The first requisite to happiness is that a man be born in a famous city.

—Euripides, 415 BCBlowing into Town

F. Scott Fitzgerald takes a bite of the Big Apple.

There was first the ferry boat moving softly out from the Jersey shore at dawn—the moment crystallized into my first symbol of New York. Five years later when I was fifteen, I went into the city from school to see Ina Claire in The Quaker Girl and Gertrude Bryan in Little Boy Blue. Confused by my hopeless and melancholy love for them both, I was unable to choose between them—so they blurred into one lovely entity, the girl. She was my second symbol of New York. The ferry boat stood for triumph, the girl for romance. In time I was to achieve some of both, but there was a third symbol that I have lost somewhere, and lost forever.

I found it on a dark April afternoon after five more years.

“Oh, Bunny,” I yelled, “Bunny!”

He did not hear me—my taxi lost him, picked him up again half a block down the street. There were black spots of rain on the sidewalk, and I saw him walking briskly through the crowd wearing a tan raincoat over his inevitable brown getup; I noted with a shock that he was carrying a light cane.

“Bunny!” I called again, and stopped. I was still an undergraduate at Princeton while he had become a New Yorker. This was his afternoon walk, this hurry along with his stick through the gathering rain, and as I was not to meet him for an hour it seemed an intrusion to happen upon him engrossed in his private life. But the taxi kept pace with him, and as I continued to watch I was impressed: he was no longer the shy little scholar of Holder Court—he walked with confidence, wrapped in his thoughts and looking straight ahead, and it was obvious that his new background was entirely sufficient to him. I knew that he had an apartment where he lived with three other men, released now from all undergraduate taboos, but there was something else that was nourishing him, and I got my first impression of that new thing—the metropolitan spirit.

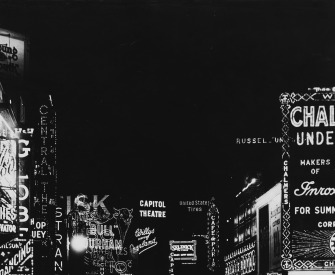

Up to this time I had seen only the New York that offered itself for inspection—I was Dick Whittington up from the country gaping at the trained bears, or a youth of the Midi dazzled by the boulevards of Paris. I had come only to stare at the show, though the designers of the Woolworth Building and the Chariot Race Sign, the producers of musical comedies and problem plays could ask for no more appreciative spectator, for I took the style and glitter of New York even above its own valuation. But I had never accepted any of the practically anonymous invitations to debutante balls that turned up in an undergraduate’s mail, perhaps because I felt that no actuality could live up to my conception of New York’s splendor. Moreover she to whom I fatuously referred as “my girl” was a midwesterner, a fact that kept the warm center of the world out there, so I thought of New York as essentially cynical and heartless—save for one night when she made luminous the Ritz Roof on a brief passage through.

Lately, however, I had definitely lost her and I wanted a man’s world and this sight of Bunny made me see New York as just that. A week before, Monsignor Fay had taken me to the Lafayette where there was spread before us a brilliant flag of food, called an hors d’oeuvre, and with it we drank claret that was as brave as Bunny’s confident cane—but after all it was a restaurant, and afterward we would drive back over a bridge into the hinterland. The New York of undergraduate dissipation, of Bustanoby’s, Shanley’s, Jack’s, had become a horror, and though I returned to it, alas, through many an alcoholic mist, I felt each time a betrayal of a persistent idealism. My participation was prurient rather than licentious, and scarcely one pleasant memory of it remains from those days; as Ernest Hemingway once remarked, the sole purpose of the cabaret is for unattached men to find complaisant women. All the rest is a wasting of time in bad air.

But that night in Bunny’s apartment life was mellow and safe, a finer distillation of all that I had come to love at Princeton. The gentle playing of an oboe mingled with city noises from the street outside, which penetrated into the room with difficulty through great barricades of books; only the crisp tearing open of invitations by one man was a discordant note. I had found a third symbol of New York, and I began wondering about the rent of such apartments and casting about for the appropriate friends to share one with me.

Fat chance—for the next two years I had as much control over my own destiny as a convict over the cut of his clothes. When I got back to New York in 1919, I was so entangled in life that a period of mellow monasticism in Washington Square was not to be dreamed of. The thing was to make enough money in the advertising business to rent a stuffy apartment for two in the Bronx. The girl concerned had never seen New York, but she was wise enough to be rather reluctant. And in a haze of anxiety and unhappiness I passed the four most impressionable months of my life.

New York had all the iridescence of the beginning of the world. The returning troops marched up Fifth Avenue, and girls were instinctively drawn east and north toward them—we were, at last, admittedly the most powerful nation, and there was gala in the air. As I hovered ghostlike in the Plaza Rose Room of a Saturday afternoon, or went to lush and liquid garden parties in the east sixties or tippled with Princetonians in the Biltmore Bar, I was haunted always by my other life—my drab room in the Bronx, my square foot of the subway, my fixation upon the day’s letter from Alabama—would it come and what would it say?—my shabby suits, my poverty and love. While my friends were launching decently into life I had muscled my inadequate bark into midstream. The gilded youth circling around young Constance Bennett in the Club de Vingt, the classmates in the Yale-Princeton Club whooping up our first after-the-war reunion, the atmosphere of the millionaires’ houses that I sometimes frequented—these things were empty for me, though I recognized them as impressive scenery and regretted that I was committed to other romance. The most hilarious luncheon table or the most moony cabaret—it was all the same; from them I returned eagerly to my home on Claremont Avenue—home because there might be a letter waiting outside the door. One by one my great dreams of New York became tainted. The remembered charm of Bunny’s apartment faded with the rest when I interviewed a blowsy landlady in Greenwich Village. She told me I could bring girls to the room, and the idea filled me with dismay. Why should I want to bring girls to my room?—I had a girl. I wandered through the town of 127th Street, resenting its vibrant life, or else I bought cheap theater seats at Gray’s drugstore and tried to lose myself for a few hours in my old passion for Broadway. I was a failure—mediocre at advertising work and unable to get started as a writer. Hating the city, I got roaring, weeping drunk on my last penny and went home.

