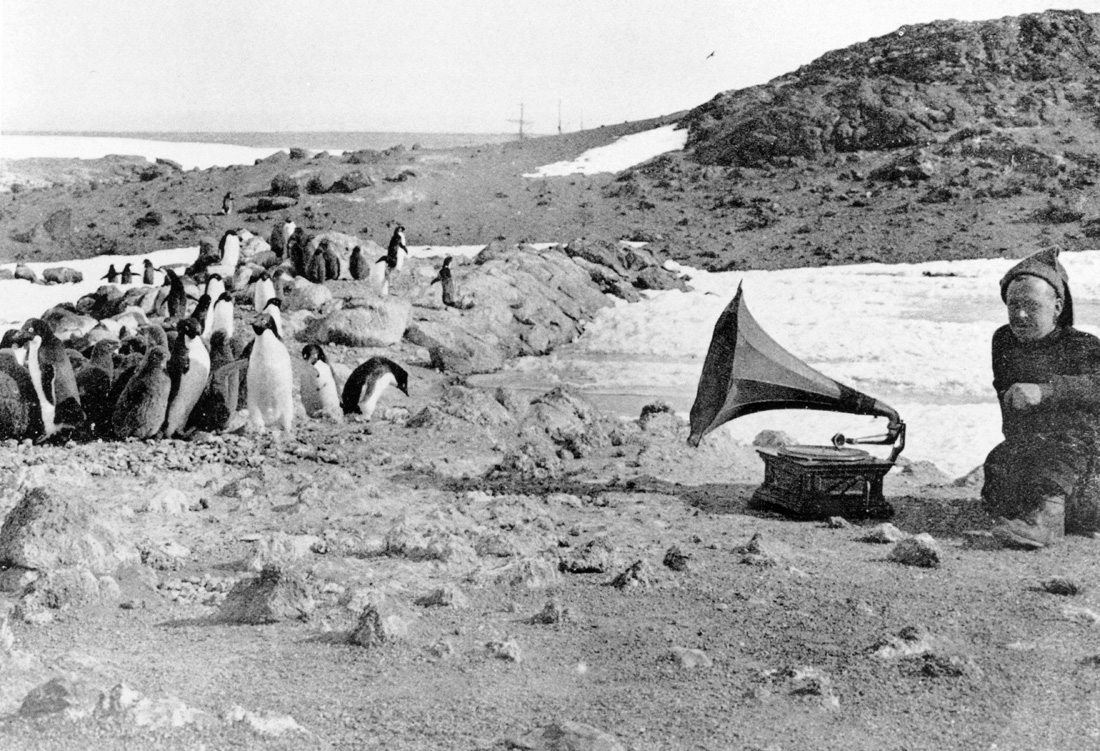

Penguins listening to a gramophone during Ernest Shackleton’s expedition to Anartica, 1907. The Bridgeman Art Library.

Anybody can “pull the trigger” on an article (as Broughton phrases it)—you just insert a double-bracketed software template. It’s harder to improve something that’s already written, or to write something altogether new, especially now that so many of the World Book–sanctioned encyclopedic fruits are long plucked. There are some people on Wikipedia now who are just bullies, who take pleasure in wrecking and mocking peoples’ work—even to the point of laughing at nonstandard “Engrish.” They poke articles full of warnings and citation-needed notes and deletion prods till the topics go away.

In the fall of 2006, groups of editors went around getting rid of articles on web-comic artists—some of the most original and articulate people on the Internet. They would tag an article as nonnotable and then crowd in to vote it down. One openly called it the “web-comic articles purge of 2006.” A victim, Trev-Mun, author of a comic called Ragnarok Wisdom, wrote, “I got the impression that they enjoyed this kind of thing as a kid enjoys kicking down others’ sandcastles.” Another artist, Howard Tayler, said, “‘Notability purges’ are being executed throughout Wikipedia by empire-building, wannabe tin-pot dictators masquerading as humble editors.” Rob Balder, author of a web comic called PartiallyClips, likened the organized deleters to book burners, and he said, “Your words are polite, yeah, but your actions are obscene. Every word in every valid article you’ve destroyed should be converted to profanity and screamed in your face.”

As the deletions and ill-will spread in 2007—deletions not just of web comics but of companies, urban places, websites, lists, people, categories, and ideas—all deemed to be trivial, “NN” (nonnotable), “stubby,” undersourced, or otherwise unencyclopedic—Andrew Lih, one of the most thoughtful observers of Wikipedia’s history, told a Canadian reporter, “The preference now is for excising, deleting, restricting information rather than letting it sit there and grow.” In September 2007, Jimbo Wales, Wikipedia’s panjandrum—himself an inclusionist who believes that if people want an article about every Pokemon character, then hey, let it happen—posted a one-sentence stub about Mzoli’s, a restaurant on the outskirts of Cape Town, South Africa. It was quickly put up for deletion. Others saved it, and after a thunderstorm of vandalism (e.g., the page was replaced with “I hate Wikipedia, it’s a far-left propaganda instrument, some far-left gangs control it”), Mzoli’s is now a model piece, spiky with press citations. There’s even, as of January, an article about “Deletionism and inclusionism in Wikipedia”—it too survived an early attempt to purge it.

© 2008 by Nicholson Baker. First appeared in The New York Review of Books. Used with permission of Melanie Jackson Agency, LLC.

Nicholson Baker

From “The Charms of Wikipedia.” According to the “History of Wikipedia” page on Wikipedia, “The earliest known proposal for an online encyclopedia was made by Rick Gates in 1993, but the concept of an open-source web-based online encyclopedia was proposed by Richard Stallman around 1999. Wikipedia was formally launched on 15 January 2001 by Jimmy Wales and Larry Sanger.” Baker published his first novel, The Mezzanine, in 1988. His most recent book is House of Holes: A Book of Raunch, published in 2011.