Incalculable city. What ensued was only one of a thousand success stories of those gaudy days, but it plays a part in my own movie of New York. When I returned six months later, the offices of editors and publishers were open to me, impresarios begged plays, the movies panted for screen material. To my bewilderment I was adopted not as a midwesterner, not even as a detached observer, but as the very archetype of what New York wanted. This statement requires some account of the metropolis in 1920.

There was already the tall white city of today, already the feverish activity of the boom, but there was a general inarticulateness. As much as anyone, the columnist F. P. A. guessed the pulse of the individual and of the crowd, but shyly, as one watching from a window. Society and the native arts had not mingled—Ellin Mackay was not yet married to Irving Berlin. Many of Peter Arno’s people would have been meaningless to the citizen of 1920, and save for F. P. A.’s column there was no forum for metropolitan urbanity.

Blackfoot Indians on the roof of the Hotel McAlpin, on which they pitched teepees to sleep, New York City, 1913. © Newberry Library, Chicago, The Bridgeman Art Library International.

Then, for just a moment, the “younger generation” idea became a fusion of many elements in New York life. People of fifty might pretend there was still a four hundred, or Maxwell Bodenheim might pretend there was a Bohemia worth its paint and pencils—but the blending of the bright, gay, vigorous elements began then, and for the first time there appeared a society a little livelier than the solid mahogany dinner parties of Emily Price Post. If this society produced the cocktail party, it also evolved Park Avenue wit, and for the first time an educated European could envisage a trip to New York as something more amusing than a gold trek into a formalized Australian bush.

For just a moment, before it was demonstrated that I was unable to play the role, I, who knew less of New York than any reporter of six months’ standing and less of its society than any hall-room boy in a Ritz stage line, was pushed into the position not only of spokesman for the time but of the typical product of that same moment. I, or rather it was “we” now, did not know exactly what New York expected of us and found it rather confusing. Within a few months after our embarkation on the metropolitan venture, we scarcely knew anymore who we were, and we hadn’t a notion what we were. A dive into a civic fountain, a casual brush with the law, was enough to get us into the gossip columns, and we were quoted on a variety of subjects we knew nothing about. Actually our “contacts” included half a dozen unmarried college friends and a few new literary acquaintances—I remember a lonesome Christmas when we had not one friend in the city, nor one house we could go to. Finding no nucleus to which we could cling, we became a small nucleus ourselves, and gradually we fitted our disruptive personalities into the contemporary scene of New York. Or rather New York forgot us and let us stay.

This is not an account of the city’s changes but of the changes in this writer’s feeling for the city. From the confusion of the year 1920, I remember riding on top of a taxicab along deserted Fifth Avenue on a hot Sunday night, and a luncheon in the cool Japanese gardens of the Ritz with the wistful Kay Laurell and George Jean Nathan, and writing all night again and again and paying too much for minute apartments and buying magnificent but broken-down cars. The first speakeasies had arrived, the toddle was passé, Montmartre was the smart place to dance, and Lilyan Tashman’s fair hair weaved around the floor among the enliquored college boys. The plays were Déclassée and Sacred and Profane Love, and at the Midnight Frolic you danced elbow to elbow with Marion Davies and perhaps picked out the vivacious Mary Hay in the pony chorus. We thought we were apart from all that; perhaps everyone thinks they are apart from their milieu. We felt like small children in a great bright unexplored barn. Summoned out to Griffith’s studio on Long Island, we trembled in the presence of the familiar faces of the Birth of a Nation; later I realized that behind much of the entertainment that the city poured forth into the nation there were only a lot of lost and lonely people. The world of the picture actors was like our own in that it was in New York and not of it. It had little sense of itself, and no center: when I first met Dorothy Gish I had the feeling that we were both standing on the North Pole and it was snowing. Since then they have found a home, but it was not destined to be New York.

When bored, we took our city with a Huysmans-like perversity. An afternoon alone in our “apartment” eating olive sandwiches and drinking a quart of Bushmill’s whisky presented by Zoë Akins, then out into the freshly bewitched city, through strange doors into strange apartments with intermittent swings along in taxis through the soft nights. At last we were one with New York, pulling it after us through every portal. Even now I go into many flats with the sense that I have been there before or in the one above or below—was it the night I tried to disrobe in the Scandals, or the night when (as I read with astonishment in the paper next morning) “Fitzgerald Knocks Officer This Side of Paradise”? Successful scrapping not being among my accomplishments, I tried in vain to reconstruct the sequence of events that led up to this denouement in Webster Hall. And lastly from that period I remember riding in a taxi one afternoon between very tall buildings under a mauve and rosy sky; I began to bawl because I had everything I wanted and knew I would never be so happy again.

© 1945 by New Directions Corp, renewed 1972 by Frances Scott Fitzgerald Smith. Used with permission of Harold Ober Associates.

F. Scott Fitzgerald

From “My Lost City.” Called by Ring Lardner the prince and princess of their generation, Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda moved in 1924 to the Riviera, joining an expatriate scene he later described in Tender Is the Night. After Zelda suffered two mental collapses and his drinking increased, he observed in 1936, “Of course all life is a process of breaking down.” He died in Hollywood at the age of forty-four.